The UK Exchequer (6)

Illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson study — Government Spending (2)

This is the sixth in a series of articles illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson (BTW) study “An Accounting Model of the UK Exchequer”. In the last article, we saw how a government department, whose proposed budget has been approved by Parliament, receives a deposit in the Government Banking Service (GBS), which it can then start spending. We also saw how the GBS itself receives “public deposits” (essentially the same as bank reserves) from the Consolidated Fund (CF) to settle these payments.

Here we’ll look at how the government’s accounts are tidied up at the end of each day, and restored the following morning. This tidying is known as the “end of day sweep”, and is why people often say (misleadingly?) that the CF’s balance is reset to zero every day.

As always, I’ll be cross-referencing the BTW study by putting section numbers in square brackets.

If you don’t have time to read the whole thing, I recommend just looking at the arrow diagrams to see how the sweep works.

Basics of Exchequer Spending (ctd) [5]

End of Day Accounting [5.2]

As we’ve seen, the Paymaster General (PMG) Drawing account works like the GBS’s equivalent of a bank’s reserve account with the Bank of England (BoE). It holds enough “public deposits” for the payments which government departments expect to make in the short term. The CF also has an account with the BoE, which could have a positive or negative balance.

At the end of each day, these balances are “swept” into the National Loans Fund (NLF). According to the BTW study:

The purpose of this sweep is to collect all balances of central bank money across the Exchequer into a single balance so that these can be reconciled with any claims by the Bank of England on the central funds (due to issuances).

The PMG balance is lent to the NLF overnight, where it’s considered a deposit, and it’s restored by a withdrawal in the morning. It’s as though the NLF is acting as a bank for the GBS.

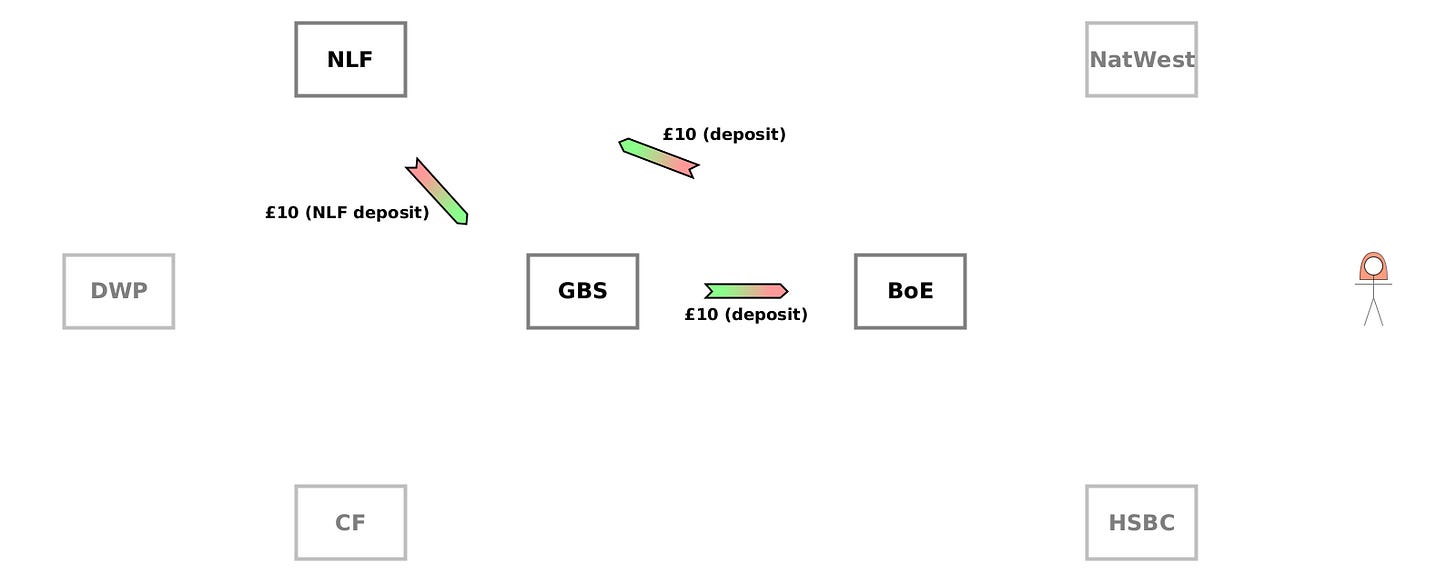

This scenario, showing the end of day sweep, continues the one from the previous article, where the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) first received a £20 deposit at the GBS, for which the GBS received £20 of “supply funding” from the CF. After this, the GBS exchanged £10 of this supply funding for £10 of public deposits at the BoE1. It’s this £10 of public deposits which is swept into the NLF.

Step 4 — End of day

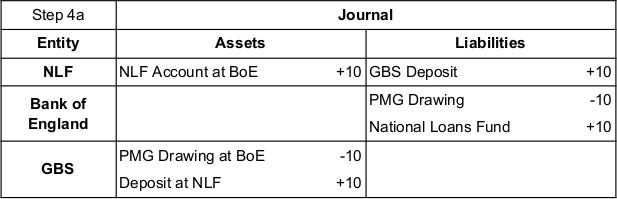

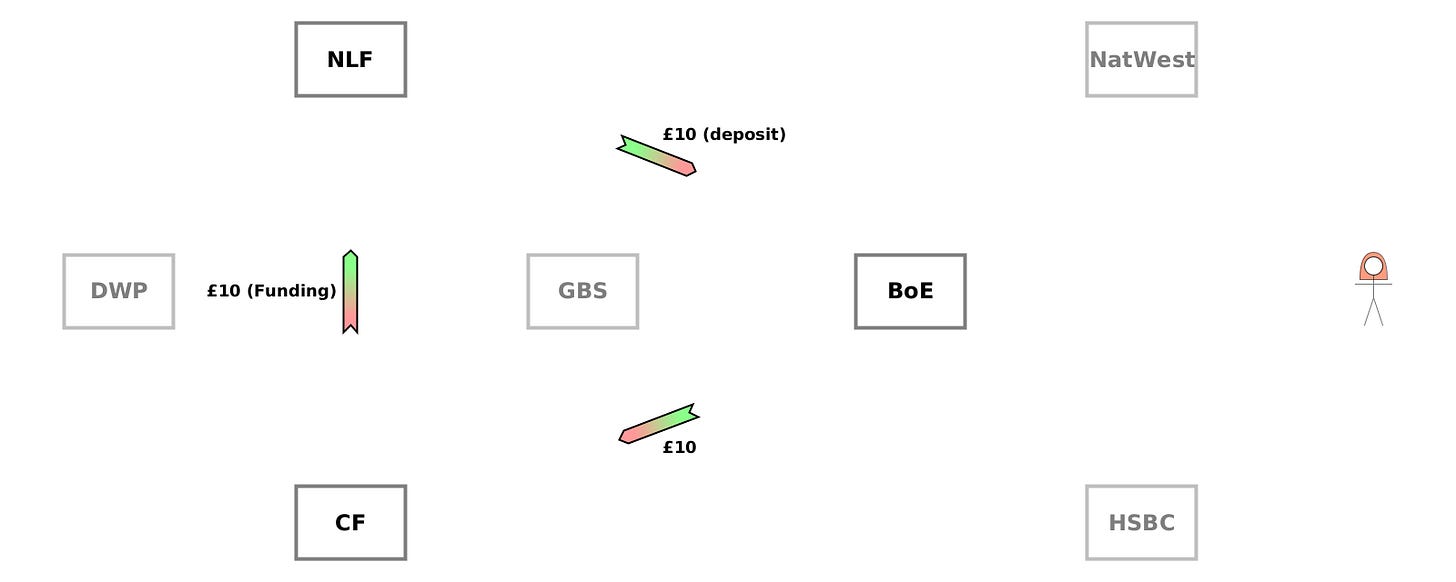

Step 4 is split into 2 parts. Step 4a shows the sweep from the PMG Drawing account into the NLF. Step 4b is the sweep of the CF account to the NLF.

Here’s the journal for the sweep from the PMG Drawing account:

There are 3 actions: two for a transfer of public deposits from the GBS to the NLF (via the BoE), and one for a promise by the NLF to repay the GBS the following day.

GBS→BoE {£10 (deposit)}: Write off debt.

[GBS] A↓

[BoE] L↓BoE→NLF {£10 (deposit)}: New debt.

[BoE] L↑

[NLF] A↑NLF→GBS {£10 (NLF deposit)}: New debt.

[NLF] L↑

[GBS] A↑

Notice that £10 is just going round a loop again. Each party both loses and gains £10 of raw net worth2 (RNW). According to the BTW study, the typical amount actually transferred from the PMG Drawing account in the end of day sweep is about £25 billion.

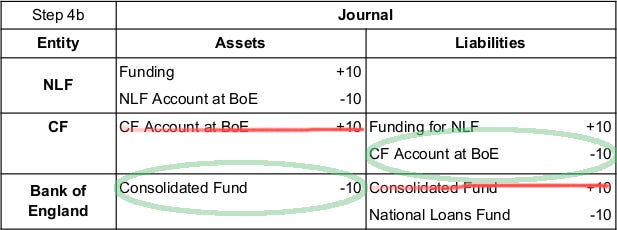

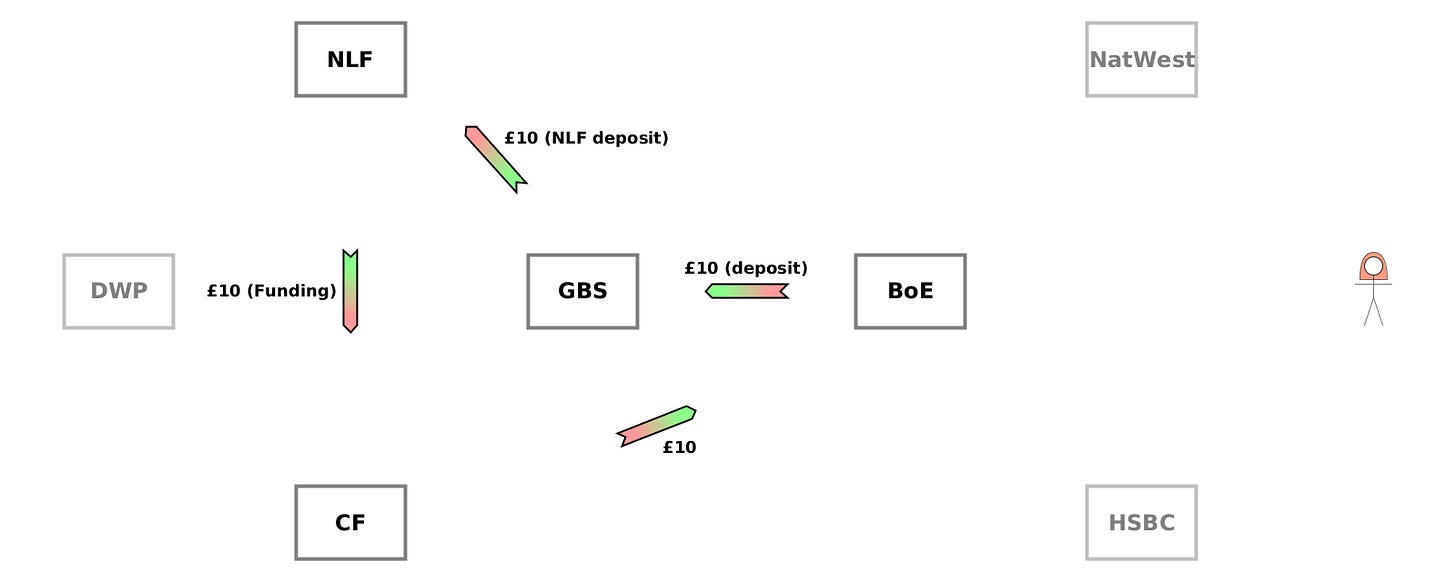

In step 4b, there’s another sweep — this time from the CF.

In the last article, there was an inconsistency in the BTW study between what the journal said and what the balance sheets before and after implied. The same is true here: the balance sheets in steps 3 and 5 imply that the CF’s liabilities decrease during this sweep, but the journal in step 4b shows that its assets increase. Unlike last time, I’ll show a diagram which matches the balance sheets. The reason is that the text in section [5.4] makes it clear that the aim of the sweep is to leave the CF with a zero balance at the BoE, and an increase to assets or liabilities is always moving away from zero. In practice, what really matters is that the CF’s balance with the BoE is transferred to the NLF, whether that balance was positive or negative.

The NLF is writing off the £10 public deposit asset at the BoE which it received from the GBS in step 4a, and the BoE is writing off its £10 asset owed to it by the CF in step 23.

NLF→BoE {£10 (deposit)}: Write off debt.

[NLF] A↓

[BoE] L↓BoE→CF {£10}: Write off debt.

[BoE] A↓

[CF] L↓CF→NLF {£10 (Funding)}: New debt.

[CF] L↑

[NLF] A↑

In this step, the NLF has transferred £10 to the CF (via the BoE). In exchange, the CF writes a new IOU (“Funding”) for £10 to the NLF.

In this particular scenario, both the NLF and the CF end up with a zero balance at the BoE. But this is just a special case, where their balances before the CF sweep happen to be equal and opposite. In general, the CF is always left with a zero balance, but the NLF isn’t.

Other sweeps

The BTW study tells us that the idea of the overnight sweep is to reconcile the Exchequer with the Bank of England by accumulating everything in a single place, and that there are other accounts at the BoE in government which are also swept into the NLF in the same way.

Note that the DWP account with the GBS is internal to government, and isn’t involved in the sweep. Only accounts held by the government at the BoE are swept into the NLF. The government departments themselves don’t need to be concerned with the sweep at all. As far as they are concerned, they have the same balance with the GBS as before.

Step 5 — balance sheet

In the BTW study, step 5 is just showing everyone’s balance sheet at this point. This series is only showing the changes to balance sheets, so let’s move on to step 6.

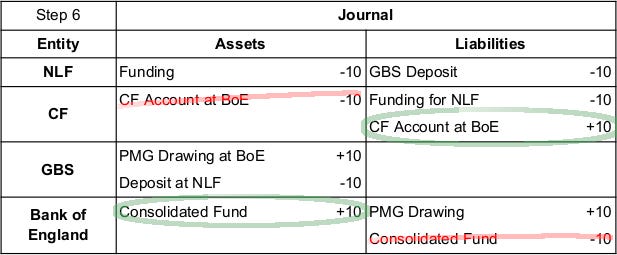

Step 6 — Start of day

At the start of the following day, the GBS “withdraws” its deposit at the NLF. If the NLF doesn’t have enough in its BoE account to transfer to the GBS, it obtains it from the CF (which borrows it from the BoE if necessary). In this case, the NLF’s balance is zero, and the GBS is withdrawing £10, so the NLF requests £10 from the CF.

Again, the balance sheets and the journals are inconsistent. Since the CF starts with a zero balance, I’ve adjusted the journal below to show the CF gaining a £10 liability (as implied by the balance sheets), rather than losing a £10 asset which it doesn’t currently have.

There are 4 actions here, transferring £10 of RNW around a loop:

The CF writes a new £10 IOU to the BoE,

The BoE creates a new £10 public deposit for the GBS (in the PMG Drawing account),

The GBS writes off its deposit at the NLF, and

The NLF writes off £10 of “Funding” from the CF.

NLF→CF {£10 (funding)}: Write off debt.

[GBS] A↓

[CF] L↓CF→BoE {£10}: New debt.

[CF] L↑

[BoE] A↑BoE→GBS {£10 (deposit)}: New debt.

[BoE] L↑

[GBS] A↑GBS→NLF {£10 (NLF deposit)}: Write off debt.

[GBS] A↓

[NLF] L↓

No changes to RNW

We still haven’t seen anything in chapter 5 where anyone’s RNW has changed. It’s all been transfers around a loop. As I said in the last article, that implies to me that nothing economically significant has happened yet. The various new debts which have been recorded in the accounts of the government and the BoE are showing what can be expected to occur in the short and medium term.

Summary

At the end of each day, balances in the several government accounts with the Bank of England, notably the Government Banking Service’s PMG Drawing account, are “swept” into the National Loans Fund, leaving them with zero balance at the BoE, but a deposit at the NLF. In this way, the NLF acts as a bank for the other parts of government. The Consolidated Fund’s balance is also swept into the NLF. This means that there is just a single account held by the government at the BoE which has a non-zero balance at the end of the day, which makes clear the position of the government with respect to the BoE.

In the morning, the PMG Drawing account balance at the BoE is restored by withdrawing its deposit from the NLF, which can call on the help of the CF if needed.

The sweep doesn’t affect individual government departments, whose account balances are with the GBS, and are left unchanged.

All of what we’ve seen so far in the government’s accounting is transfers of RNW around a loop, so nothing of economic significance has occurred yet. (We’ll see some actual changes in RNW in the next article when the DWP actually starts spending).

This is transferred from the CF’s account at the BoE. If it doesn’t have enough in the account, it can borrow from the BoE.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe (i.e. their assets minus their liabilities). In general it is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them. (But in the BTW study, it’s typically just monetary units being added and subtracted). If the idea is new to you, this article explains it with examples.

According to the balance sheets of step 1 and step 3, rather than the journal of step 2 itself, which showed the CF’s public deposit assets decreasing.

“This means that there is just a single account held by the government at the BoE which has a non-zero balance at the end of the day, which makes clear the position of the government with respect to the BoE”

Are you stating It’s the National Loans Fund (NLF), my understanding is the NLF also ends each day with a nil balance at BoE, any cash surpluses or deficits are offset by transfers to or from the DMA.

Awesome job Chris!

It seems to me the argument the authors are making is the ‘intra-day’ crediting of reserve accounts is an expansion of BoE liabilities and an expansion of the money supply, rather than the first step in a two step process of value transfer, which the BoE achieves via a Liability Swap between any two accounts in the BoE ledger. The authors are only giving us half the sandwich!

Forensically, I’ll concede every credit and every debit is a change in total outstanding BoE Liabilities, but if the end of day BoE balances with the Gov/Treasury show the same total outstanding BoE Liabilities, then there is no expansion of total Liabilities or reserve account credits to cover Treasury spending, and there is no net increase in reserves. The BoE is not creating money for the Treasury to spend.

If the BoE crediting the reserve accounts of banks of Gov payees is directly offset by Gov/Treasury reserves already on deposit in the NLA or simply any Treasury account on the BoE Ledger, then the payment is a BoE liability swap, and not a loan where the BoE ‘lends’ to Treasury, and not new net reserve creation. If there is no loan from the BoE to the Treasury, which we can determine by finding the correlated new BoE asset to the new BoE liability, if there is no increase in the BoE balance sheet or BS expansion, then there is no lending, and no new net reserves and no expansion of the money supply, the BoE is not creating new reserves ‘for’ the Treasury to spend, or lending new reserves to Treasury to spend, the BoE is transferring existing reserves from one Treasury account to the reserve account of the bank of the Gov payees.

Their argument is akin to saying when the coach sends in a substitute player on the pitch, and he taps and pulls off a player already on the field, was the team playing with twelve men?

Forensically, we can observe there were twelve men on the field, but this was a temporary state that resets back to 11 men.

In banking, we use the updated end of day state, where the BoE first debits for payments the appropriate Gov accounts where reserves are already on deposit, and only if the Treasury is short does the BoE lend those balances to Treasury on the Ways and Means facility, the Treasury Credit Line. If the definition of the BoE printing money is inter-day new Net Reserves, then the BoE has not created new reserves for the Treasury to borrow or spend in 17 years.