The Financial Economy (1)

Why do we need debts?

What’s the point of the financial economy? After all, as we’ve already seen, the real economy by itself includes all the production, distribution and consumption of all goods and services ever produced.

Read on for the answer.

(TL;DR: the financial economy is needed to split complex transactions involving many people into simpler transactions each of which leaves all the participants satisfied).

The real economy is not enough

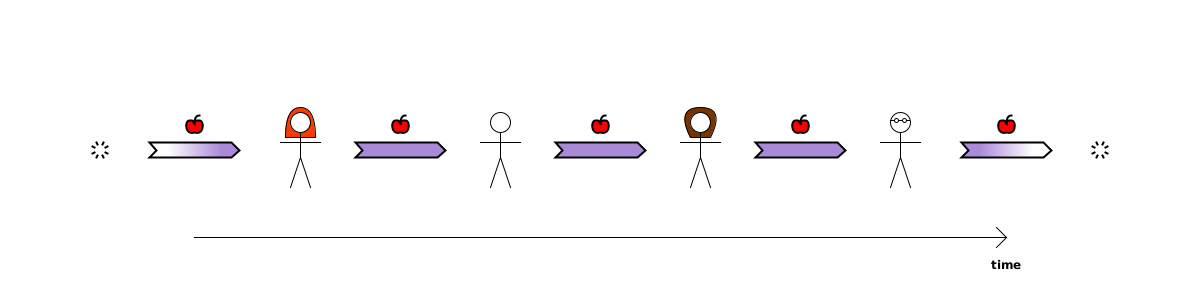

We’ve seen how to understand the real economy as a (huge) number of chains of ownership—one for each good or service—like the one in the diagram below.

These chains include every action involving every single good or service ever produced. They represent the entire real economy for all of time. But if that was all that happened in the whole economy, the only way that someone could be paid for transferring a good or service to the next person in the chain would be a barter transaction, where a good or service from a different chain is transferred in the opposite direction at the same time, such as Alice swapping her apple for Bob’s bread below:

There are also two situations where nothing is given in return:

The current owner of a good gives it to someone else (or a provider performs a service for someone else) as a gift, possibly with an informal expectation (or hope) of receiving something back later.

A good is taken from its current owner (or a service is coerced out of a provider) by theft, force or fraud.

But barter and transfers are only a small part of economic activity in the real world. Normally, someone who transfers a good or service to someone else wants to receive something valuable in exchange, but not usually a good or service to own or consume now. And that’s where the financial economy comes in.

In the real economy, there is only one way for Bob to transfer some of his raw net worth to Alice in exchange for her transferring an apple to him: transferring a good (or service). The financial economy of debts provides an extra four ways for him to exchange something valuable:

Create a new debt owed to Alice;

Transfer an existing debt asset, currently owed to him by someone else, to Alice;

Take over an existing liability, currently owed by Alice to someone else; or

Write off a debt owed to him by Alice.

These actions make up the financial economy. Numbers 1 and 2 in particular are extremely common. 1 includes buying on credit (standard practice for firms buying supplies), and 2 includes paying with cash, cheque, debit card or bank transfer.

As in the article on the real economy, let’s consider the banking example again, where 4 people each have one thing, but want what the next person has. This time, we’ll show the real economy actions on the left and the financial economy actions (loan, purchases and repayment) on the right. As before, we’ll look at the scenario at 2 different stages:

At the end of the complete scenario, and

Half-way through.

Complete scenario

In the scenario, Alice doesn’t have any amber with her in Bob’s bookshop, and Bob won’t accept her personal IOU. Fortunately, Eve happens to be in the shop, and everyone trusts her IOUs, so Alice swaps IOUs with Eve.

![[LEFT: real] (2) Bob transfers book to Alice. (3) Charlotte transfers cake to Bob. (4) Dom transfers DVD to Charlotte. (5) Alice transfers amber to Dom. [RIGHT: financial] (1) Eve and Alice swap new IOUs. (2) Alice transfers Eve's IOU to Bob. (3) Bob transfers Eve's IOU to Charlotte. (4) Charlotte transfers Eve's IOU to Dom. (5) Dom transfers Eve's IOU to Alice. (6) Eve and Alice write off their IOUs to each other. [LEFT: real] (2) Bob transfers book to Alice. (3) Charlotte transfers cake to Bob. (4) Dom transfers DVD to Charlotte. (5) Alice transfers amber to Dom. [RIGHT: financial] (1) Eve and Alice swap new IOUs. (2) Alice transfers Eve's IOU to Bob. (3) Bob transfers Eve's IOU to Charlotte. (4) Charlotte transfers Eve's IOU to Dom. (5) Dom transfers Eve's IOU to Alice. (6) Eve and Alice write off their IOUs to each other.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!UCPl!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F03b4bdc4-9ad5-4916-9cd1-2fa29e8c17c2_1280x640.png)

As always, let’s check how the actions affect each person’s raw net worth1. The table below shows how each person’s RNW is changed by the actions in the real economy, the actions in the financial economy, and all actions combined.

Notice from the middle column that over the whole scenario, the financial economy has made absolutely no difference to anyone’s RNW: the increases and decreases cancel each other out. (Check this in the arrow diagram by comparing the arrows pointing to and away from each person).

The changes in the real economy are the outcome which everyone desires. And so the total (real+financial) result is simply the desired outcome.

So the financial economy has no lingering effect after the desired result in the real economy is obtained. So what was the point? To understand that, we need to look at a point in time before the scenario is complete.

Half-finished scenario

Let’s look at the scenario just after Bob has swapped Eve’s IOU for Charlotte’s cake.

Here’s a table showing how the actions affect each person’s RNW.

Real economy. Here, Bob has lost a book and gained a cake, which is exactly what he was aiming for. But Alice has gained a book with no loss, while Charlotte has simply lost a cake with no gain.

If we just look at the real economy, Alice seems to have got something for nothing, and Charlotte seems to have given up something without getting something in return. But this is where the point of the financial economy becomes clearer.

Financial economy. In the financial economy actions, Alice’s RNW has decreased by a piece of amber, and Charlotte’s RNW has increased by a piece of amber. These actions compensate for the changes in the real economy, leaving both Alice and Charlotte satisfied.

In terms of RNW, in total Alice has swapped amber for a book, and Charlotte has swapped a cake for amber. Charlotte doesn’t want to end up with amber, but she’s satisfied for the moment because she’s confident that she can swap it for the DVD which she actually wants.

Explanation

The real economy includes all of the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services. But it’s rare for two people each to want what the other person has and have what they want at the same time. It’s far more likely that several people (4 in the example above, perhaps hundreds in reality) will need to be involved in one big trade for everyone to be satisfied with the final outcome. Coordinating a big trade involving many people would be difficult enough, but even discovering which people to bring together is an extremely difficult problem by itself.

What’s needed is to break each enormous, complex trade into smaller parts, each involving at most a few people—preferably just 2. However, as we saw in the half-finished scenario above, if the only economic actions are from the real economy, it could leave someone vulnerable to giving up something valuable but not receiving anything valuable in return—like Charlotte who has given up a cake but hasn’t received any goods or services yet.

The financial economy solves this problem by making each smaller part into a transaction in its own right. Even though Charlotte has given up a real cake, she has received an IOU (owed by Eve) in return, and as Eve is both willing and able to keep her promise, Charlotte can be sure of getting something valuable in the real economy in exchange for her cake. Of course, when someone exchanges real goods or services for a promise, they are in a more vulnerable position than if they had received something real. The debtor might try to evade responsibility for their debt, or might simply become insolvent through misfortune. People have to take into account the risk of a promise not being kept when they agree a price in a transaction. But as long as these are rare exceptions, the benefits to society of such a flexible system appear from experience to be enormous.

Summary

While the real economy consists of all production, distribution and consumption of goods and services, which is what economics is all about, it only allows for a barter economy (including commodity money), which is quite inefficient, or an economy in which give and take is managed informally.

The financial economy makes the economy work vastly more efficiently by allowing people to trade some of their RNW without having to transfer goods or services at that point in time. This means that the vast majority of complex trades can be broken into a number of tiny transactions, usually involving just 2 people, and each of which leaves everyone satisfied. As long as debtors are generally willing and able to keep their promises, the system works extremely well.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, meaning that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.

![Two chains with barter transaction in middle. [Apple] void→Alice→Bob→void. [Bread] void→Bob→Alice→void. Two chains with barter transaction in middle. [Apple] void→Alice→Bob→void. [Bread] void→Bob→Alice→void.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!XzRa!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb6b42ce8-d552-4b60-98db-f3e7a66e0a22_420x300.png)

![Changes to RNW. [Real] (Alice) - amber + book; (Bob) - book + cake; (Charlotte) - cake + DVD; (Dom) - DVD + amber. [Financial] All 0. [Total] Same as Real. Changes to RNW. [Real] (Alice) - amber + book; (Bob) - book + cake; (Charlotte) - cake + DVD; (Dom) - DVD + amber. [Financial] All 0. [Total] Same as Real.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!5FcE!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6a8428ce-aadd-433a-b97a-197078892cf8_800x448.png)

![[LEFT: real] (2) Bob transfers book to Alice. (3) Charlotte transfers cake to Bob. [RIGHT: financial] (1) Eve and Alice swap new IOUs. (2) Alice transfers Eve's IOU to Bob. (3) Bob transfers Eve's IOU to Charlotte. [LEFT: real] (2) Bob transfers book to Alice. (3) Charlotte transfers cake to Bob. [RIGHT: financial] (1) Eve and Alice swap new IOUs. (2) Alice transfers Eve's IOU to Bob. (3) Bob transfers Eve's IOU to Charlotte.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Y71n!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7a4c2628-27d4-4918-984a-e2f2d5099e90_1280x640.png)

![Changes to RNW. [Real] (Alice) + book; (Bob) - book + cake; (Charlotte) - cake; (Dom) 0. [Financial] All 0. [Total] (Alice) - amber; (Bob) 0; (Charlotte) + amber; (Dom) 0. [Total] (Alice) - amber + book; (Bob) - book + cake; (Charlotte) - cake + amber; (Dom) 0. Changes to RNW. [Real] (Alice) + book; (Bob) - book + cake; (Charlotte) - cake; (Dom) 0. [Financial] All 0. [Total] (Alice) - amber; (Bob) 0; (Charlotte) + amber; (Dom) 0. [Total] (Alice) - amber + book; (Bob) - book + cake; (Charlotte) - cake + amber; (Dom) 0.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!3tSx!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F40b38999-0e48-4121-be8f-a138c716f669_800x448.png)