Is Money a Veil Over Barter? (1)

One of the biggest controversies in economics

When people use money for buying and selling, is the economy fundamentally different from a simple barter economy1? Or if we looked at the movement of the goods and services, would we find that behind the “veil” of transactions involving money, what’s going on is essentially just barter — maybe done more efficiently?

The One Lesson has an answer, which most economists probably won’t entirely like, but I expect that some of them really won’t like the answer.

Method

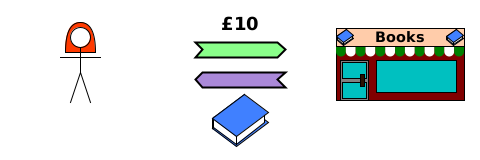

We need to decide what it means for an economy with money to be “essentially” barter. It can’t be that any scenario involving money leaves the real economy (goods and services) exactly as it would be if there were no money. There are obvious counterexamples. For example, Alice buying a book from a bookshop in my very first Substack article:

In the real economy (purple and/or white arrows only), the only change is the transfer of the book from the bookshop to Alice. This wouldn’t normally happen in a barter economy, because it would mean the bookshop had donated the book to Alice.

The reason this isn’t the same as barter is that we’re not comparing like with like. Alice has lost £10 and the shop has gained £10. To see whether a monetary economy is equivalent to barter, we need to see what actions are left over when everyone ends up with the same money they started with.

Examples where money returns to where it started

Two people

Consider this interaction from the article on Bastiat’s broken window fallacy. After a vandal has broken the baker’s window and thrown the glazier’s birthday cake in the bin, the baker buys a replacement window from the glazier for £50 cash, and the glazier buys a replacement cake from the baker for £50 cash.

Unlike in the last scenario, everyone ends up with the same amount of money which they started with. So how have everyone’s assets and liabilities changed? Hopefully it’s clear that the transfers of money cancel each other out, which means that the only changes are the transfer of the window and the transfer of the cake.

Effectively, the glazier and the baker have swapped a window for a birthday cake. It’s the same result as a barter transaction.

What about if there are more than 2 people involved?

Multiple people

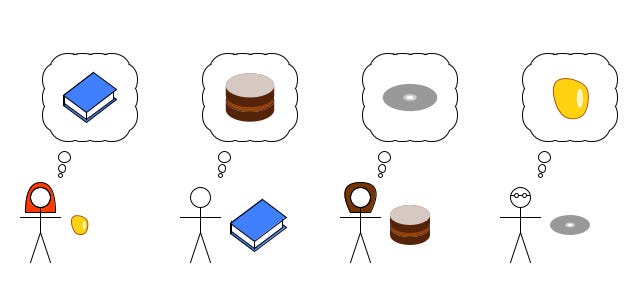

Let’s look at a scenario based on the first article in the money and banking series.

Each person has something, but wants what the next person along has. Suppose Alice also has £10. She can buy the book from Bob for £10. He can then buy the cake from Charlotte for £10. She can buy the DVD from Dom for £10. And he can buy the amber from Alice for £10.

First, just look at the financial economy (green/pink arrows).

In transaction 1, Alice loses £10, and in transaction 4, she regains £10.

Each of the others first gains £10, and then loses £10.

So everyone ends up with exactly the same money as they started with.

Now look at the real economy (purple/white arrows).

Alice has lost some amber, but gained a book.

Bob has lost a book, but gained a cake.

Charlotte has lost a cake, but gained a DVD.

Dom has lost a DVD, but gained some amber.

Once again, the result is simply like barter, as though the 4 people had met, stood in a circle, and passed on what they have to the person on their right, while receiving what they want from the person on their left.

It seems pretty clear that if money (or any other debt asset) is simply being transferred around, and ends up back where it started, the only changes that are left are actions from the real economy. That is, the result is the same as if the people involved had met and bartered their goods and services.

What about when money is actually created in the scenario?

Money creation

As we’ve seen, most money today is created simply by banks creating a new debt. It exists for some time and then is eventually destroyed when the holder writes it off (usually in exchange for the bank either (i) writing off the holder’s loan debt to it, or (ii) giving the holder cash).

So how can we compare like with like, when the scenario involves money creation? The answer is that we need to look at what has changed once the money has been destroyed again.

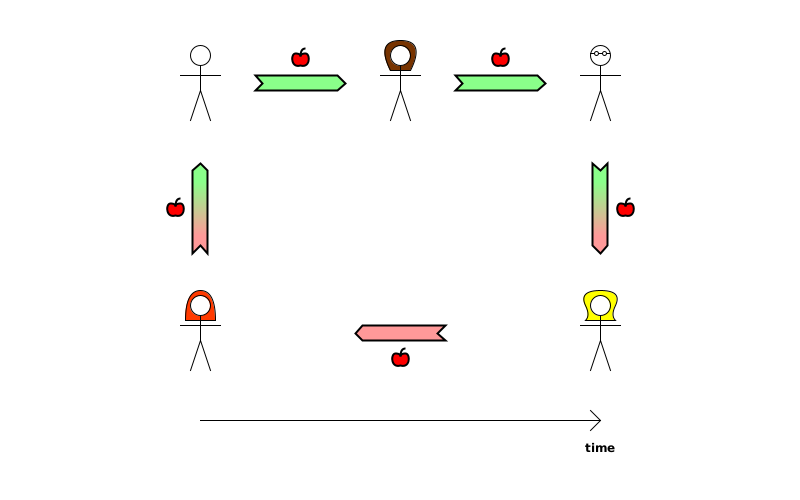

Here’s a simple example, where Alice borrows £10,000 from a bank, and uses it to buy a car.

She then works for an employer for 6 months, earning £10,000 which she uses to repay the loan2.

First follow the actions for the loan:

Created in transaction 1.

Written off in transaction 4.

The asset and liability created in transaction 1 are both destroyed in transaction 4, leaving no trace on anyone’s balance sheet.

Now follow the actions for the new money (the “deposit”):

Created in transaction 1.

Transferred from Alice to etc. in transaction 2.

Transferred from etc. to Alice in transaction 3.

Written off in transaction 4.

This is only slightly more complicated. The asset and liability are created in transaction 1, then the asset is transferred twice before the debt is written off in transaction 4, again leaving no trace on anyone’s balance sheet.

So all that remains is the following:

Alice has exchanged her work for the car. The money simply allowed her to obtain the car before she did the work which paid for it. While it wasn’t a single transaction, the result is still that Alice has swapped her work for the car.

The effect of a debt on balance sheets

Remember that any debt is first created, then both the asset and liability sides of the debt can be passed along a chain of creditors and debtors respectively, and eventually the final creditor agrees that the final debtor no longer owes the debt.

It’s important to understand that every one of these actions can be, and most often is, part of a transaction involving other actions, as we saw in the example of Alice buying a car or working for money.

The effect of a loop of actions like this on anyone’s assets and liabilities is nothing:

Each creditor first gains an asset and then loses it.

Each debtor first gains a liability and then loses it.

So the only changes to anyone’s balance sheet following a scenario in which a debt is created and subsequently written off are the actions which don’t relate to this debt.

This is true for all debts. And this includes all modern money.

What this means is that, once a debt has finally been written off, the only effects which remain are from the actions relating to the real economy — and to other debts. But since this observation applies to all of those debts too, ultimately the entire economy reduces to actions in the real economy:

Production

Transfers of goods

Consumption

Provision of services (which can be thought of as the simultaneous production, transfer and consumption of an immaterial product).

There’s a constant process of unimaginable numbers of debts being created and later written off, so there is never realistically going to be a time when there are no debts outstanding, with all previous economic activity amounting to barter. But each debt outstanding at any point in time is just in the process of moving towards its effects being cancelled out. Each creation of a debt moves the economy further from a pure barter outcome, but it’s on the way to being written off, which will move the economy just as far back towards a pure barter outcome.

In the next article, we’ll see what happens if a debt remains outstanding forever.

Summary

Ultimately, the effects of any debt (which doesn’t remain outstanding forever) are undone, leaving no effect on the economy. The only lasting effects are from the real economy of goods and services.

Money is a veil over barter.

A barter economy is where people trade goods and services for other goods and services, instead of money being involved.

For an example involving paying interest on a loan, see this article.

![[1] (TD) Baker→Glazier {£50 (cash)}. (TT) Glazier→Baker {window}. [2] (TD) Glazier→Baker {£50 (cash)}. (TT) Baker→Glazier {cake}. [1] (TD) Baker→Glazier {£50 (cash)}. (TT) Glazier→Baker {window}. [2] (TD) Glazier→Baker {£50 (cash)}. (TT) Baker→Glazier {cake}.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!FRry!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5208c375-f0de-4e7d-88cb-3334f71abd07_420x300.png)

![[1] (TT) Glazier→Baker {window}. [2] (TT) Baker→Glazier {cake}. [1] (TT) Glazier→Baker {window}. [2] (TT) Baker→Glazier {cake}.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!1mEh!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0a05b724-8aa3-4d21-b109-89e474725144_420x200.png)

![[1] (TT) Bob→Alice {book}. (TD) Alice→Bob {£10 (cash)}. [2] (TT) Charlotte→Bob {cake}. (TD) Bob→Charlotte {£10 (cash)}. [3] (TT) Dom→Charlotte {DVD}. (TD) Charlotte→Dom {£10 (cash)}. [4] (TT) Alice→Dom {amber}. (TD) Dom→Alice {£10 (cash)}. [1] (TT) Bob→Alice {book}. (TD) Alice→Bob {£10 (cash)}. [2] (TT) Charlotte→Bob {cake}. (TD) Bob→Charlotte {£10 (cash)}. [3] (TT) Dom→Charlotte {DVD}. (TD) Charlotte→Dom {£10 (cash)}. [4] (TT) Alice→Dom {amber}. (TD) Dom→Alice {£10 (cash)}.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ex8C!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe6d5d61b-9c55-4073-b2fa-f4658056fb03_560x560.png)

![[1] (TT) Bob→Alice {book}. [2] (TT) Charlotte→Bob {cake}. [3] (TT) Dom→Charlotte {DVD}. [4] (TT) Alice→Dom {amber}. [1] (TT) Bob→Alice {book}. [2] (TT) Charlotte→Bob {cake}. [3] (TT) Dom→Charlotte {DVD}. [4] (TT) Alice→Dom {amber}.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!zj_6!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F42967617-a05d-4bb9-8f27-5ec2a0b9ab6a_560x560.png)

![[1] (CD) Bank→Alice {£10K (deposit)}. (CD) Alice→Bank {£10K (loan)}. [2] (TD) Alice→etc {£10K (deposit)}. (TT) etc→Alice {car}. [1] (CD) Bank→Alice {£10K (deposit)}. (CD) Alice→Bank {£10K (loan)}. [2] (TD) Alice→etc {£10K (deposit)}. (TT) etc→Alice {car}.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!p29Z!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc1117847-e322-454d-a0a0-f4ebc9bd77c0_800x200.png)

![[3] (S) Alice→etc {Work}. (TD) etc→Alice {£10K (deposit)}. [4] (WO) Bank→Alice {£10K (loan)}. (WO) Alice→Bank {£10K (deposit)}. [3] (S) Alice→etc {Work}. (TD) etc→Alice {£10K (deposit)}. [4] (WO) Bank→Alice {£10K (loan)}. (WO) Alice→Bank {£10K (deposit)}.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!eC6o!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd9e4b742-ef10-4979-8cc5-510dbc170584_800x200.png)

![[2] (TT) etc→Alice {car}. [3] (S) Alice→etc {Work}. [2] (TT) etc→Alice {car}. [3] (S) Alice→etc {Work}.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6oT0!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Faa7d921f-183f-4e31-a1bb-581c08f0c6f2_800x200.png)

I disagree with the proposition that money is a veil over barter. I have an objection to the "proof" based on the fact that a balance sheet balances. It does indeed balance but only if you value the components of each transaction as money. If you value ine side of a transaction as a "cake", you lose the permanence of the value. Next week the cake may be stale and of no value. Money has value over time. Cake does not. The fact that a cake does not hold value over time effects its price! The fact that a birthday cake with the wrong date has no value, effects price even more. The advantage of money is that it separates itself automatically from the nature of the purchased service or item. The seconda advantage of money is precision. The idea that four individual could find any set of transaction exactly equal in money equivelence, id practically nil. There would be winners and losers. The losers would often decline the transaction, which would leave the other paties isolated. the only aguement that this proposition solves is that it makes possible the idea of economic equillibribium. I do not belive that this concept is realistic because every buyer and or seller has a different view of the value of the transaction.

Money does look like a veil over barter, but the majority of money created by banks denotes a bank promise and is not created as a debt, as you and Karim (@realonomics) suggest. It is created as a credit, offset by an equal debit. A voluntary promise carries only a moral obligation. It is not a debt obligation, which stems from a prior transaction in which you received someone else’s asset.

Your previous article on “Debt” [2 Jun 2023] rightly says that a debt implies a promise, but the reverse is not necessarily true. Naked promises, in particular, cause this asymmetry and explain why the debit - recorded against your name in a bank’s asset account when it creates money as a credit - carries no debt.

Consider this: deposit a £100 Note at a bank and the bank creates a £100 debit against your name in an asset account, accompanied by a matching bank promise (a £100 credit in your account) that you accept as a substitute for your £100 Note. The same accounting steps apply whether you deposit a £100 BoE Promissory Note or a personal £200,000 Promissory Note. For auditing purposes, the bank must enter the debit against your name, simply to identify you as the depositor in each case. You become a creditor of the bank in both cases, and for the same reason: you own the credit because you made the valuable deposit.

It is an accounting mistake to think that your £200,000 promise puts you “in DEBIT”, meaning you “owe” the bank £200,000, as a DEBT. Like the £100 note, your £200,000 promise is naked because it actually increases the bank’s total assets by £200,000, and no existing bank asset is affected by it. Banks know the “note business”. They willingly accept promissory notes as valuable assets.

With the £100 BoE note, the resulting £100 credit and £100 debit offset each other completely, just as they do with your £200,000 promise. But you don’t ‘owe’ the bank £200,000 any more than you ‘owe’ it £100 after you deposit your £100 BoE promissory note. The £100 debit and £100 credit destroy any notion of a £100 loan or implication of a £100 “debt” owed to the bank. In each case, the credit is your asset, the debit is the bank’s asset, and both your promise and the bank’s promise must be kept.

That is why the bank can’t “lend” you either of those credit items, and if you don’t believe the Bank of England on that point, ask any competent accountant whether you can lend the credit balance in any of your liability accounts. Once you see the accounting logic that says the bank can’t lend you the £100 Credit in the case of the £100 Note deposit, because it is already your asset (and the bank’s liability), you should accept the same logic for the £200,000 deposit as well, since both are naked promises.

To create the illusion of a “£200,000 loan” in the second case, a bank MUST therefore disguise these accounting facts, and does so by inserting a deceptive narrative into its accounting record. Since May 2023, my Substack (Forensic Focus) has been exposing clear evidence of this ongoing deception by banks in Australia (see articles #2, #3, #5 & #6) and in Bavaria, against Richard Werner (see article #10).

For all the good accounting analysis they do, Steve Keen and Richard Werner have yet to make this “giant leap”.