Income (1)

Getting to a reliable and useful definition

If you ask an average person what “income” means, you’ll probably get an answer like, “it’s how much money people get paid for working, and it’s how they can afford to buy things”. Some might even add that interest on savings, and “returns” on investments are also part of a person’s income. That’s a reasonable starting point, especially for employees, but if we’re going to understand the idea really clearly, we need something a bit better. For example, although we’ll start off thinking about money, we’ll see that there’s more to it than that.

In this short series, we’re going to work towards finding a precise meaning of income which is useful for understanding economics, so we can answer questions like:

What exactly do we mean by income?

What units is income measured in?

Which events or actions affect someone’s income?

What’s the economic significance of income?

Is someone’s income always a result of someone else’s spending?

What, if anything, does income mean when we’re looking at Robinson Crusoe on his desert island, where there’s no money?

Is it only real people who have incomes, or do corporations (e.g. limited companies and governments) have incomes too?

If we add up everyone’s income, does that tell us anything interesting?

It’s critically important to get this right. If politicians, government employees and central bankers have a wrong understanding, they can make terrible (as in civilisation-destroying) mistakes1.

Income is a Flow

The first thing to understand about income is that it’s a flow: something which you measure over a period of time, unlike a stock, which is something you measure at a point in time. So it makes sense to ask what Alice’s income was for the whole of 2024, but not what it was at 10:00:00 on 12th December 2024.

A flow in economics works just like a flow of water. Imagine a bath with water in it. The amount of water in the bath stays the same unless water flows in or out. Turning on the tap makes water flow in, increasing the amount of water in the bath. And pulling out the plug makes water flow out, decreasing the amount of water in the bath.

If a bath starts off with 100l of water in it, and pulling out the plug makes it drain at 30l/minute, then after 3 minutes the bath will have 10l remaining. If you put the plug back in, and turn on the tap so that it fills at 10l/minute, then after 3 minutes, the bath will have 40l. If you then leave the tap on but pull out the plug again, the amount of water in the bath will decrease by 20l/minute (30-10 = 20), so 1 minute later the bath will have 20l, and after another minute it will be empty.

In the same way, if someone has a flow of money coming in (e.g. because they are being paid to work), it increases the stock of money which they have. And if they have a flow of money going out (e.g. because they are spending it), it decreases their stock of money. It’s normal for there to be both at the same time, and like the bath, the difference between the inflow and the outflow is how quickly their stock of money is increasing (or decreasing if the outflow is higher).

In the diagram above, Bob’s stock of money increases by £2,000 (£3,000 - £1,000) over the month.

Income for an employee

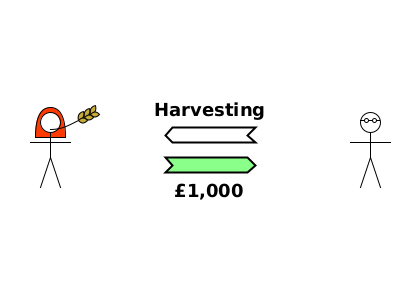

The simplest example of income is for an employee. They do some work for an employer, and the employer pays them some money. This payment of money is their income. Here’s a diagram showing Alice, a farmer, employing Dom to help her to harvest wheat in August:

Dom’s income for August is £1,000.

In the late 18th century, the UK government introduced a “temporary” income tax to fund a war against post-revolutionary France2. The USA introduced a federal income tax in 1913. Once an income tax is in place, whenever someone is paid for their work, some of that money is transferred to the government instead of the employee. Here’s an example:

In the picture above, Bob, who owns a corner shop, employs Charlotte to manage it: putting deliveries of goods in a storeroom, moving the goods to shelves in the public area of the shop when they are nearly empty, operating the till, and keeping the shop clean. Bob pays Charlotte £30,000/year to do this, of which the government takes £6,000/year in income tax.

Suppose Charlotte starts working on 1 January 2024. What’s her income that year?

Because of income tax, there are actually two answers to this.

Her gross income for 2024 is £30,000: this is how much Bob has to pay to employ her.

Her net income for 2024 is £24,000: this is how much Charlotte actually receives because £6,000 of what Bob pays goes to the government instead of her.

To understand which of these is more important, think about what income means to the employee. Charlotte actually receives £24,000 in cash to add to the stock under her mattress (or, more likely, has £24,000 added to the balance in her bank account). Nowadays, she never even sees the £6,000, because Bob transfers the money straight to the government. Charlotte only knows about it because Bob reports it to her on a pay slip. So really, net income is the relevant one, and that’s what I’m referring to when I write just “income”.

What about other situations?

Income for an employee is pretty straightforward. An employee’s income is the amount of money they’re paid for their work. It’s added to their stock of money, which can then be spent on the things they need or want. But there are lots of unanswered questions still:

What about the income of someone who is self-employed?

Does a firm have an income? Does a government?

If someone borrows money, that lets them buy things now which they otherwise couldn’t have, so is that part of their income?

If Alice and Bob give each other £1,000, does this increase their incomes? If so, doesn’t that make income a meaningless value, because they could both increase their incomes without limit by doing this over and over again?

In the first example above, if Dom spends £100 of what he was paid on wheat from Alice, is this part of Alice’s income, and if so, is there some double-counting going on because the £100 was already part of Dom’s income?

We’ll look at these questions over the coming weeks. Spoiler alert: there is a good, coherent way to define income, but I think that most economists haven’t thought about this carefully enough and rely too much on their intuition, which leads them to some dangerously wrong conclusions.

I believe this is actually happening, which is why I want people to understand this and tell decision-makers that they need to cut it out.