Creating Money: A Free Lunch?

Does being able to create money make you better off?

Per Bylund is a professor of entrepreneurship at Oklahoma State University, and has recently written an excellent introduction to economics from an “Austrian school” perspective. It is fairly quick to read, and I can highly recommend it.

The Austrian school is a group of economists whose line of thinking was developed by Carl Menger, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, Ludvig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek and a few others. Henry Hazlitt, whose book “Economics in One Lesson” was an inspiration for this substack, was also closely associated with the Austrian school. I’m not an expert on Austrian economics, but what I have read of it seems highly compatible with the One Lesson. Both agree on some key points:

Subjective value: Value isn’t a property of an object itself. It’s up to individuals to determine how valuable a product is to them, and this will be different for different individuals.

There is no such thing as a free lunch.

But there’s a glaring area of disagreement. The Austrian school is strongly opposed to the credit banking system which we saw earlier. It considers all money creation by banks to be inflationary.

This brings us back to Per Bylund, who this week tweeted the following:

We’ve already seen the One Lesson showing us what it means for a bank to create (“print”) new money: the bank creates a new debt (called a “deposit”) owed to someone else. This often happens when it makes a loan, but a bank also creates deposits when it pays employees or suppliers, buys financial assets (such as government bonds), or pays dividends to its owners. Most of these situations involve more than one action: for example, lending involves (1) a bank creating a new deposit for the borrower, in exchange for (2) the borrower creating a new debt (called a “loan”) owed to the bank.

Let’s just focus on the action in which the new money is created.

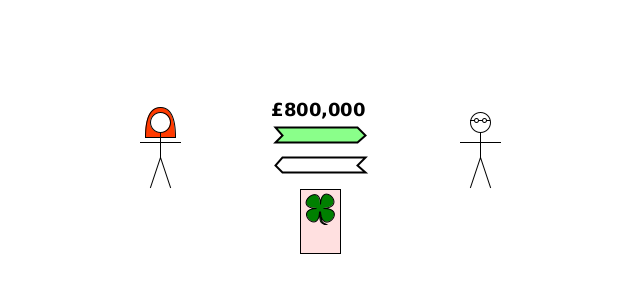

What does it do to the raw net worth1 of a bank when it creates new money? We can see straight away from how the arrow points away from the bank that creating money decreases the RNW of the bank and increases Alice’s RNW. Writing new IOUs is definitely not a get-rich-quick scheme!

Why don’t Austrian economists like money creation?

There is a potential problem with banks creating new money. If it makes them insolvent, it means that there are IOUs circulating in the economy which can’t be paid. Until the bank works its way out of insolvency (by making profits), or goes through bankruptcy (where some of the creditors are forced to write off the debts owed to them), it’s like a game of musical chairs where the players represent the creditors and the chairs represent the bank’s assets. The last creditor to demand payment from the bank, who thought they had valuable money because their bank statement told them so, finds out that the deposit they’d received earlier was just a fake promise all along.

Imagine a bank keeps making more and more bad loans, where the borrowers default. The ratio of creditors to assets gets constantly worse, and so on average, each creditor gets less for their deposit. This should be easier to understand with an example.

Eve starts a new bank, and doesn’t get rich

Eve has no liabilities and her only asset is £1 million of cash, so her RNW is £1 million. She decides to start operating as a bank, lending Alice £800,000, and Bob £500,000. This is fine so far, because both of these are an exchange of RNW: deposit for loan.

Alice then buys £800,000 of lottery tickets from Dom, and loses on all of them.

She now goes through bankruptcy, and Eve is forced to write off the debt.

Eve has lost £800,000 of her RNW, leaving her with £200,000. She is still solvent. But now suppose Bob buys £500,000 of lottery tickets from Dom and loses it all too.

Bob defaults too.

Now Eve’s RNW is negative: -£300,000. She owes £1,300,000 (to Dom), but only has £1,000,000 in assets. Dom will only get 10/13 (~77%) of the amount Eve owes him.

In desperation, Eve lends £400,000 to Charlotte, and charges 100% interest, in the hope of becoming solvent again.

Can you guess what Charlotte does?

Now Eve’s RNW is -£700,000. She owes £1,700,000, but still only has £1,000,000 in assets. So Dom will now only get 10/17 (~59%) of the amount Eve owes him.

Each time Eve makes a bad loan to an incompetent/unlucky gambler from now on, Dom will get a smaller share of what she owes him.

There is always a danger with a bank printing money (or indeed with anyone writing an IOU) that it will become insolvent, and the creditors won’t get what they were promised. That’s certainly a big problem (and it’s the reason banks are generally supposed to have plenty of capital to absorb these losses, like Eve’s original £1 million). But are Austrian economists right to conclude that there’s something wrong with all money printing?

Notice something very important. After Alice defaulted on her massive £800,000 loan, Dom was still able to collect the full amount owed to him by Eve. It was only once Eve became insolvent (because Bob defaulted too) that the money which she created turned out to be a promise which she couldn’t keep. (Charlotte’s default then made things worse).

So I have to conclude that it’s money issuers becoming insolvent that’s the problem, not all creation of new money.

I think I understand why Austrian economists have decided that all money creation is wrong, but that needs a whole post of its own, maybe even a series.

The most important thing to understand is that printing money in the form of new debts isn’t a route to riches for the money printer.

And by the way, I do recommend checking out what Per Bylund has to say on X/Twitter.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe.

I think your arrow notation is inspired by my two favourite renegades, Prof. Richard Werner and Steve Keen, economists who use double-entry accounting rules to explain economic and banking realities. It not only exposes economic fallacies but should also help non-accountants master the confusing logic of double-entry accounting, the in-house language of banking.

But here, tacking “bank jargon” (which you said you “don’t much like” [“Money and Banking (2)”]) onto you arrows misrepresents what banks actually do and disguises the accounting fraud in their “credit-lending” scam. You’ve hidden the bank’s accounting under a layer of misleading “bank jargon” which contradicts what your arrows imply. As you’ve said elsewhere, the “reality” is NOT a “loan” from the bank to Alice but the swapping of equal promises-to-pay (or equal liabilities). Your arrows are correct but their bank-inspired labels are spurious and misleading.

The bank is deceiving Alice, who didn’t give a “loan” to the bank [as the label “£10,000 (loan)” implies] and it didn’t give Alice a “deposit” [as the label “£10,000 (deposit)” implies]. It was Alice who made a “deposit” into the bank; the “exchange value” of her deposit [£10,000.00] was recorded as a “£10,000.00 DR” in Alice’s “debit account” [as a bank asset], and accounting rules forced the bank to record a matching “£10,000.00 CR” in her “credit account” [as a matching bank liability].

Your articles and replies to comments convince me that you understand these facts, but the ambiguity of your “bank jargon” can only mislead readers who don’t. Even worse, such bank jargon sustains the fiasco which allows banks to create the appearance of “a loan” of something [a credit balance] which, according to the Bank of England, “can’t be lent” BECAUSE it’s a bank *liability*.

What Alice has created for herself is a £10,000 “credit facility”. It consists of a “£10,000 debit balance in one account” and a “£10,000 credit balance in another account”. Both balances arose simultaneously when Alice deposited her “promise-to-pay £10,000”. The bank created her two accounts and will do the bookkeeping when she operates the facility, but is otherwise merely a professional “service-provider”, as no “money” is involved, only recording “credits" and "debits”.

Provided Alice agrees it’s strictly a “credit” facility (meaning cash withdrawals are prohibited!), then no bank asset will be put at risk by accepting Alice’s promise-to-pay £10,000. Interest charges and mortgage/security are unjustified for such a “risk free” transaction, viz., swapping Alice’s £10,000 liability for an equal £10,000 bank liability. Her facility should attract legitimate fees for the bank’s “professional accounting services” only.

While any of Alice’s initial £10,000 credit balance remains in circulation, the bookkeeping bank retains a record of that outstanding amount as a “debit balance” in her liability account [i.e., the bank’s asset a/c], which means on-going “account-keeping fees”. Stopping those account-keeping fees is the financial incentive for Alice to pay that "£10,000.00 DR" balance down to £0.00 as quickly as she can, but keeping the facility open should be at her discretion.