Last week, we took a first look at how government fits into the circular flow of income between firms and households, focusing on spending and taxing. This week we’ll look at government borrowing and repayment.

As a reminder, here are the main interactions between a government and the rest of the world. It:

Buys goods and services

Provides public services (e.g. schooling, hospital services, use of public roads)

Makes benefit payments (e.g. pension, unemployment)

Imposes taxes

Collects taxes

Issues “bonds” in exchange for money (borrowing)

Pays bondholders when the bonds mature (repayment)

Pays interest to bondholders

Borrows from the central bank

Repays the central bank

Receives profits from the central bank

We’ve dealt with numbers 1-5. This week we’ll look at 6-11.

Bonds

A bond is just an IOU, or a small collection of IOUs. The main one (called the principal), is an IOU for the amount borrowed, which has a maturity date: the date when it will be paid. For bonds with a maturity date measured in years (rather than weeks) after the bond is issued, there are generally a set of smaller IOUs (called coupons) for interest payments, often paid at 6-month intervals. Before finance was digitised, bonds were mostly pieces of paper, and the coupons were simply strips at the bottom of the bond which could be torn off where the paper was perforated, and presented to the bond issuer for payment of the interest.

Short term bonds (known as bills) don’t have coupons. Instead, the lender pays a little less for the bond than the amount which is paid back (e.g. a bill which pays £1,000 in 6 months could perhaps be bought for £990).

Why do governments borrow?

If you ask different economists why governments borrow, you’ll get some very different answers. Some will say that a government borrows so that it can spend more money than it has already received in taxes. Others, notably those associated with MMT1, will say that a government doesn’t need to borrow in order to spend because a government actually creates new money when it spends, and that borrowing is just a way to reduce the amount of money in circulation, in order to keep inflation from getting too high.

These are really just different perspectives, rather than a fundamental disagreement. MMT’s perspective comes from counting the central bank as part of the government. So as far as MMT is concerned, if the government borrows from the central bank, it’s just accounting internal to “government”, and spending the money is the “government” creating a new debt to the private sector2.

Sources of borrowing

There are basically two main places where the government can go to borrow. The first is the private sector: households, firms and banks. The second is the central bank, which issues currency.3 When the government borrows from the private sector, it’s obtaining existing money, and promising to pay it back later. When it borrows from the central bank, the central bank creates new money, and the government promises to pay it back to the central bank later.

If you’ve been following this substack for a while, you won’t find any surprises in any of the diagrams of interactions between government and the rest of the world.

Government borrowing illustrations

As before, these examples will involve the UK government and the Bank of England (“BoE”). I’ve not read of any significant differences elsewhere, but please let me know in the comments if you’re aware of any.

Do study each one carefully, noting how each sector’s raw net worth4 changes (add up the arrows pointing to the sector, and take away the arrows pointing away).

Issuing bonds

The government creates a new debt to the lender in exchange for the lender transferring some money to the government (via their bank and the BoE).

Notice that the new bond is a new debt for more than the amount the lender paid: the bond includes £200 of coupons in addition to the main £1,000 debt. (This could be a 5-year bond paying 4% interest per year).

So the government’s RNW decreases by £200, and the NBPS’s increases by £200. (The NBPS is being compensated for delaying buying £1,000 of goods/services).

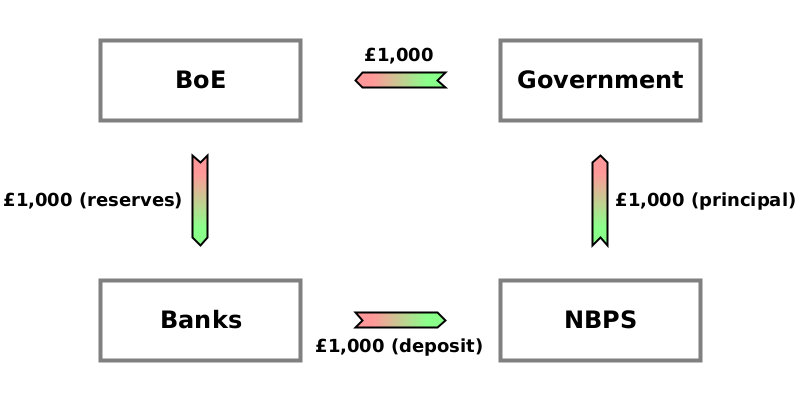

Repaying bonds

The government transfers some money to the bondholder in exchange for the bondholder writing off the debt.

This is just repayment of the principal, so the amount paid is equal to the amount written off.

Nobody’s RNW changes. This is just the government paying what it promised.

Paying interest to bondholders

The government transfers some money to the person presenting a coupon, who agrees to write off the coupon debt in exchange.

Notice that this is exactly the same as repaying the principal. Nobody’s RNW changes. This is again just the government paying what it promised.

Borrowing from the central bank

This is just like any other lending. The government creates a new debt to the BoE in exchange for the BoE creating a new debt to it.

Nobody’s RNW changes as a result of this action. For the changes to each sector’s RNW from the spending which is likely to follow, see last week’s article.

Repaying the central bank

Again, this is just like any other repayment of a loan. The government writes off the debt owed to it by the BoE in exchange for the BoE writing off the debt owed to it by the government.

Nobody’s RNW changes as a result of the government repaying a loan.

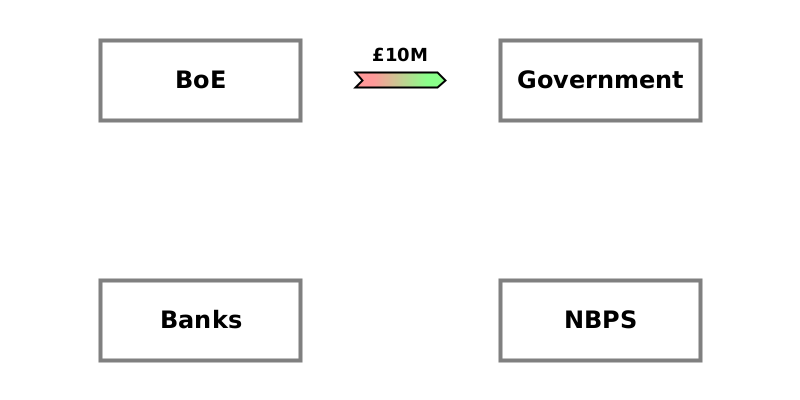

Receiving central bank profits

This is simply a transfer from the BoE to the government, achieved by the BoE adding to the government’s bank balance.

This increases the government’s RNW by £10,000,000 and decreases the Bank of England’s by the same £10,000,000.

(Alternatively, you could think of the relationship as the government having equity in the Bank of England: that the equity increases as soon as the Bank of England makes a profit, and here the Bank of England adds to the government’s account balance in exchange for the government accepting a reduction in its equity, in exactly the same way as we’ve seen equity working before. In practice, there’s no difference between the perspectives).

Summary

All of these interactions between the government and the rest of the world are simple and intuitive. None of this should be controversial to anyone from any school of economics. The only argument to be had is over the interpretation of what is happening, and I am confident that the analysis of how each person’s (or sector’s) RNW changes is key to settling these disputes.

Modern Monetary Theory, championed by Warren Mosler, Stephanie Kelton and L. Randall Wray.

Everyone apart from the government and the central bank.

Governments can also borrow from other nations, known as the foreign sector.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.