The UK Exchequer (3)

Illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson study — Banking (2)

This is the third in a series of articles illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson (BTW) study “An Accounting Model of the UK Exchequer”. Here, we’ll continue looking at the UK banking system.

As always, I’ll be cross-referencing the BTW study by putting section numbers in square brackets.

Again, unfortunately this won’t fit in an email, so please follow the link (click on the article title) to see the whole article.

A simple model of the UK banking system (ctd) [4]

Net payment settlement [4.3]

In the last article, we looked at an inter-bank payment, where HSBC at first just promised to pay Lloyds later, and at the end of the day actually settled this debt by transferring reserves to the Lloyds account at the BoE.

But now suppose that a customer of Lloyds makes a payment to a customer of HSBC on the same day. What we’ll see is that only the difference (the net amount) needs to be settled, and the remainder of the debts just cancel each other out.

As before, Alice (“Customer 1”) and Bob (“Customer 2”) both bank with HSBC, and Charlotte (“Customer 3”) banks with Lloyds. In this scenario, Alice first pays Charlotte £5. Later on (but before the banks have settled) Charlotte pays Bob £5, and then also pays Alice £5.

Since there are so many steps to this scenario, I’m combining the two substeps for each inter-bank payment (part ‘a’ being the change to customers’ deposits, and part ‘b’ being the promise of the payer’s bank to pay the payee’s bank later).1

Step1 — Alice pays Charlotte

This is actually exactly the same as for scenario [4.2].

So, as before, step 1 consists of 3 actions (hence 3 arrows):

Alice→HSBC {£5 (deposit)}: Write off debt.

[Alice] A↓

[HSBC] L↓HSBC→Lloyds {£5}: New debt.

[HSBC] L↑

[Lloyds] A↑Lloyds→Charlotte {£5 (deposit)}: New debt.

[Lloyds] L↑

[Charlotte] A↑

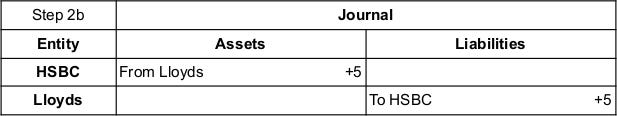

Step 2 — Charlotte pays Bob

Charlotte pays £5 to Bob.

This works exactly the same way as step 1, except in the opposite direction. Here are the 3 actions:

Charlotte→Lloyds {£5 (deposit)}: Write off debt.

[Charlotte] A↓

[Lloyds] L↓Lloyds→HSBC {£5}: New debt.

[Lloyds] L↑

[HSBC] A↑HSBC→Bob {£5 (deposit)}: New debt.

[HSBC] L↑

[Bob] A↑

Step 3 — Charlotte pays Alice

Charlotte pays Alice £5.

This is just like step 2. Here are the 3 actions:

Charlotte→Lloyds {£5 (deposit)}: Write off debt.

[Charlotte] A↓

[Lloyds] L↓Lloyds→HSBC {£5}: New debt.

[Lloyds] L↑

[HSBC] A↑HSBC→Alice {£5 (deposit)}: New debt.

[HSBC] L↑

[Alice] A↑

Step 4 — balance sheet

In the BTW study, step 4 is just showing everyone’s balance sheet at this point. This series is only showing the changes to balance sheets, so let’s move on to step 5.

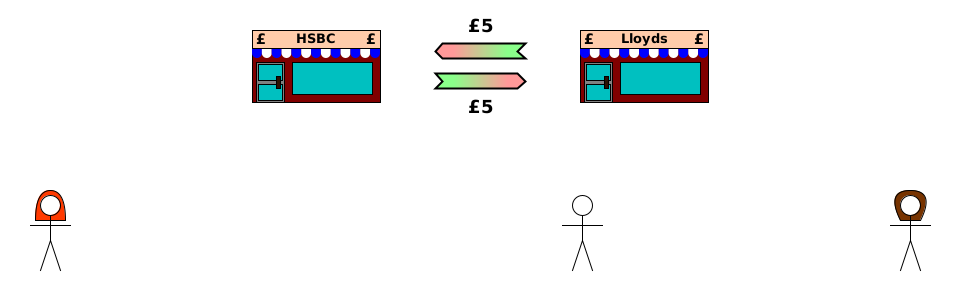

Step 5 — bank settlement

At end of day, as before, HSBC and Lloyds need to settle their debts to each other. HSBC has promised to pay Lloyds £5 (step 1), and Lloyds has promised to pay HSBC £10 (steps 2 and 3). There’s no point in HSBC transferring £5 of reserves to Lloyds, only for Lloyds to transfer it back again plus another £5. Instead, the smaller debt (in this case £5) is subtracted from both banks’ debts to the other (“netting off”), and then only the remaining £5 needs to be settled by a transfer of reserves.

Step 5a shows this netting off.

This is a transaction consisting of 2 actions:

Lloyds→HSBC {£5}: Write off debt.

[Lloyds] A↓

[HSBC] L↓HSBC→Lloyds {£5}: Write off debt.

[HSBC] A↓

[Lloyds] L↓

Steps 5b and 5c are the settlement of Lloyds’s remaining £5 debt to HSBC, and works just like we saw in section [4.2] where there was no netting. I’ve combined steps: 5b (where Lloyds transfers £5 of reserves to HSBC), and step 5c (where HSBC agrees that the debt is no longer owed).

The two actions are:

Lloyds→HSBC {£5 (reserves)}: Transfer debt asset.

[Lloyds] A↓

[HSBC] A↑HSBC→Lloyds {£5}: Write off debt.

[Lloyds] A↓

[HSBC] L↓

The whole settlement process, step 5, is like this:

HSBC agrees that Lloyds no longer owes it £10 in exchange for (1) Lloyds agreeing that HSBC no longer owes it £5, and (2) Lloyds transferring £5 of reserves to HSBC.

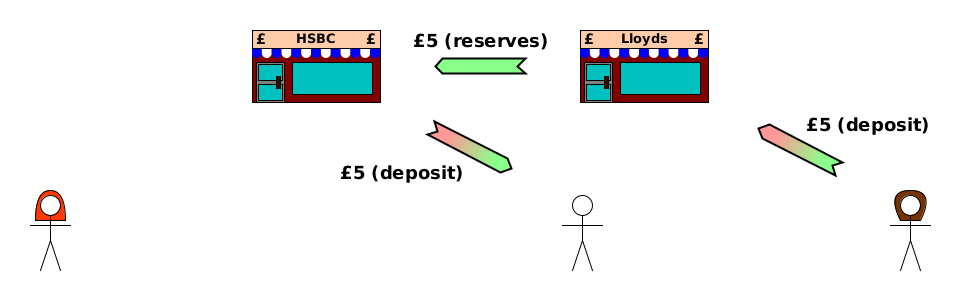

Steps 1-5

If we combine the whole scenario from step 1 to step 5, missing out any of the actions which cancel each other out, we’re simply left with this:

Unfortunately, because Alice’s payment to Charlotte was completely cancelled by Charlotte’s later payment to Alice, this example is essentially the same as scenario [4.2], and doesn’t clearly show the effect of netting, so I’ll add another example.

Additional netting scenario

This scenario is the same as that in section [4.3], except that instead of Charlotte paying £5 to Bob and £5 to Alice, she pays £10 to Bob.

Step 1 — Alice pays Charlotte £5

This is exactly as [4.3] step 1 above.

Step 2 — Charlotte pays Bob £10

This is like [4.3] step 2 above, except that £10 is transferred instead of £5.

Step 3 — Settlement

Settlement between HSBC and Lloyds is the same as in [4.3] step 5.

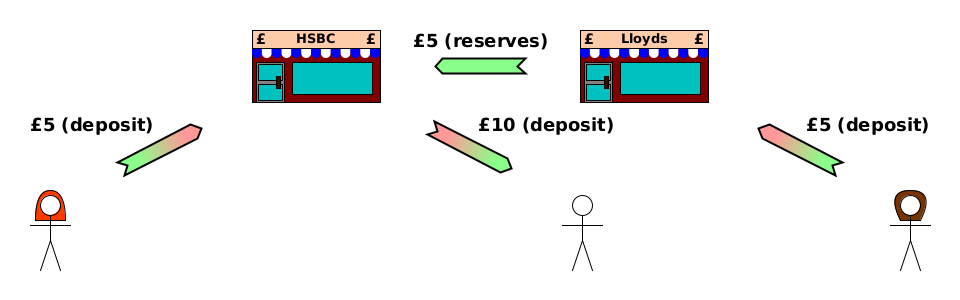

Steps 1-3 combined

When all 3 steps are combined, we get a more interesting picture than the previous complete scenario from section [4.3].

Like the previous scenario [4.3], this shows that even though there were £15 of payments between banks, only £5 of reserves actually had to be transferred. But what this example shows a little more clearly is that most of what HSBC was doing was only modifying its own internal accounts: decreasing Alice’s account balance by £5 and increasing Bob’s account balance by £10. The only economic interaction it needed with other banks was receiving the transfer of reserves from Lloyds to compensate for the difference.

Summary

When payments are made between accounts at different banks, there’s a process of “netting off” where the bank which owes more to the other pays the difference, and the remaining debts are simply cancelled, since they are equal and opposite. This means that banks typically don’t need to match deposits at 100% of reserves — or even anywhere near that level. (Of course, they still need enough assets to remain solvent, otherwise the deposits are promises which they can’t keep. But some of these assets can be ones which it’s difficult to sell quickly, such as loans or buildings).

There’s still another scenario in the chapter on banking! I’ll deal with that next time, and then move on to the chapter on government spending.

Payer = the one paying. Payee = the one being paid.