The UK Exchequer (4)

Illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson study — Banking (3)

This is the fourth in a series of articles illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson (BTW) study “An Accounting Model of the UK Exchequer”. Here, we’ll complete the section on the UK banking system.

As always, I’ll be cross-referencing the BTW study by putting section numbers in square brackets.

Again, unfortunately this won’t fit in an email, so please follow the link (click on the article title) to see the whole article.

A simple model of the UK banking system (ctd) [4]

Intraday credit [4.4]

In version 2 of scenario [4.1], we saw how Alice (“Customer 1”) could make a £5 payment to Bob (“Customer 2”) even if she didn’t have £5 in her HSBC account, as long as HSBC allowed her to use an overdraft facility.

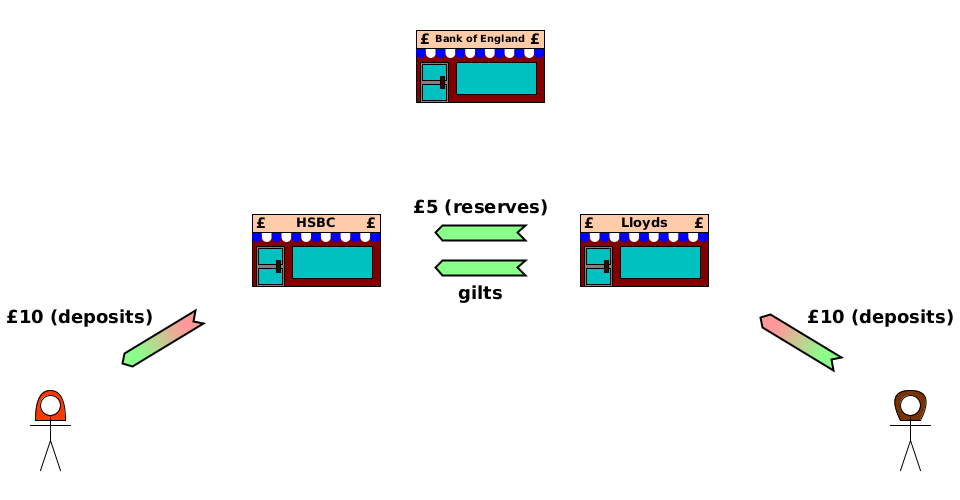

In this scenario, we’ll see something similar happening at the next level up, where Lloyds doesn’t have enough reserves to make a settlement payment to HSBC, but is able to make the payment by using a short-term overdraft facility offered by the Bank of England. Lloyds starts with £5 of reserves, but this isn’t enough to settle the debt which results from Charlotte paying £10 to Alice.

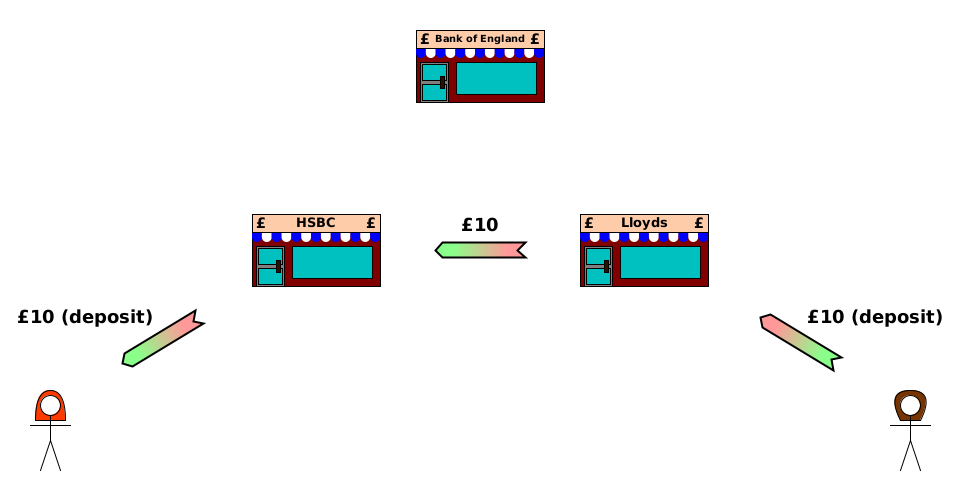

Step1 — Charlotte pays Alice

To start with, Charlotte at Lloyds pays £10 to Alice at HSBC, in the normal way we’ve seen in earlier scenarios.

Charlotte has £10 in her Lloyds account, so she has enough to make the payment.

This step is the usual 3 actions, as we’ve seen several times already. At this stage, Lloyds has only promised to pay HSBC later.

Charlotte→Lloyds {£10 (deposit)}: Write off debt.

[Charlotte] A↓

[Lloyds] L↓Lloyds→HSBC {£10}: New debt.

[Lloyds] L↑

[HSBC] A↑HSBC→Alice {£10 (deposit)}: New debt.

[HSBC] L↑

[Alice] A↑

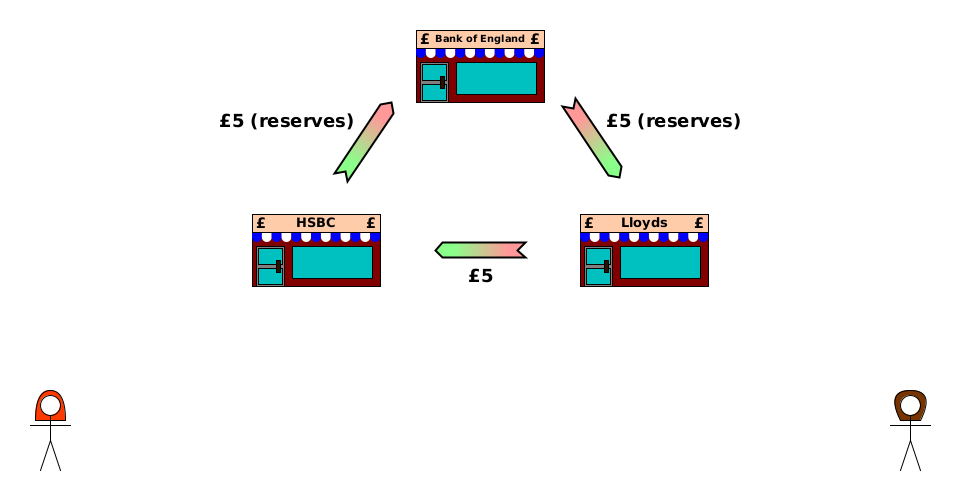

Step 2 — Settlement

Since Lloyds doesn’t have enough reserves at the BoE to transfer to HSBC, it must instead borrow from the BoE, similarly to how, in scenario [4.1] (version 2), Alice borrowed from HSBC to pay Bob when she didn’t have enough deposits to pay him.

There’s actually a numerical error in the BTW study at this point1. Step 2a shows Lloyds borrowing £10 from the BoE, but the initial balance sheet in step 0 showed that Lloyds actually started with £5 of reserves, which means it only needs to borrow £5 from the BoE to be able to pay £10 to HSBC. So that’s what I’ll show here. Future steps in the BTW study assume that this is what happened at this point.

The BTW study notes that Lloyds must pledge collateral (some of its assets, typically gilts i.e. government bonds) as security for the loan. That is, if it fails to repay the BoE later, the BoE can take possession of them. However, this doesn’t affect the journals, unless Lloyds actually fails to repay the BoE. (We’ll see an example of this later on).

There are 2 actions: the BoE creates new reserves for Lloyds, and Lloyds promises to pay the BoE later — the normal actions for lending.

BoE→Lloyds {£5 (reserves)}: New debt.

[BoE] L↑

[Lloyds] A↑Lloyds→BoE {£5}: New debt.

[Lloyds] L↑

[BoE] A↑

With the £5 of new reserves together with the £5 Lloyds started with, Lloyds can settle its £10 debt to HSBC.

Rather than showing a transfer of a debt asset (reserves) from Lloyds to HSBC, the journals represent it as a write off of Lloyds’s reserves at the BoE and the creation of new reserves for HSBC at the BoE. These are effectively the same thing: BoE ends up with its total reserve liabilities unchanged, Lloyds ends up with £10 fewer reserve assets, and HSBC ends up with £10 more reserve assets. The other side of the transaction — HSBC’s write off of the debt, agreeing that Lloyds no longer owes it — is shown exactly as before.

Lloyds→BoE {£10 (reserves)}: Write off debt.

[Lloyds] A↓

[BoE] L↓BoE→HSBC {£10 (reserves)}: New debt.

[BoE] L↑

[HSBC] A↑HSBC→Lloyds {£10}: Write off debt.

[HSBC] A↓

[Lloyds] L↓

As always, settlement doesn’t change anyone’s raw net worth2. Each party both gains £10 (arrow pointing towards them) and loses £10 (arrow pointing away from them). It’s just the composition of assets and liabilities which has changed.

If we combine both parts of step 2, we get the following diagram for the settlement of step 1:

Notice what’s going on between Lloyds and the BoE here:

Lloyds started with £5 of reserves,

It borrowed an extra £5 of reserves (promising to repay later), and

It then wrote off £10 of reserves.

Obtaining £5 of new reserves followed by writing off £5 of reserves cancel each out, which leaves just the two actions we see in the diagram: the promise to repay £5 (pink-to-green arrow) and the write off of the £5 of reserves which Lloyds started with (green-to-pink arrow).

This looks similar to step 2b by itself. The only difference is that half of the transfer from Lloyds to the BoE is Lloyds creating a new £5 debt instead of writing off an extra £5 of existing reserves as shown in step 2b.

Step 3 — balance sheet

In the BTW study, step 3 is just showing everyone’s balance sheet at this point. This series is only showing the changes to balance sheets, so let’s move on to step 4.

Step 4 — Lloyds borrows from another bank to settle debt to BoE

The BTW study tells us that Lloyds is apparently expected to settle its £5 debt to the BoE by the end of the day. If it doesn’t receive an inflow of reserves from another bank in the meantime3, it has to find another source.

A common way to do this is for Lloyds to borrow from another bank. In the BTW study’s example, it borrows from HSBC itself (which has a surplus due to the settlement of the payment from Charlotte to Alice). Step 4a shows this borrowing.

HSBC transfers £5 of reserves to Lloyds (again shown as an indirect transfer via the BoE), and in exchange, Lloyds promises to pay HSBC £5 the following day (plus interest, which the BTW study doesn’t show4).

HSBC→BoE {£5 (reserves)}: Write off debt.

[HSBC] A↓

[BoE] L↓BoE→Lloyds {£5 (reserves)}: New debt.

[BoE] L↑

[Lloyds] A↑Lloyds→HSBC {£5}: New debt.

[Lloyds] L↑

[HSBC] A↑

Apart from the minimal interest charged (not shown), again nobody’s RNW changes. HSBC is swapping £5 of reserves now for a promise to pay £5 later.

The final step in this scenario is Lloyds repaying its loan to the BoE.

This is the usual diagram for repayment. Each party writes off the other’s debt to it, undoing the original lending (step 2a).

Lloyds→BoE {£5 (reserves)}: Write off debt.

[Lloyds] A↓

[BoE] L↓BoE→Lloyds {£5}: Write off debt.

[BoE] A↓

[Lloyds] L↓

The write off by Lloyds of £5 of reserves undoes the creation of £5 of reserves for it by the BoE in step 4a. So the complete step 4 looks very similar to step 4a:

Steps 1-4

The complete scenario may seem a little strange. Here’s the summary:

[Step 1] Charlotte pays Alice, requiring Lloyds to promise to pay HSBC in future.

[Step 2] Lloyds borrows from the BoE to pay its debt to HSBC.

[Step 4] Lloyds borrows from HSBC to pay its debt to the BoE.

What’s the point of steps 2 and 4, when they seem to cancel each other out? I’d say it’s that step 2 could occur before the end of day, when there’s still a chance that Lloyds will receive a payment from another bank later in the day, which would allow it to settle its debt to the BoE at end of day without having to borrow from another bank. The original debt from Lloyds to HSBC is an integral part of the bank clearing system, and must be settled the same day, while the debt from borrowing in step 4 is the result of commercial overnight lending between the banks, in which HSBC has no obligation to be involved, and for which Lloyds must pay interest.

The other curious point about this scenario is that a debt between banks is left outstanding at the end of the day. Maybe the following day, Lloyds will gain more reserves than it loses, allowing it to settle the debt to HSBC. Or perhaps it will “roll over” the loan with HSBC’s permission, paying another day’s interest. Or it could even borrow from a third bank in order to pay its debt to HSBC, and hope to settle with that bank the day after. As long as there isn’t a continuous outflow of reserves for one bank, this is a satisfactory arrangement for everyone.

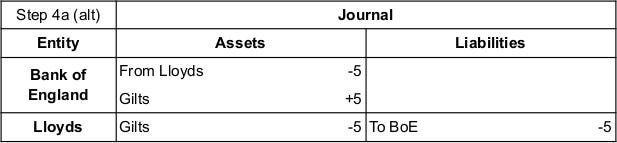

Alternative scenario — Lloyds uses gilts to repay BoE

Instead of borrowing from HSBC to repay the BoE, Lloyds could actually simply surrender the gilts which were collateral for the loan in step 2. The BTW study shows a step 4 for this alternative scenario. Step 4b (alt) also shows the BoE deciding to sell the gilts to another bank (in this case HSBC).

Step 4 (alt) — Lloyds surrenders gilts

Lloyds transfers some of its gilt assets to the Bank of England, instead of repaying the loan using reserves.

The journal shows £5 “worth” of gilts being transferred to the BoE. That doesn’t necessarily mean a government IOU for £5, because the prices of gilts can rise and fall, for reasons which I won’t go into here. Since the “current market price” is not what RNW represents, I’ll simply show this as “gilts” without specifying exactly what face value of gilts is transferred.

Lloyds→BoE {gilts}: Transfer debt asset.

[Lloyds] A↓

[BoE] A↑BoE→Lloyds {£5}: Write off debt.

[BoE] A↓

[Lloyds] L↓

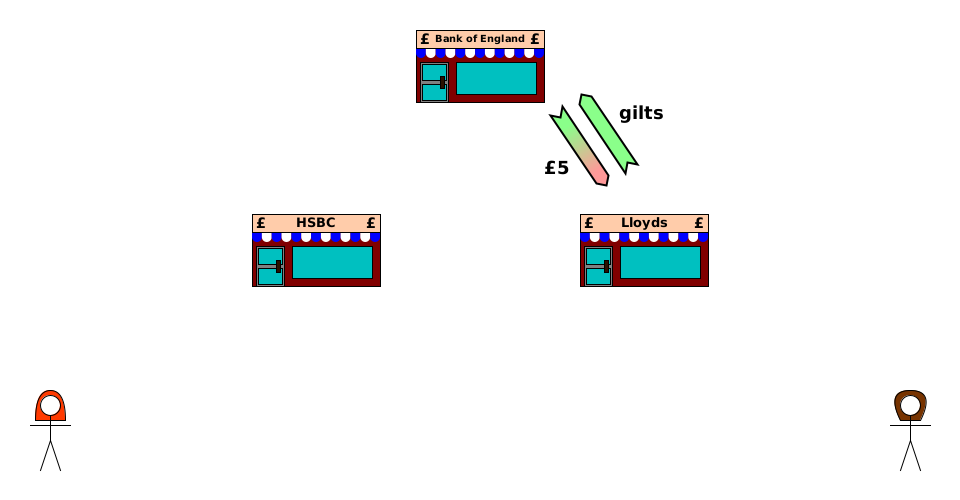

In the alternative scenario’s step 4b, the BoE sells the gilts to HSBC, which may prefer to have them than the reserves it received from Lloyds in step 2b.

Again, this is gilts with a “current market price” of £5. The face value is likely to be different.

HSBC→BoE {£5 (reserves)}: Write off debt.

[HSBC] A↓

[BoE] L↓BoE→HSBC {gilts}: Transfer debt asset.

[BoE] A↓

[HSBC] A↑

The complete alternative step 4 is just transfers round a circle, as are so many steps of these scenarios:

HSBC gives up the extra reserves. The BoE writes off Lloyds’s debt to it. And Lloyds transfers gilts to HSBC.

Steps 1-4 (alt)

Unlike the complete main scenario, the complete alternative scenario leaves no debts outstanding between the banks (other than the BoE, which still has reserve liabilities to HSBC):

Essentially, the main difference from normal bank settlement is that Lloyds transferred £5 “worth” of gilts instead of £5 of reserves for part of the amount (with the consent of HSBC).

Summary

A bank may not always have enough reserves to settle its obligations resulting from inter-bank transfers. It can obtain very short-term loans from the Bank of England to be able to make the transfers, but if it isn’t able to repay before the end of day, it needs to obtain reserves from a separate source, such as borrowing from another bank. Alternatively it can surrender the collateral from its BoE loan instead of repaying.

This is the end of the chapter on banking in the BTW study. It’s an important foundation for the study of the government’s own accounting, which we’ll start looking at in the next article.

In the meantime, if you’ve found this article interesting or informative, please click the ‘like’ button, and if you have any questions or comments, please leave them below: I’d be very interested to hear them. Thanks!

I’ve contacted Andrew Berkeley, one of the authors, who agrees this is an error.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe (i.e. their assets minus their liabilities). In general it is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them. (But in the BTW study, it’s typically just monetary units being added and subtracted). If the idea is new to you, this article explains it with examples.

There are many ways this could happen. For example, a customer of another bank could pay a customer of Lloyds. Or a customer of Lloyds could deposit cash.

Since interest on inter-bank lending is typically at a single-digit percent per year, an overnight loan of £1,000,000 would only involve an interest payment of ~£100-200, so it’s pretty insignificant.