Central Banks

What they do

Before adding a government sector to the circular flow model, it’s worth looking at how central banks work.

A central bank holds accounts for other banks (including foreign central banks) and the national government. The money in these accounts has a special name: reserves, but like deposits in an ordinary bank account, they’re just debts owed by the central bank to the account holder. One account holder can pay another by asking the central bank to transfer some reserves between their accounts.

Here are the other main interactions of a central bank with the rest of the world. There are quite a lot, but they’re all pretty simple. It:

Lends (new) reserves to account holders.

Accepts repayments of loans from account holders.

Allows withdrawals: an account holder swaps reserves for banknotes.

Accepts deposits: an account holder swaps banknotes for reserves.

Buys assets (e.g. government bonds): the seller is given new reserves in exchange1.

Sells assets: the buyer gives up reserves in exchange2.

Receives interest from borrowers.

Pays interest to account holders.

Receives interest on assets.

Writes off a debt if a debtor defaults.

Remits profits to the government.

These are very similar operations to a normal bank. The difference is that, while a normal bank’s main aim may be to make a profit for its shareholders, a central bank may be performing these operations in order to achieve some policy goal, perhaps set by government. But as always, our main focus is on how the operations actually affect each person’s raw net worth3, not what they are attempting to achieve4.

Since I’m from the UK, I’ll use the Bank of England as the example. Other central banks appear to work in a similar way.

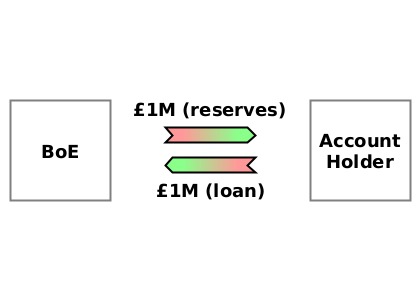

Lending

The account holder (government or bank) or borrows from the Bank of England. This is the usual swap of new debts which we’ve seen from other banks.

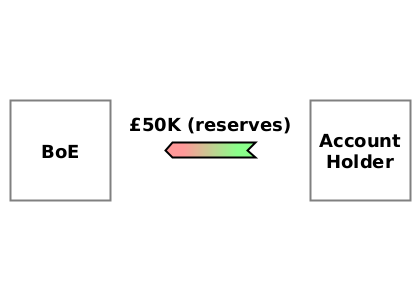

Repayment

The account holder writes off reserves in exchange for the Bank of England agreeing the debt is no longer owed.

Withdrawal

This could be a bank wanting to fill up some of its ATMs. It writes off the reserves, and receives a delivery of banknotes.

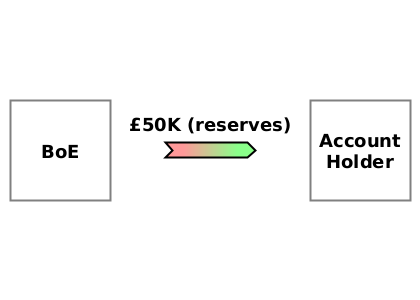

Deposit

If a bank has too much cash, or some of the banknotes are worn, it can deliver them to the Bank of England and receive reserves instead.

Asset purchase

The Bank of England buys a bond from the seller. To pay, it creates new reserves for the seller’s bank, on condition that the bank creates new deposits for the seller.

Asset sale

The Bank of England sells a bond to a buyer, who pays indirectly through their bank.

Receive interest

The Bank of England receives interest on a loan.

Pay interest

The Bank of England may pay interest on reserves held in an account.

Receive interest on assets

If the Bank of England has bought a bond, it receives interest payments from it.

Write off defaulted debt

If a borrower were to default, the Bank of England would have to write off the debt at a loss.

Remit profits

If the Bank of England makes a profit, it passes this to the government by creating new reserves in its account.

Summary

The actual actions of a central bank are effectively the same as any other bank. It is mostly lending or buying assets, which it does by creating new debts (‘reserves’). It charges interest on loans, and may pay interest on reserves. Only interest, defaults and buying and selling assets affect the central bank’s RNW.

If the seller doesn’t have an account with the central bank, payment is indirect: the central bank creates reserves for the seller’s bank, which itself creates a deposit for the seller.

If the buyer doesn’t have an account with the central bank, payment is indirect: the buyer writes off deposits with their bank, which itself writes off reserves with the central bank.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.

Or say they are attempting to achieve.