The UK Exchequer (2)

Illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson study — Banking (1)

This is the second in a series of articles illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson (BTW) study “An Accounting Model of the UK Exchequer”. Here, we’ll start looking at the UK banking system.

As I mentioned in part 1, I’ll be cross-referencing the BTW study by putting section numbers in square brackets.

For each journal1 from the BTW study, I first show exactly the same information in an intuitive action diagram (with one arrow per action), which is the main point of this series. To help to interpret it, this is followed by a detailed description of each action in the diagram — but again this is exactly the same information.

So without further ado, it’s time to start illustrating the journals for the study’s banking scenarios, using the arrow notation for economic actions.

Unfortunately, this won’t fit in an email, so please follow the link (click on the article title) to see the whole article.

A simple model of the UK banking system [4]

The simplest bank payment [4.1]

This scenario is a payment of £5 from one customer of HSBC to another.

There are actually 2 versions of the scenario. In the first, Alice (“Customer 1”) starts with at least £5 in her bank account before she makes the payment to Bob (“Customer 2”). In the second, she starts with a zero balance, and needs to call on an overdraft facility to make the payment.

Version 1: Payment from existing balance

HSBC simply decreases Alice’s account balance by £5, and increases Bob’s account balance by £5. This is a single action:

Alice→Bob {£5 (deposit)}: Transfer debt asset.

[Alice] A↓

[Bob] A↑

Version 2: Payment by using overdraft

By using the overdraft facility, Alice owes a new debt to HSBC. So there are 2 actions here:

Alice→HSBC {£5 (loan)}: New debt.

[Alice] L↑

[HSBC] A↑HSBC→Bob {£5 (deposit)}: New debt.

[HSBC] L↑

[Bob] A↑

You can think of this as Alice paying Bob indirectly:

Alice pays HSBC £5…

to pay Bob £5.

A simple interbank payment [4.2]

Here, Alice is making a £5 payment to Charlotte (“Customer 3”), but this time there’s a complication: Charlotte banks with a different bank (Lloyds). In this scenario, Alice does have enough in her account to make the payment.

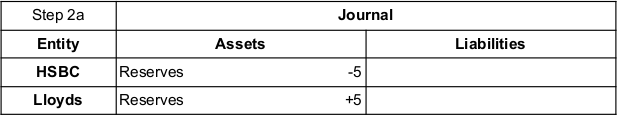

There are multiple steps to this scenario. (See the top-left of the journal tables for the step number).

Step 1 — Payment

Step 1a shows Alice losing £5 of deposits, and Charlotte gaining £5 of deposits.

There are 2 actions (and hence 2 arrows) here. Something is missing, and it’s immediately clear what that is from the action diagram:

Alice→HSBC {£5 (deposit)}: Write off debt.

[Alice] A↓

[HSBC] L↓HSBC→Charlotte {£5 (deposit)}: New debt.

[Lloyds] L↑

[Charlotte] A↑

Alice is paying HSBC, and Lloyds is paying Charlotte, but that unreasonably leaves HSBC better off and Lloyds worse off. There also needs to be a £5 transfer from HSBC to Lloyds, which is step 1b:

This is a single economic action:

HSBC→Lloyds {£5}: New debt.

[HSBC] L↑

[Lloyds] A↑

At this stage, this is just a promise by HSBC to pay Lloyds later (e.g. at the end of the day). But this promise to pay Lloyds £5 at a later time immediately decreases HSBC’s raw net worth2 (RNW) by £5, and increases Lloyds’s RNW by £5.

If we combine the 2 diagrams, we can see how Alice is paying Charlotte indirectly — via HSBC and Lloyds.

As far as Alice is concerned, she’s just transferred £5 to Charlotte. Most of the time, she doesn’t need to know that Charlotte has her account with a different bank, or that there is work going on behind the scenes in the banking system to make this happen.

Step 2 — Bank settlement

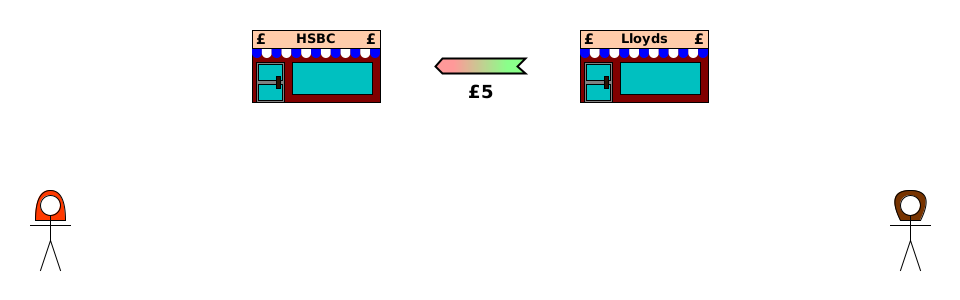

At a later time (maybe the end of the day), HSBC actually transfers £5 of its reserves (from its account at the BoE) to Lloyds.

Since HSBC and Lloyds both have accounts with the same bank (the BoE), this is just like how Alice paid Bob above. HSBC instructs the BoE to transfer reserves from the HSBC account to the Lloyds account.

HSBC→Lloyds {£5 (reserves)}: Transfer debt asset.

[HSBC] A↓

[Lloyds] A↑

But settling a debt isn’t just a single action. It’s a transaction, because in exchange, the creditor agrees that the debt is no longer owed. Here’s this other half of the transaction:

Lloyds agrees that HSBC no longer owes the debt.

Lloyds→HSBC {£5}: Write off debt.

[Lloyds] A↓

[HSBC] L↓

Again, we can combine the 2 diagrams, to see the whole transaction.

As you can see, settling a debt doesn’t involve a net transfer of RNW, because that transfer had already happened as soon as HSBC promised to pay Lloyds. The baseline assumption, when the debt was originally created, was that the promise would be kept, so when the promise is actually kept, it’s not a change from what was expected.3

Let’s finish with the whole scenario, right from the beginning.

This looks very similar to the scenario for just stage 1. The only difference is that instead of HSBC promising to pay Lloyds later, in this full scenario, HSBC has actually paid Lloyds by transferring reserves at the BoE from the HSBC account to the Lloyds account. When the reserves were transferred, HSBC’s promise to pay was written off by Lloyds, which cancelled out the original debt creation, as though the debt had never existed.

Summary

Paying someone who has an account at the same bank, when there’s enough in your account to pay, is simply a transfer of “deposit” debt assets.

If you don’t have enough in your account to make a payment, the bank might agree to let the payment go ahead anyway, as long as you promise to pay the bank later (and perhaps also pay interest or a fee).

Paying someone at another bank is indirect. You give up some of the deposits in your account; your bank promises to pay reserves to the other bank (which it later settles); and that other bank creates new deposits for the person you’re paying. The banking system hides the details of how this works from customers, and makes it look as though everyone is a customer of “one big bank”, as economist Perry Mehrling puts it.

This is only about half of the BTW study’s chapter on banking! I’ll continue in the next article.

Journals in the study show how different parties’ assets and liabilities change.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe (i.e. their assets minus their liabilities). It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them. If the idea is new to you, this article explains it with examples.

Breaking the promise would be a net transfer of RNW from the creditor to the debtor, since the debt would be written off, but no payment would be made in the opposite direction.

Great article Chris! Thank you!

Are you examine the Gov debt? I am finding the original paper excellent research, but the conclusions do not seem to match the paper. Let me know if you see any discrepancies.