Introduction and Plan of the Work

In 1946, Henry Hazlitt—American journalist and author—wrote a book called Economics in One Lesson. It was aimed at the general public, and his stated aim was to protect them against groups with selfish interests who would try to confuse them into accepting government policies which benefited those groups at the expense of everyone else.

Like his book Economics in One Lesson, this substack starts by stating a single lesson, which is then applied to a variety of questions in economics.

Hazlitt’s one lesson was:

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.

This is a good lesson, but it’s hard to apply because “tracing the consequences of a policy” involves predicting the future. Even if the prediction is correct, some people will continue to find plausible-sounding arguments against it.

By an unexpected series of events, I have discovered a new One Lesson which can be used for the same purpose, but which doesn’t involve any speculation about the future. People who understand the simple lesson can immediately see when one group’s benefit comes at the expense of everyone else.

This new one lesson is:

“Raw net worth” might sound like it’s going to be difficult to understand, but it’s just what someone owns, plus what they’re owed, minus what they owe. The ideas should be familiar to people from their everyday experience.

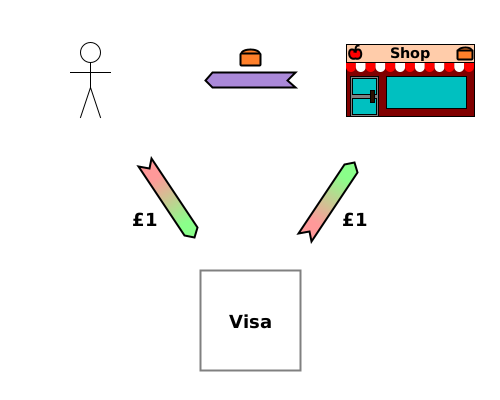

This substack begins with a short series of posts on exactly what RNW is, how someone’s RNW changes, and what effects (if any) that has on everyone else. It also explains some useful diagrams which make economics easy to understand (see below), because it’s so close to people’s intuition. From then on, it’s all about applying this new One Lesson to a series of different questions, and showing how easy the answers are when you use this idea.

I very much hope that this helps to clear away the confusion around economics, and lets you see when you’re being had.

Though Henry Hazlitt was a sharp thinker and had a lot of good things to say about real economic problems, don't forget that he believed banks lend money other people deposited with them.

He ambiguously said in his, Economics in One Lesson, "All credit is debt", and see how he struggled with the ambiguous nature of the word: "There is a strange idea abroad, held by all monetary cranks, that credit is something a banker gives to a man. Credit, on the contrary, is something a man already has. He has it, perhaps, because he already has marketable assets of a greater cash value than the loan for which he is asking. Or he has it because his character and past record have earned it. He brings it into the bank with him. That is why the banker makes him the loan."

Brilliant as that quote is, it contains a vital error, and I find it much easier to stick with strict accounting terminology. To paraphrase the Bank of England's Monetary Analysis Directorate, Credit is a bank liability and liabilities can't be lent out, like assets.