Macroeconomics (2)

The whole "real" economy

In the last article, we saw what’s meant by the “real” economy: the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services (the actions with purple and/or white arrows). Here we’ll see how it’s possible to get an intuitive understanding of the whole real economy: every single action involving goods and services.

The trick to understanding a complex system is to break it into smaller pieces which are easier to understand by themselves. Unfortunately, most economists think of a transaction (e.g. Alice buys 5 apples from Bob for £1) as the smallest unit of economic activity, and they end up limiting themselves to dividing the economy into groups of transactions1.

But treating the simpler economic action as the smallest unit of economic activity lets us split up the economy in a completely different way: we can follow a single good (or service2) from production to consumption, whether that’s almost instantaneous (e.g. a doughnut cooked to order) or takes many years (e.g. a car). And once we’ve understood the effects on the economy of this life cycle of one good, the effects on the economy of all activity in the real economy is just the sum of these individual effects.

Life cycle of a tangible asset

Every tangible asset, past, present or future, goes through essentially the same life cycle: it’s produced, then passed along a chain of ownership from the first owner (the producer) to the final owner (the consumer), and finally it’s consumed. Let’s look at an example—a single apple:

Alice grows the apple (and 999 others) in her orchard.

She sells it (and the other 999) to Bob, a wholesaler.

Charlotte, a shopkeeper, buys the apple (and 99 of the others) from Bob.

Dom buys the apple (and 4 others) from Charlotte’s shop.

Next day, Dom eats the apple.

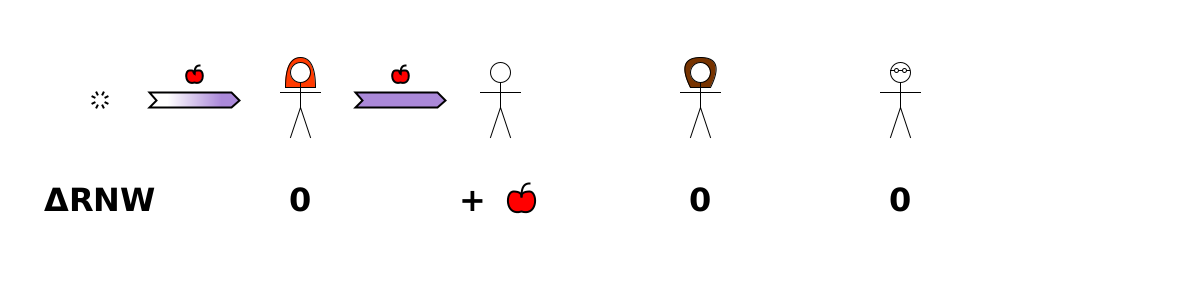

Here, we’re only going to look at the actions which affect the apple, and not the actions in which something is given in return. What effect do just these actions have on each person’s raw net worth3 at each stage from production to consumption, compared to what would have happened if the apple had never been produced?

First, before the apple was produced:

Obviously nobody’s RNW has been changed by these zero actions.

Now consider what happens after Alice harvests the apple:

At this point, Alice’s RNW has increased by the apple. Nobody else’s RNW is affected.

What about after Alice sells the apple to Bob?

Now the effect of this apple’s existence on Alice’s RNW is back to zero, as it was before she harvested it: her RNW both increased and decreased by the apple. But Bob’s RNW has increased by the apple.

The pattern continues:

Both Alice and Bob have both gained and lost the apple, so they are back to where they started. But Charlotte has only gained it, so her RNW has increased by the apple.

Let’s skip the obvious next step, and go straight to the end, after Dom has eaten the apple:

At this point, each person’s RNW has both increased and decreased by the apple, so everyone is back to where they started.

To summarise, at any point in time between the production and the consumption of a tangible asset:

The RNW of the current owner has increased by the asset.

Nobody else’s RNW is affected.

This is a more sophisticated understanding of the economy than we saw in the first article on macroeconomics, because instead of imagining a single pile of tangible assets for the whole world, each person has their own individual pile of the things they own, and the things move from one pile to another over time.

The whole real economy

The whole real economy is just a vast network of these chains which distribute goods (and services) from producer to consumer. The effect of a chain of actions is to increase the current owner’s RNW by the tangible asset.

Let’s just see one simple example of how these chains can interact. Alice produces an apple, and transfers it to Bob, who eats it. Bob produces a loaf of bread, and transfers it to Alice (at the same time as Alice transfers the apple to him), and she eats it. Here are the two individual chains:

And when we put them together, with the first chain running along the top from left-to-right, and the second chain running along the bottom from right-to-left, we see the barter transaction in the middle where the two chains meet:

Wherever chains meet, there’s a transaction where one tangible asset on its way from production to consumption is exchanged for another, following its own path from production to consumption.

Every production, transfer tangible asset, consumption or service action which has ever occurred, or ever will occur, appears in exactly one of these chains.

Summary

To understand the real economy, we can break it into smaller pieces: one group of actions for each tangible asset (or service) ever produced. Each of these follows a chain from producer to consumer, and along the way the actions add the asset to the current owner’s RNW (giving them to ability to consume it or pass it on), and have no effect on anyone else’s RNW.

Where two chains meet, this represents a barter transaction: one person swapping one tangible asset for someone else’s other tangible asset.

The normal ways they do this are to group transactions by (i) the sectors involved (firms, households, financial, government, foreign), and (ii) the time period (usually year) when they occurred.

As we saw in the article on services, you can think of a service as the simultaneous production, transfer and consumption of an immaterial good, so references to goods in this article apply to services too.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.

![[Top chain] (Produce) void → Alice {apple}. (Transfer) Alice → Bob {apple}. (Consume) Bob → void {apple}. [Bottom chain] (Produce) void → Bob {bread}. (Transfer) Bob → Alice {bread}. (Consume) Alice → void {bread}. [Top chain] (Produce) void → Alice {apple}. (Transfer) Alice → Bob {apple}. (Consume) Bob → void {apple}. [Bottom chain] (Produce) void → Bob {bread}. (Transfer) Bob → Alice {bread}. (Consume) Alice → void {bread}.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!5D9F!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F901098b5-dbc7-4123-b594-cb801c354b6e_640x300.png)