The UK Exchequer (5)

Illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson study — Government Spending (1)

This is the fifth in a series of articles illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson (BTW) study “An Accounting Model of the UK Exchequer”. Having finished the chapter on the banking system, we now move on to government spending.

As always, I’ll be cross-referencing the BTW study by putting section numbers in square brackets.

Basics of Exchequer Spending [5]

According to the glossary in the BTW study, “The Exchequer” means:

Central government’s central financing arrangements, based on the Consolidated Fund and National Loans Fund, and managed by HM Treasury and the Bank of England.

The Consolidated Fund (CF) and the National Loans Fund (NLF) are two separate entities, each with its own assets and liabilities. We’ll see how they work over the coming weeks. As a starting point, it’s helpful to think of the CF as the part of government associated with spending and taxation, and the NLF as the part associated with the national debt.

The other main entity involved in government spending is the Government Banking Service (GBS). It acts like a bank for government departments, which have accounts with it1. But unlike for banks, the GBS’s equivalent of a bank’s reserve account — the Paymaster General (PMG) Drawing account — is almost entirely used for transfers out. Transfers in come from the CF, not from banks.

The basic process for government spending is a little involved. Every year, each government department requests authorisation from Parliament to spend particular amounts for particular purposes. If approved, the department is given a deposit2 in an account at the GBS, and it can spend this as needed, in a process which looks similar to the inter-bank transfers which we saw in chapter [4].

I’ll mention here that government balances in accounts at the BoE are referred to as “public deposits”, rather than “reserves”. It appears to me that the difference is just how they are categorised for reports.

If this introduction seems at all confusing, it should all become clear with the example scenarios.

Issues from the Consolidated Fund [5.1]

In this scenario, we imagine that the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has requested Parliament’s approval for its planned spending of £203. Once this has been authorised, the DWP is first allocated a £20 deposit at the GBS. At this stage, the GBS hasn’t received any public deposits in the PMG Drawing account — instead it just has the CF’s promise (called “supply funding”4) to increase the balance when it’s actually needed. The BTW study says that:

Such issues are typically made daily and are intended only to cover the forecasted short-term expenditure of particular departments and thereby reduce the need for unnecessary cash balances.

An issue like this is shown in step 2, at the point where the DWP will be making a £10 payment soon. The GBS calls on a part of its supply funding from the CF to top up the PMG Drawing account, in readiness to make the transfer.

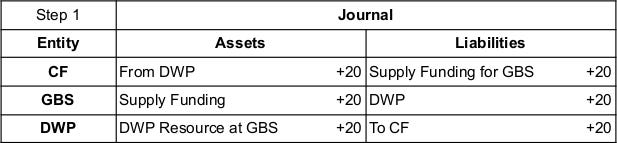

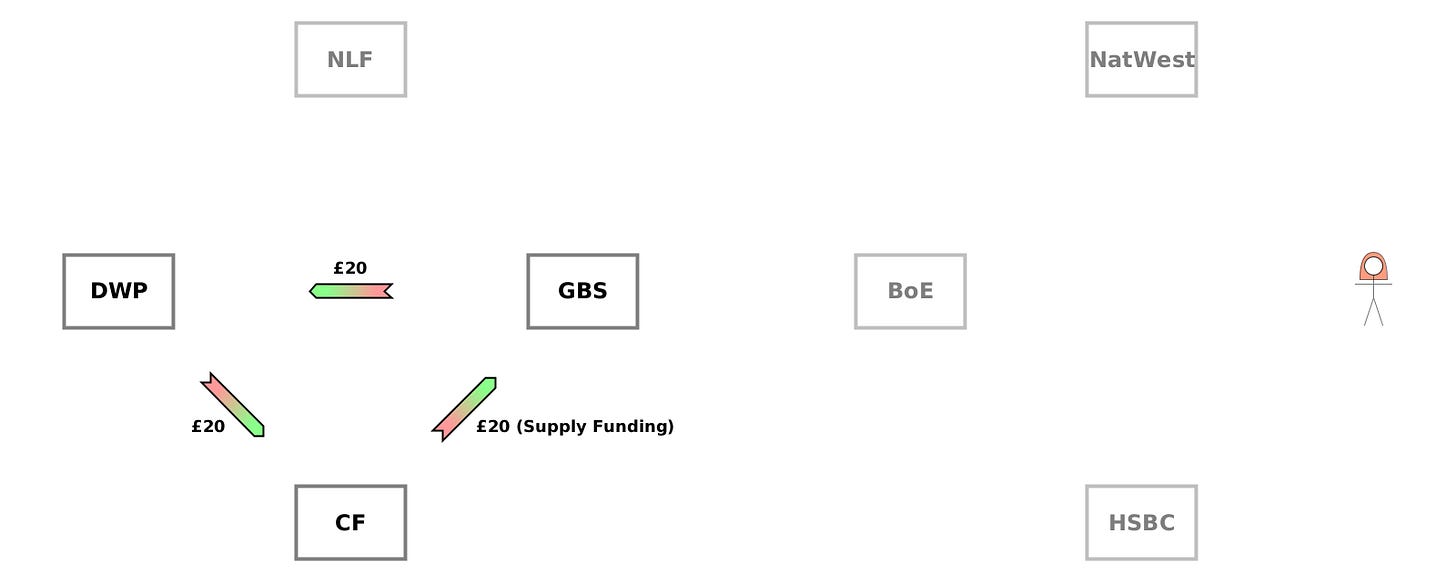

Step 1 — “vote funding”

This is where the DWP receives the £20 deposit in its account with the GBS. There is actually a loop of transfers, because the CF promises (“supply funding”) to make a transfer to the GBS’s PMG Drawing account on request (so that GBS can settle payments made by the DWP), and the DWP promises to pay back the CF if for some reason it ends up not spending the money for the purposes which were authorised5. (As we’ll see in future, this debt from the DWP to the CF is gradually written off as it makes its authorised payments).

There are 3 actions, with £20 being transferred around a loop.

CF→GBS {£20 (Supply Funding)}: New debt.

[CF] L↑

[GBS] A↑GBS→DWP {£20}: New debt.

[GBS] L↑

[DWP] A↑DWP→CF {£20}: New debt.

[DWP] L↑

[CF] A↑

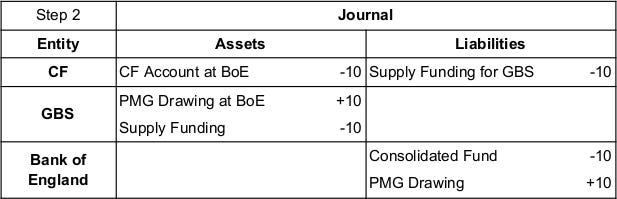

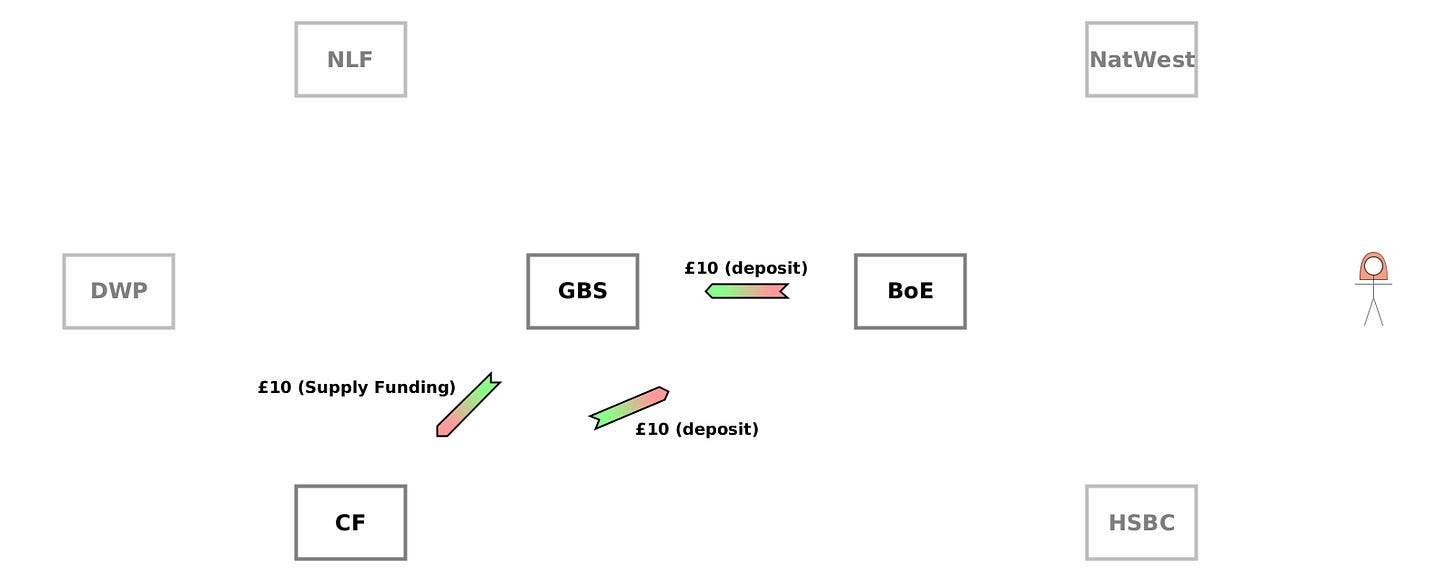

Step 2 — cash allocation

At this point, £10 is expected to be paid by the DWP soon, and so the GBS needs £10 in the PMG Drawing account, ready to settle the payment.

This step works a bit like a bank withdrawal. The CF had promised (“supply funding”) to pay the GBS £20, and GBS now wants £10 of this, so it gives up £10 of its supply funding in exchange for £10 of public deposits in its PMG Drawing account. The CF obtains the £10 from the BoE.

There’s actually an inconsistency in the BTW study at this point. The text (and the balance sheet in step 3) describes the CF essentially using an overdraft facility at the BoE i.e. its liabilities increase, while the journal below shows the CF’s assets decrease, as though it started with a positive balance (perhaps from tax receipts). But the effect is essentially the same: the CF’s raw net worth6↓ and the BoE’s RNW↑. In the diagram, I follow what the journal shows.

Again there are 3 actions, this time transferring £10 around a loop.

GBS→CF {£10 (Supply Funding)}: Write off debt.

[GBS] A↓

[CF] L↓CF→BoE {£10 (public deposit)}: Write off debt.

[CF] A↓

[BoE] L↓BoE→GBS {£10 (public deposit)}: New debt.

[BoE] L↑

[GBS] A↑

GBS has swapped £10 of supply funding from the CF for £10 of public deposits at the BoE.

Notice how nobody’s RNW has changed in the scenario so far. In each step, each party has been involved in 2 actions: one making its RNW↑ and one making its RNW↓ by exactly the same amount. That implies to me that nothing economically significant has happened yet. The various new debts which have been recorded in the accounts of the government and the BoE show what can be expected to occur in the short and medium term.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at the preparations made for a government department to be able to spend:

Each year, the department asks Parliament’s authorisation to spend for particular purposes in that year.

If approved, the department is allocated a deposit at the GBS, backed by “supply funding” from the CF — its promise to provide public deposits later.

When the actual spending is imminent, the GBS draws on its supply funding to receive public deposits in the PMG Drawing account at the BoE, which will be used to settle the department’s payments when they actually occur. The public deposits come from a transfer from the CF, which may involve the CF using its overdraft facility at the BoE — much like a bank does when it doesn’t have enough in its account to settle an inter-bank payment.

In the next article, we’ll look at the “sweeping process” which occurs at the end of each day.

These accounts are actually managed by NatWest, but any payments from them are settled by transfers from a GBS account at the BoE, as we’ll see.

The BTW study refers to this as a “Resource at GBS”.

In reality, the DWP is spending billions of pounds per year.

You don’t need to know why it’s called this to understand the accounting.

I expect an example of this this would be if more unemployed people find work than expected, so unemployment benefit payments are lower than anticipated.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe (i.e. their assets minus their liabilities). In general it is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them. (But in the BTW study, it’s typically just monetary units being added and subtracted). If the idea is new to you, this article explains it with examples.