Different Types of Consumption?

Reproductive v. Unproductive Consumption

Before finishing the series on income, we need to understand the difference between “reproductive” consumption and “unproductive” consumption. One of them affects income and the other doesn’t. These two terms were used by1 Jean-Baptiste Say, a French economist from the early 19th century who worked in both government and industry. (He’s also my favourite economist!)

A warning for anyone who doesn’t like ambiguity: it’s not always obvious which category a given example of consumption belongs to. But fortunately, the difference doesn’t affect our understanding of what’s happening — it’s only about how we describe it.

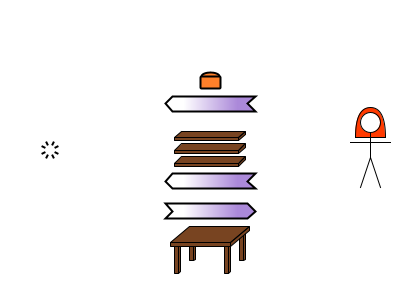

What the two types of consumption have in common is that… they’re both consumption. We represent this with a purple-to-white arrow pointing from the consumer to a “void” symbol, showing that it decreases the consumer’s raw net worth2 without increasing anyone else’s, by using up a tangible asset which they own.

The difference between the two types isn’t what you’re consuming, or when, but why you’re doing it. Specifically, are you consuming for the personal benefit which you get from it, or are you consuming in order to produce something else?

Here’s an example which should help to explain it. You can burn methane (natural gas), and when you do that you’re consuming it. If you’re burning it in a boiler (aka furnace) because you want your house to be a more comfortable temperature, that’s “unproductive” consumption. If you’re burning it in an oven in order to bake bread, that’s “reproductive” consumption, because you’re doing it to produce something else.

“Unproductive” doesn’t mean “useless”. There’s nothing inherently bad about unproductive consumption — people need to consume things just to survive, and consumption often improves people’s standard of living. It’s just that doing so is guaranteed to decrease your RNW. Reproductive consumption in itself also decreases your RNW, but there’s a compensating increase in your RNW from the associated production — hopefully leaving you more satisfied at the end than you were before your reproductive consumption.

Effect on income

Unproductive consumption doesn’t affect your income. Your earlier income left you with a tangible asset of some sort, and you’re deciding to consume it for the personal benefit which you gain as a result.

But reproductive consumption is negative income. It might not be clear what this means, so imagine that one month you’ve worked for an employer and been paid £1,000. You then spend £1 on a 500g bag of flour.

At that point, your income over the month is:

+ £999 + 500g flour

Now imagine you consume the 500g of flour when making a loaf of bread.

Your income is now:

+ £999 + loaf

The 500g flour was subtracted from your income (cancelling out the earlier increase) because otherwise we’re double-counting the benefit which the flour provides. To see why, imagine we didn’t subtract the flour from your income. Then your income would appear to be:

+ £999 + loaf + 500g flour (?!)

It looks as though you’ve received the benefits of having a loaf and the flour. But someone who had an income of both a loaf and flour could eat the bread and, say, make some playdough. That’s not what’s happening here — the flour was used up to make the bread. You get one or the other, not both.

So reproductive consumption is negative income, and unproductive consumption doesn’t affect income.

A problem with GDP

This idea of reproductive consumption being treated differently from unproductive consumption isn’t unique to the One Lesson. Say wrote3 that reproductive consumption is about creating value (by producing something more valuable than was reproductively consumed4), and unproductive consumption is destroying value, although it’s usually for “procuring an enjoyment”.

And if you look at how gross domestic product (GDP) is measured, you’ll see it only counts the production of “finished” (aka “final”) goods and services — that is products which are expected to be sold to people who will consume them unproductively. Flour sold by a miller to a baker isn’t counted as part of GDP: it’s called an “intermediate” good, because it’s expected to be consumed reproductively.

Interestingly, this actually shows up a weakness in how GDP is measured. Suppose Bob buys a bag of flour at a supermarket, and uses it to bake a loaf of bread. The flour is considered a final good, because it was sold to a “consumer” by a shop, so it’s counted as part of GDP. But the bread isn’t. It should really be the other way around, because the flour is consumed reproductively in order to produce the bread, which is the real final product5.

The important point is that some production occurs in households, and so GDP doesn’t represent all production.

This is widely acknowledged as a weakness of GDP measurement, but I believe the bigger danger is that it’s usually not recognised as a weakness of economic theory. If economists assume that essentially all production always occurs in firms, they may draw incorrect conclusions about how best to manage the economy in unusual times. Authorities such as governments and central banks may simply apply the recommendations of academic economists based on their conclusions without even realising that those conclusions could be invalid because of a wrong assumption in their models.

The ambiguity

To finish with, let’s look at how it might be difficult to work out whether consumption is unproductive or reproductive.

One possible example of unproductive consumption could be Alice the carpenter eating bread. But could it be reproductive consumption? Making tables is physical work, so Alice needs energy to do it, and that means eating food. So we could think of eating the bread as a necessary part of making tables, and say it’s actually reproductive consumption.

It’s a matter of judgement whether we count consumption as reproductive or unproductive. If we’re thinking of Alice eating bread as being a part of the production process because it gives her the energy she needs for doing the physical work of making tables, we’re counting it as reproductive consumption. But if we’re thinking of her eating bread so that she doesn’t have to feel hungry while she works, we’re counting it as unproductive consumption.

In the end, it doesn’t matter too much. We can either say:

Alice’s bread consumption is reproductive — eating it is a necessary part of producing the table. In this case, her income is lower6 (because reproductive consumption decreases her income), and her unproductive consumption is lower. Or,

Alice’s bread consumption is unproductive — eating it isn’t necessary for making the table, because she has the option of being hungry. In this case, her income is higher (because unproductive consumption doesn’t decrease her income), and her unproductive consumption is higher.

Either way, the bread is gone and the table is made. The difference is only over how essential we think it is for Alice to eat the bread in order to make the table.

Summary

There are two categories of consumption, and they have different effects on the consumer’s income:

Unproductive consumption is using up a tangible asset for the personal benefit of the consumer. It doesn’t affect the consumer’s income: it’s just using up some of the stock which they obtained from their earlier income.

Reproductive consumption is using up a tangible asset in order to produce another tangible asset — typically one which the consumer would rather have. Because the consumption isn’t for the direct benefit of the consumer, but just to produce something else, this is negative for the consumer’s income. (When they originally gained the tangible asset, that was positive income, so this negative income from the reproductive consumption just undoes it).

With the distinction between the two types of consumption in mind, next time we can come up with a definition of income which should work in all cases.

I haven’t studied the history of economic thought enough to know whether he devised the terms himself. X’s Grok AI says that he did, but that they are a development of some earlier ideas of the French “physiocrat” economists and of Adam Smith, author of The Wealth of Nations.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe (i.e. their assets minus their liabilities). It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them. If the idea is new to you, this article explains it with examples.

Unfortunately, the links from the top of the page to the different sections are broken, so search forward for section 6: “On the Formation of Capital”.

Many governments charge a “value added tax” i.e. a tax of a certain percentage of the difference in “value” between what was produced and what was reproductively consumed in the process.

Unless you use the bread to make a sandwich, etc., in which case that is the final product.

That is, lower than it would be if we called it unproductive consumption.

![[Unproductive] (C) Bob→void {methane}. [Reproductive] (C) Bob→void {methane}; (P) Bob→void {bread}. [Unproductive] (C) Bob→void {methane}. [Reproductive] (C) Bob→void {methane}; (P) Bob→void {bread}.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Sm1w!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff6e2082d-2971-4495-be6a-c1e59639617a_800x200.png)

![[1] (S) Bob→Alice {work}; (TD) Alice→Bob {£1,000}. [2] (TD) Bob→Shop {£1}; (TT) Shop→Bob {flour}. [1] (S) Bob→Alice {work}; (TD) Alice→Bob {£1,000}. [2] (TD) Bob→Shop {£1}; (TT) Shop→Bob {flour}.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!NEMP!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa60a5fbc-8e5b-43eb-aa73-6a73d229d234_800x200.png)

That's such an interesting read. You very succinctly pointed out the problem with using GDP to measure the strength of an economy.