The UK Exchequer (11)

Illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson study — Government Spending (7)

This is the eleventh in a series of articles illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson (BTW) study “An Accounting Model of the UK Exchequer”. It completes the section on government spending. After this, I’ll take a break from this very long series, and return to it later to look at cash management (government borrowing), and tax and national insurance (government income).

As in previous articles about the BTW study, I’ll be cross-referencing it by putting section numbers in square brackets.

This last article on government spending is based on section [5.6], which discusses the “Contingencies Fund” (CCF)1, which section [3.1.3] tells us is used “for urgent payments in excess of quantities already authorised by Parliament”. It allows the government to spend more than Parliament has authorised2, by drawing on the Consolidated Fund (CF) and repaying “within the same or following financial year out of subsequently authorised expenditure”.

The most important thing is to notice how each party’s raw net worth (RNW) changes at each stage, by looking at the arrows pointing towards them (RNW↑) and away from them (RNW↓). In particular, notice how in most steps, nobody’s RNW is actually changing overall.

Unfortunately, like some of the longer articles earlier in this series, this won’t fit in an email, so please follow the link (click on the article title) to see the whole article.

Basics of Exchequer Spending (ctd) [5]

The Contingencies Fund and Covid-19 [5.6]

This section mentions that the CCF was multiplied by a factor of 25 (from 2% of the previous year’s approved expenditure to 50%) in 2020 when the government decided to declare Covid-19 as a pandemic and introduce major restrictions on economic and social activity. This was an increase from ~£10 billion to ~£266 billion. “As of September 2020, […] £121 billion had been advanced to government departments […] of which £90 billion was ‘repaid’ following formal Parliamentary authorisation”.

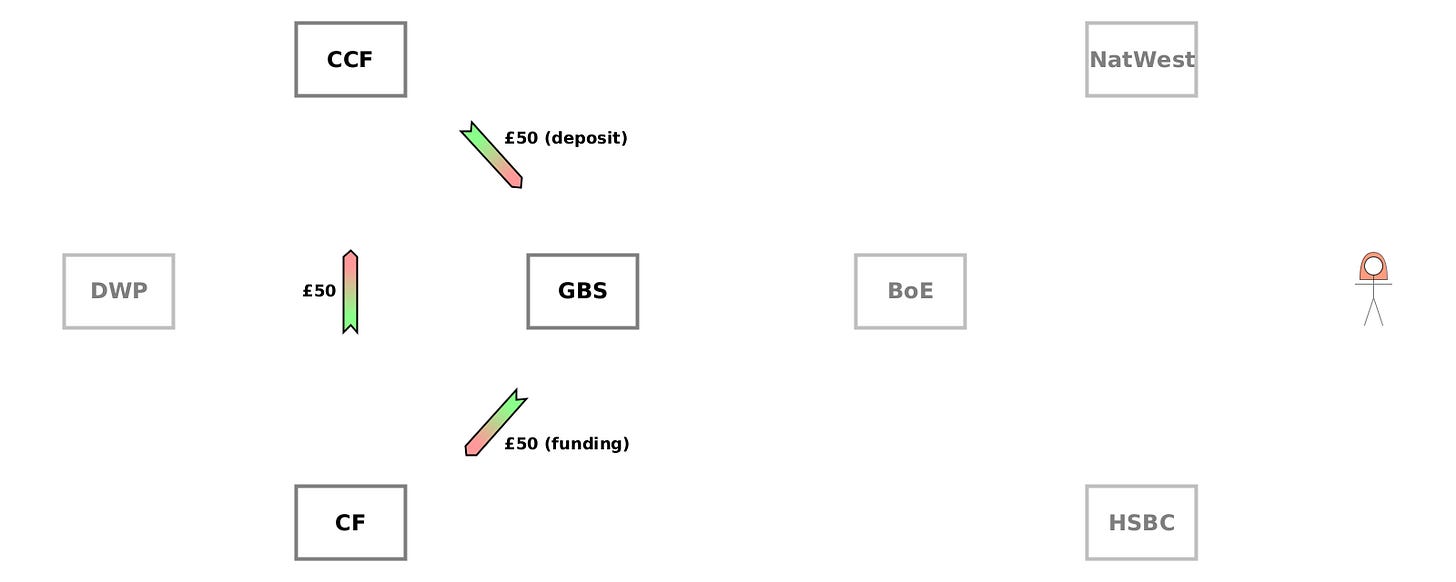

In this scenario, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) essentially borrows £50 from the CCF, which in turn obtains it from the CF.

It continues with DWP spending the £50, and then the government receiving £50 from some other source3 . Finally, Parliament approves the expenditure which has already occurred, and CCF is repaid.

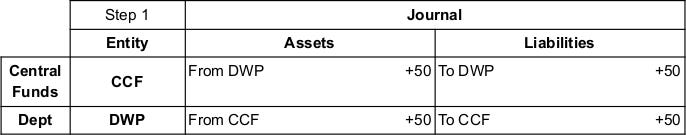

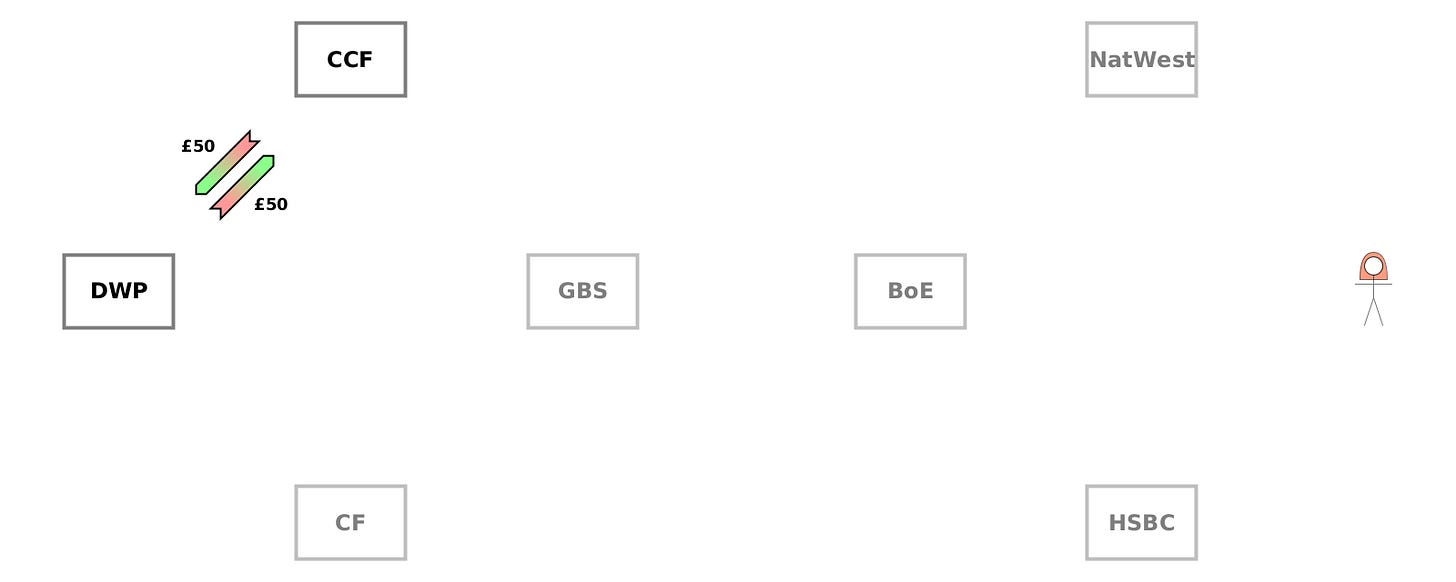

Step 1 — CCF advance to DWP

DWP, realising it needs to make a payment which hasn’t been authorised by Parliament, obtains CCF’s promise to provide money for it to spend, and promises to repay it later.

This is the same pattern as borrowing from a bank: there are two “New Debt” actions, each party promising to pay the other £50 in future.

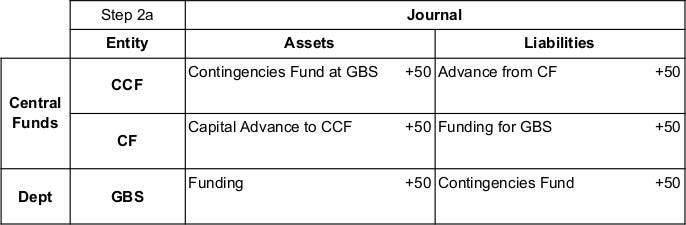

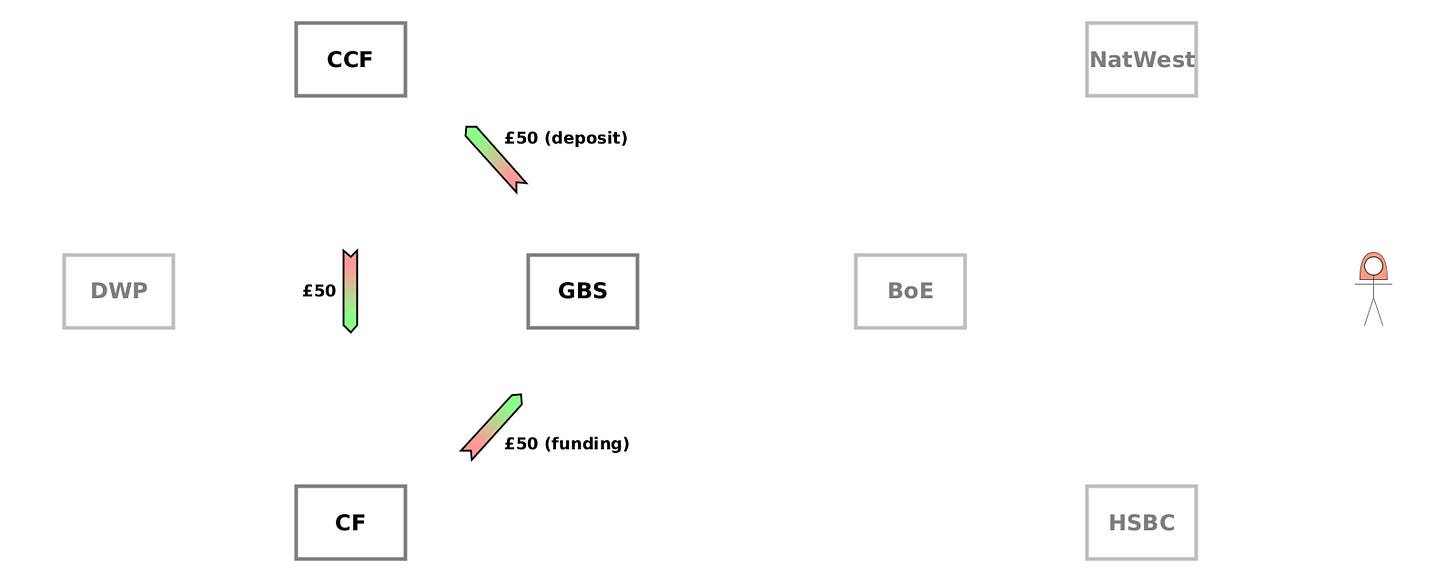

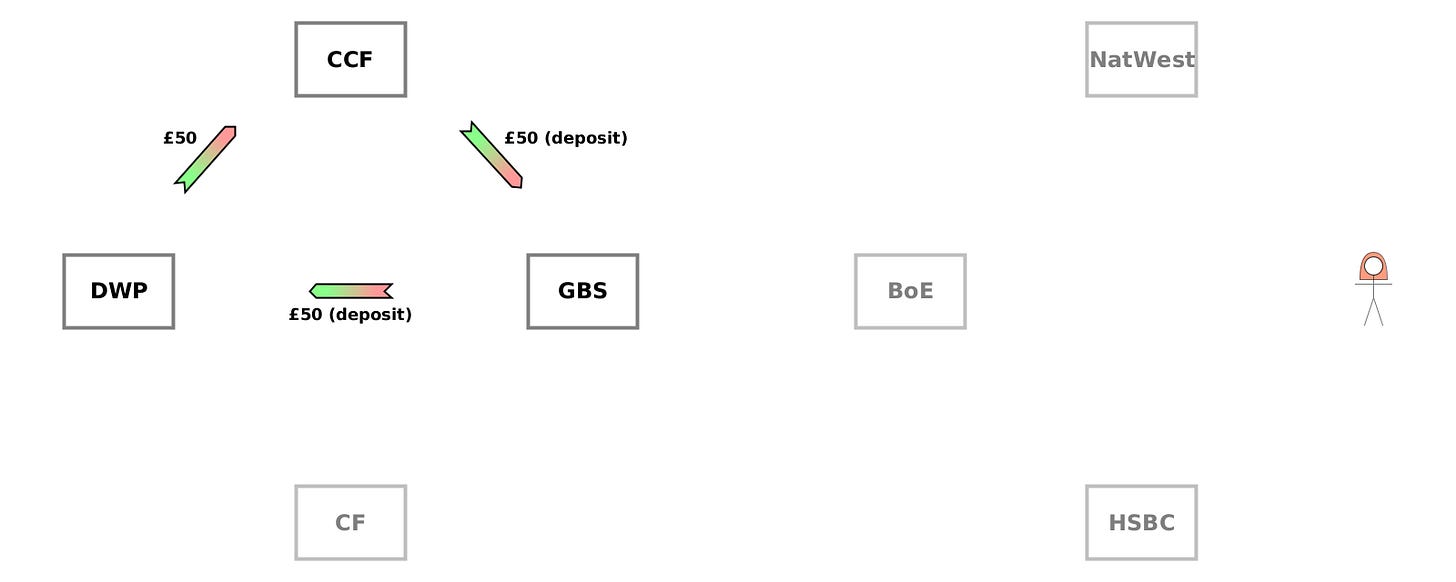

Step 2 — DWP receives GBS deposit

DWP can’t spend a debt owed by the CCF: as we’ve seen before, it needs a deposit at GBS.

In step 2a, CCF obtains a deposit at GBS, which in turn receives CF’s promise to pay. And CCF promises to repay CF. This is very similar to a department receiving a deposit for authorised spending. But unlike allocation of authorised spending for a government department, the expectation here is that CCF actually will repay CF.

This is a transfer of £50 of RNW around a loop: CF→GBS→CCF→CF.

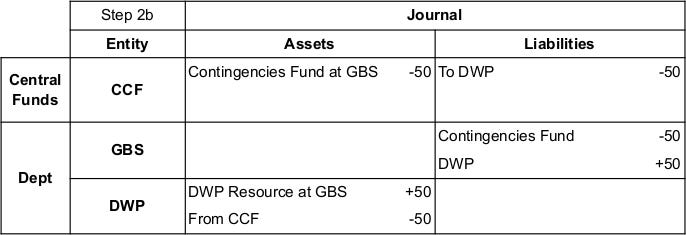

In step 2b, CCF transfers £50 to the DWP account at GBS, fulfilling its earlier promise.

This is just like a transfer between accounts at the same bank, as we saw in section [4.1], but in addition DWP writes off CCF’s debt, since it’s now kept its promise. So this is a transfer of £50 of RNW around a loop: CCF→GBS→DWP→CCF.

Step 3 — balance sheet

Step 3 in the BTW study just shows balance sheets of the different actors at this stage.

Step 4 — DWP spending

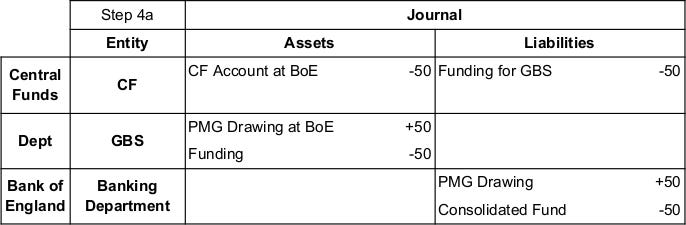

As we’ve seen in earlier articles, for DWP to spend its deposit, GBS needs public deposits at the Bank of England (BoE), which it obtains from the CF. If CF doesn’t have any already in its account at the BoE, it can borrow from the BoE, which creates new public deposits.

Step 4a shows the CF transferring £50 from its account at the BoE to GBS’s account. GBS writes off the debt from CF, now that CF has kept its promise.

As we’ve seen before, there are several inconsistencies in the BTW study between the balance sheets and the journals. The journals generally assume there is already money in the CF’s account at the BoE, but the balance sheets start with the account being empty. Here, I’ll follow the journals, as it’s simpler. (We’ve already seen several examples where the CF draws on its overdraft facility with the BoE because it doesn’t have enough in its account, so there’s no need to add that complication here).

This is a common settlement pattern: CF transfers £50 to GBS indirectly (via the BoE), and in exchange, GBS writes off the £50 debt from CF. It’s a transfer of £50 of RNW around a loop: CF→BoE→GBS→CF.

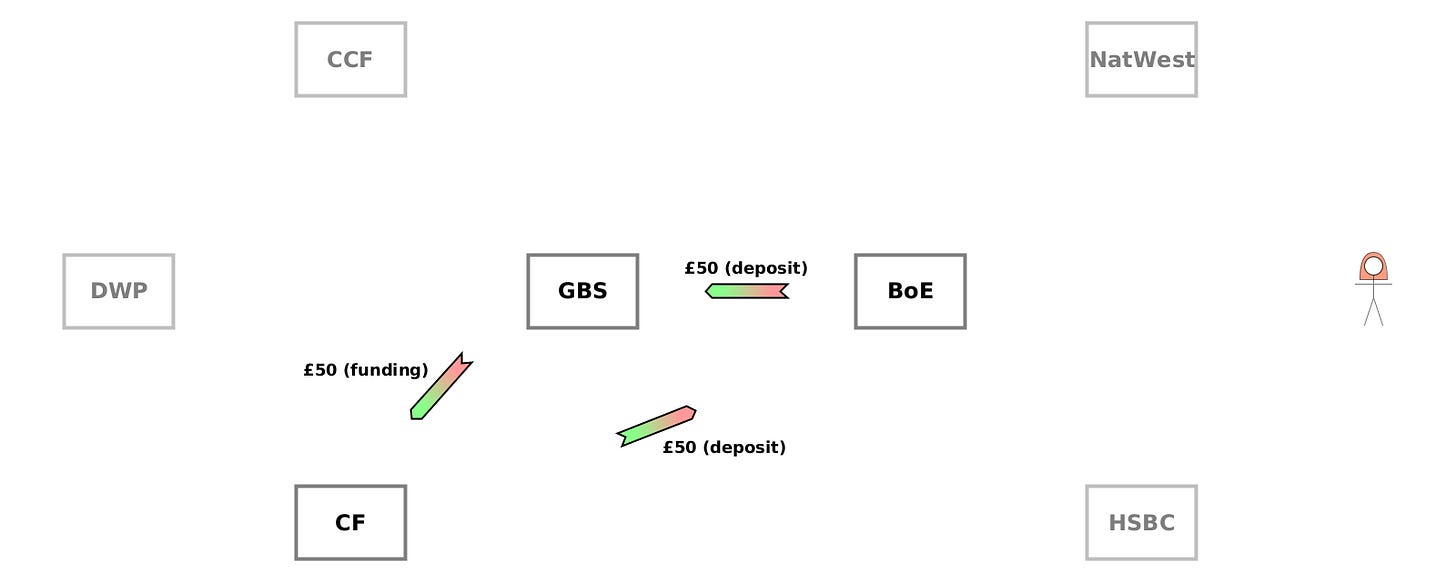

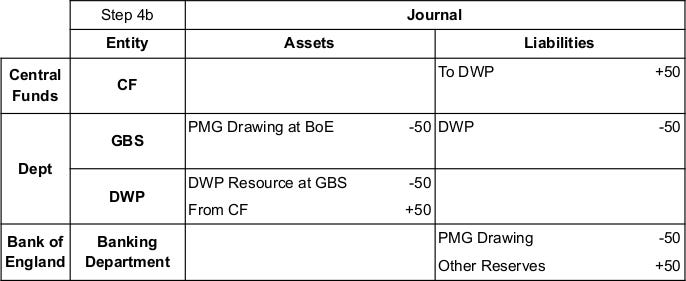

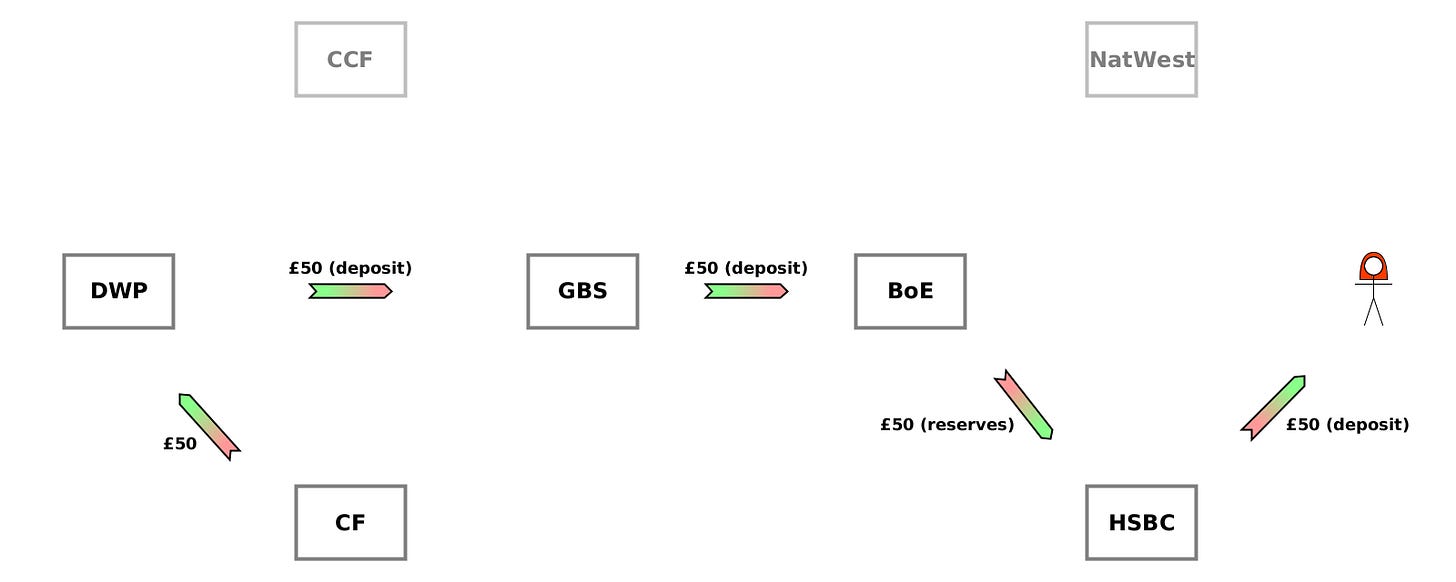

Step 4b shows DWP making a £50 payment.

In fact this journal in the BTW study doesn’t include rows for the recipient’s bank (HSBC) or the recipient (Alice). This would be the same as step 2 of section [5.4], and the following extra entries would appear:

(HSBC Assets): Reserves +50

(HSBC Liabilities): Deposit for Alice +50

(Alice Assets): Deposit at HSBC +50

The arrow diagram below includes these extra entries (the green tip of the arrow from BoE to HSBC, and the pink-to-green arrow from HSBC to Alice).

This is a chain of transfers of £50 of RNW: CF→DWP→GBS→BoE→HSBC→Alice. CF’s RNW↓ by £50, while Alice’s RNW↑ by £50.

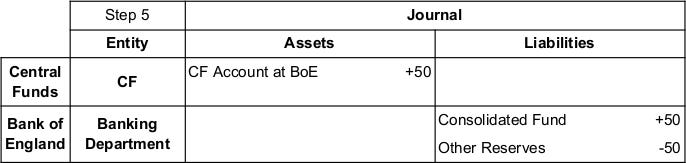

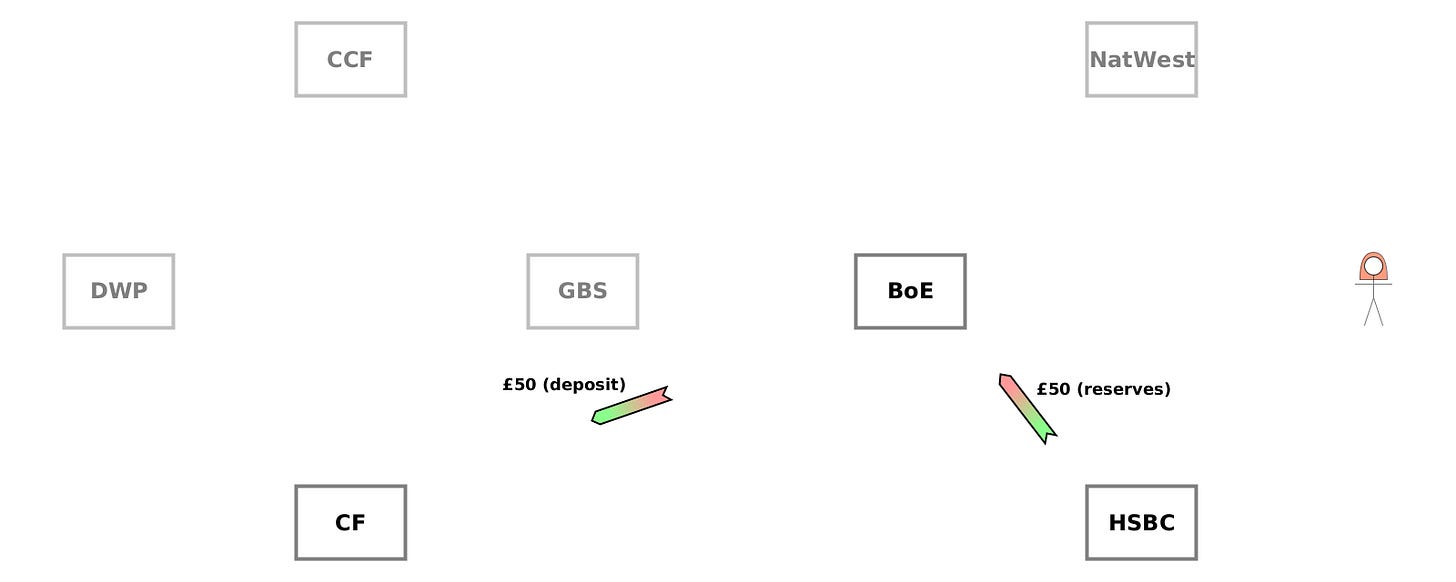

Step 5 — government cash inflow

Here, the BTW study refers to an inflow of £50 cash to the CF, without going into the details. It suggests that this could be from cash management (issuing a new government bill), but since we haven’t seen that yet4, let’s assume for simplicity that it actually comes from HSBC incurring and immediately paying a tax5.

The BTW study’s journal doesn’t actually show rows for the source of the money. In the simplified example here, it is just HSBC, and the following entry would appear in the journal:

(HSBC Assets): Reserves -50

Again the arrow diagram below the journal includes this extra entry (the green base of the arrow from HSBC to BoE).

This is a chain of transfers of £50 of RNW: HSBC→BoE→CF. HSBC’s RNW↓ by £50, while CF’s RNW↑ by £50.

Step 6 — balance sheet

Step 6 in the BTW study just shows balance sheets of the different actors at this stage.

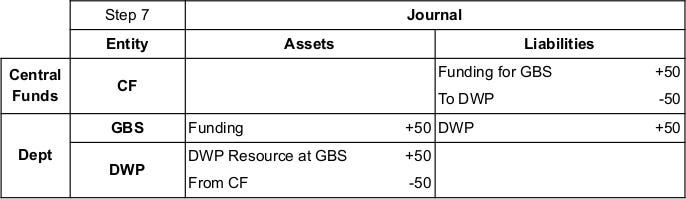

Step 7 — funding (for past spending)

At this stage, Parliament votes to approve the spending which has already occurred.6 The result is similar to the normal supply funding which we’ve seen before.

This is a transfer of £50 of RNW around a loop: CF→GBS→DWP→CF.

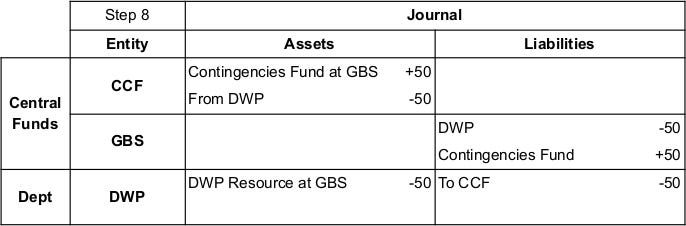

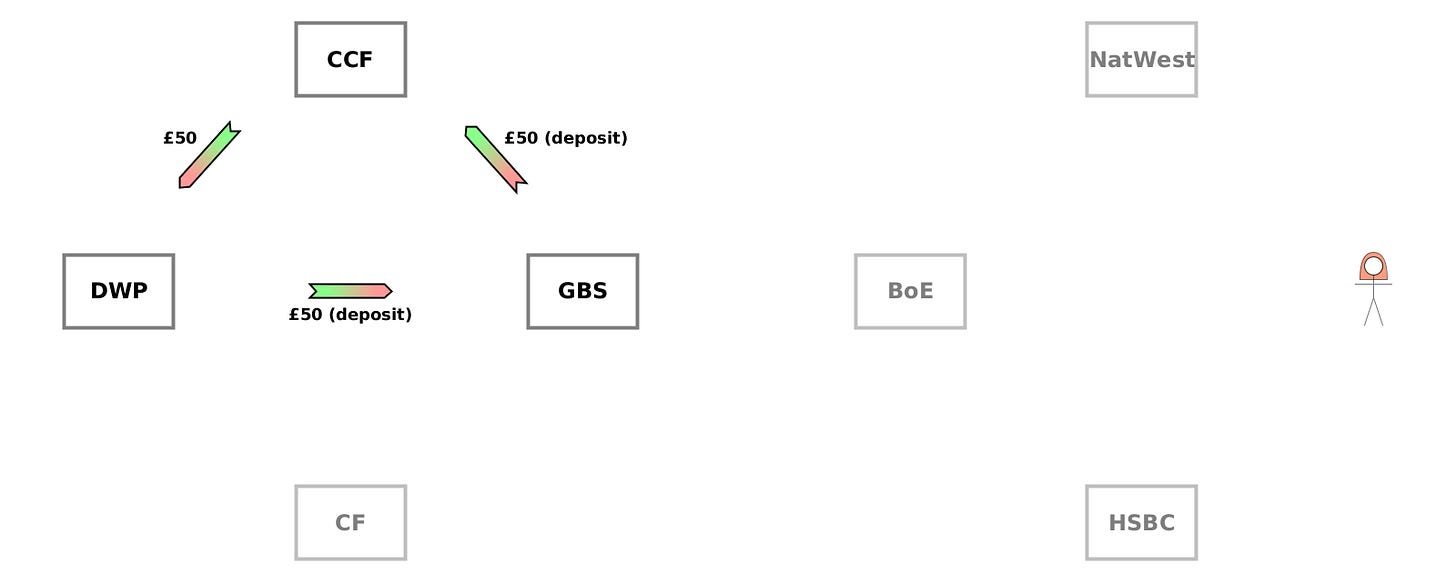

Step 8 — DWP repays CCF

Now that DWP has a £50 deposit at GBS again, it uses it to repay CCF, which writes off DWP’s debt to it in exchange.

This is a transfer of £50 of RNW around a loop: DWP→GBS→CCF→DWP.

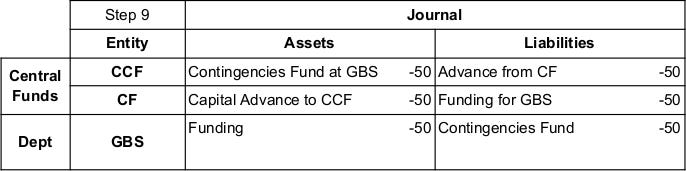

Step 9 — CCF repays CF

Finally, CCF uses its balance at GBS to repay CF.

This is a transfer of £50 of RNW around a loop: CCF→GBS→CF→CCF.

Overview

As we’ve seen throughout this series on government spending, almost all activity in this scenario involves debts which just transfer RNW around a loop. The only steps which actually change anyone’s RNW are:

Step 4b (CF’s RNW↓ £50, Alice’s RNW↑ £50).

Step 5 (HSBC’s RNW↓ £50, CF’s RNW↑ £50).

There were 27 actions in the complete scenario. But some of the “new debt” actions (pink-to-green arrows) are undone by corresponding “write off debt” actions (green-to-pink arrows). What’s left over after these cancellations?

Just this:

Alice has been paid £50 by DWP (which is in turn compensated by CF). HSBC has been taxed £50, which is sent to CF. So the only change remaining is a new £50 deposit debt from HSBC to Alice!

It’s always interesting to look at what changes remain after a new debt has finally been written off.

Summary

The (Civil) Contingencies Fund (CCF) allows the government to make urgent payments which haven’t been authorised in advance by Parliament. Traditionally this is for modest amounts (up to 2% of the budget).

The CCF borrows from the Consolidated Fund (CF), receiving a deposit in the Government Banking Service (GBS). It lends this to a department which can then spend it. Once this spending has been retroactively authorised by Parliament, all the borrowing is repaid, and the situation returns to how it would have been if the spending had been authorised in advance in the normal way.

The Contingencies Fund was formerly known as the Civil Contingencies Fund. The “CCF” abbreviation distinguishes it from “CF” for the Consolidated Fund.

2% of authorised expenditure, according to the BTW study, but temporarily increased to 50% in 2020.

The BTW study doesn’t show full details about where this comes from; it suggests borrowing, but doesn’t show the accounting for it which is explained in section 6.

Cash management and debt management appear in chapter [6].

We haven’t seen tax yet either, but it’s easy to understand that this simple example would just amount to a transfer of reserves from HSBC to the Consolidated Fund’s BoE account. In fact, the transfer would go through the bank (Barclays at the time of the BTW study) which initially collects taxes on behalf of the government and transfers the money to the government in batches.

I don’t know what happens if Parliament doesn’t approve of the spending which was enabled by the CCF.