The UK Exchequer (7)

Illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson study — Government Spending (3)

This is the seventh in a series of articles illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson (BTW) study “An Accounting Model of the UK Exchequer”. In the last article, we saw the end-of-day “sweep”: each day, the balances of all the government’s accounts at the Bank of England (BoE) are transferred into the account of the National Loans Fund (NLF) for ease of reconciliation, and they are restored the following morning. (This is the origin of the idea that the Consolidated Fund’s (CF) balance is “reset” to zero each day).

In this article, we’ll finally see some actual government spending. The previous articles have all been preparation for understanding how this works. We’ll see that there are a lot of accounting entries, but that when we look at the changes to every party’s raw net worth1, government spending couldn’t be simpler.

As always, I’ll be cross-referencing the BTW study by putting section numbers in square brackets.

If you don’t have time to read the whole thing, I recommend just looking at the arrow diagrams.

Unfortunately, like some of the earlier articles in this series, this one is too long for Substack to send in full as an email, so please follow the link (click on the article title) to see the whole article.

Basics of Exchequer Spending (ctd) [5]

Payments of out the Exchequer [5.3]

There are three common means of making payments in the UK banking system: BACS, CHAPS and Faster Payments. A BACS payment takes 3 days to complete, similar to a cheque, while CHAPS is practically instantaneous2.

The BTW study says that BACS is the government’s preferred way to make payments, for reasons which I won’t go into here. In this article, we’ll see a BACS payment, and next time we’ll see a CHAPS payment.

BACS Payments [5.3.1]

As I mentioned in an earlier article, the Government Banking Service (GBS) acts like a bank for government departments. Its Paymaster General (PMG) Drawing account acts like a normal bank’s reserve account with the Bank of England. A payment from a government department to a recipient should look very familiar if you followed the earlier articles on banking in this series.

Before the BACS scenario of this section starts, the first step from an earlier article (see step 1 here) has already taken place:

The CF has provided GBS with £20 of supply funding3 ,

GBS has given the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) a £20 deposit, and

For now, DWP has promised to pay the £20 back to the CF if it doesn’t end up spending it for the authorised purpose. (We’ll see that the CF gradually writes off this last IOU as the department makes the authorised payments).

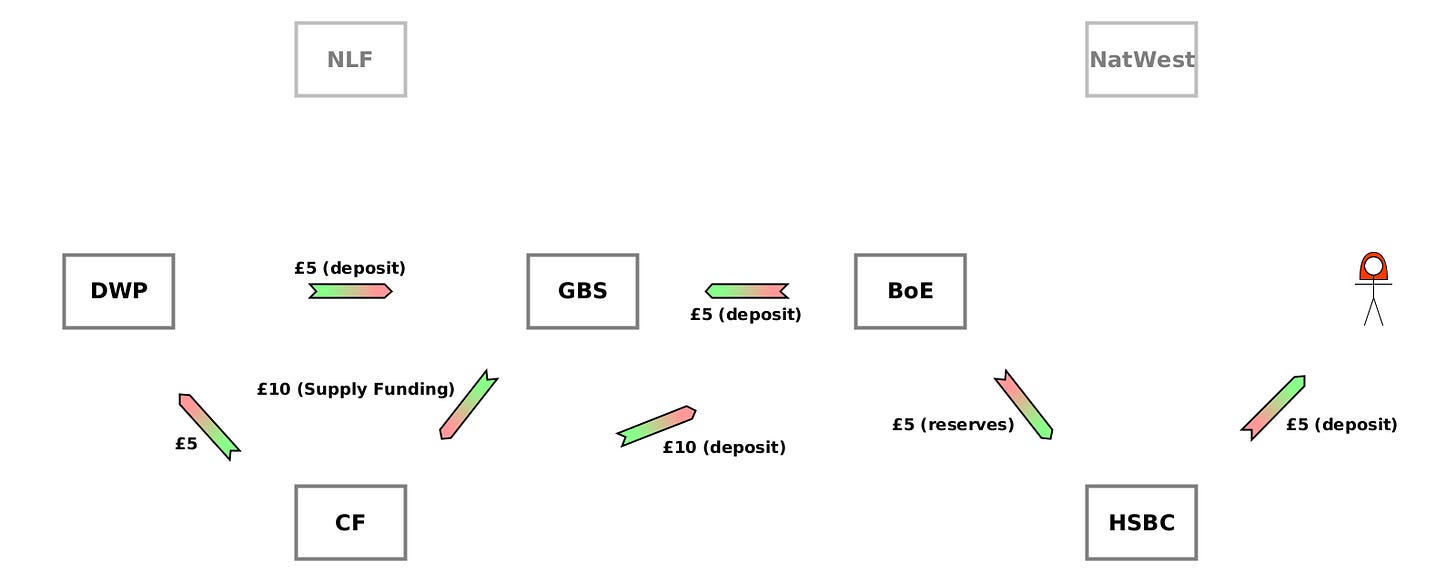

In this scenario, the DWP makes a £5 BACS payment to Alice (called “Recipient” in the journals). The way it works is that:

GBS draws on £10 of its £20 supply funding from the CF4;

DWP gives up £5 of its deposits with GBS;

Alice gains £5 of deposits from her bank, HSBC;

GBS promises to pay HSBC, and settles this later; and

CF writes off £5 of the debt owed to it by DWP5.

In the BTW study, the increase in Alice’s account at HSBC is split between step 1a (HSBC’s L↑) and step 3 (Alice’s A↑). In this article, I’m putting both parts into step 1a, because it seems far clearer to have both sides of the action (both halves of the same arrow) in the same step.

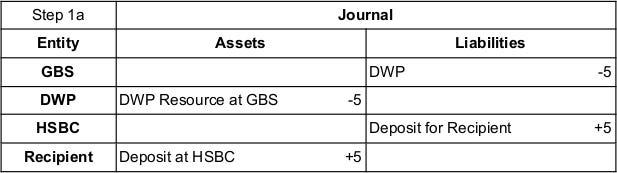

Step 1 — DWP pays Alice £5

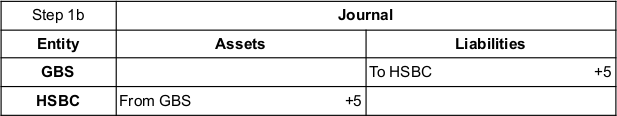

Step 1a is the decrease in DWP’s deposits with GBS and the increase of Alice’s deposits with HSBC. Step 1b shows GBS promising to settle with HSBC later. Together, this works just like the transfer from Alice to Charlotte in section [4.2] (see here).

Since this should be very familiar already, they’re combined into a single action diagram below.

Notice that, even though this is now the third article about chapter 5 of the BTW study, this is the very first diagram in which anyone’s RNW changes. (DWP’s RNW↓ and Alice’s RNW↑). Until this point, RNW was only being transferred around a loop. This is the first significant economic activity of government spending. DWP is transferring £5 of its RNW to Alice indirectly, via GBS and HSBC.

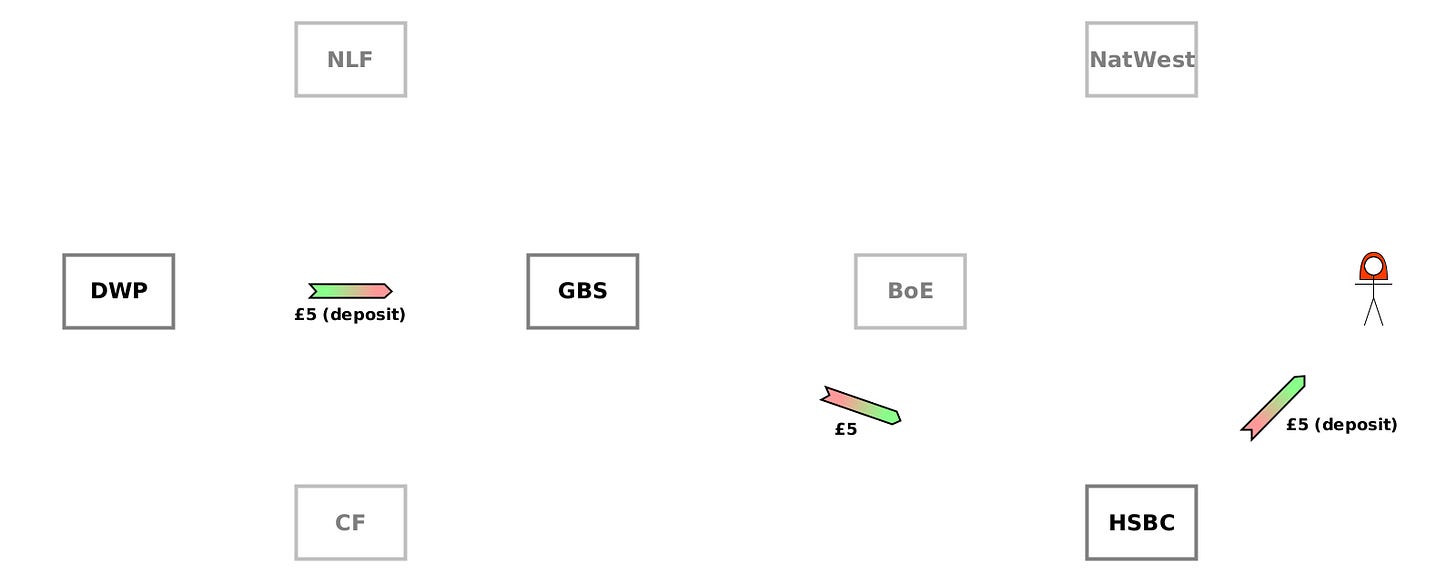

Notice too that the structure of the diagram is exactly the same as section [4.2] step 1 (see below), where Alice (banking with HSBC) paid Charlotte (banking with Lloyds):

The payer loses a deposit with their “bank”

The recipient gains a deposit with their bank

The payer’s “bank” promises to pay the recipient’s bank.

Comparing the two diagrams, we can see that GBS is performing the same role as a private sector bank.

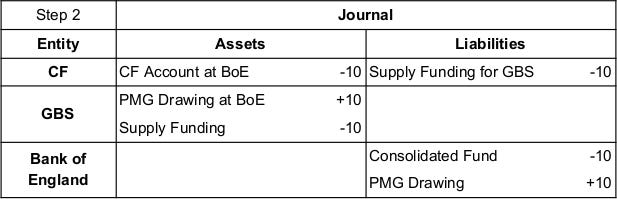

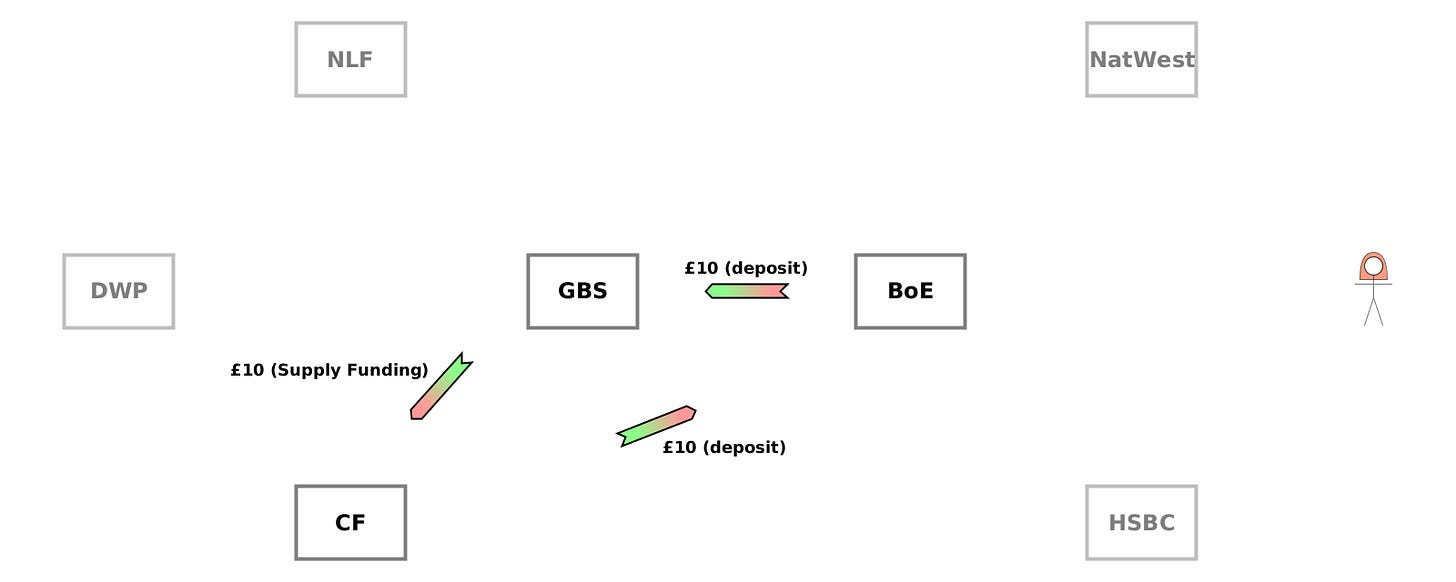

Step 2 — cash allocation

So far, GBS has only promised to pay HSBC. It will need something in the PMG Drawing account to transfer to HSBC to actually make the payment. In step 2, as we saw in step 2 of section [5.1], the CF transfers some of the balance in its account at the BoE (borrowing it from the BoE if it doesn’t have enough).

Once again, there’s an inconsistency in the BTW study at this point. The balance sheets in steps 0 and 5 imply that the CF has essentially used an overdraft facility at the BoE i.e. its liabilities increase, while the journal below shows the CF’s assets decrease, as though it started with a positive balance (perhaps from tax receipts). But the effect is essentially the same: the CF’s RNW↓ and the BoE’s RNW↑. The arrow diagram below follows what the journal shows.

There are 3 economic actions. Two for the transfer of £10 from the CF to GBS’s PMG Drawing account (via the BoE), and one for GBS writing off £10 of the CF’s “supply funding” debt, since the CF has now kept its promise.

You can think of this as the CF settling £10 of the £20 “supply funding” debt — the promise it made to the GBS earlier.

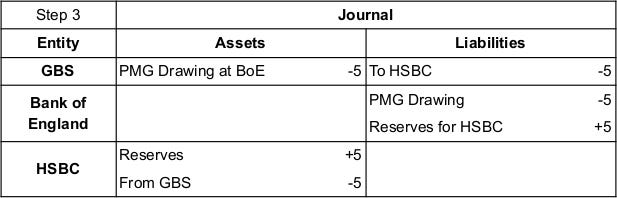

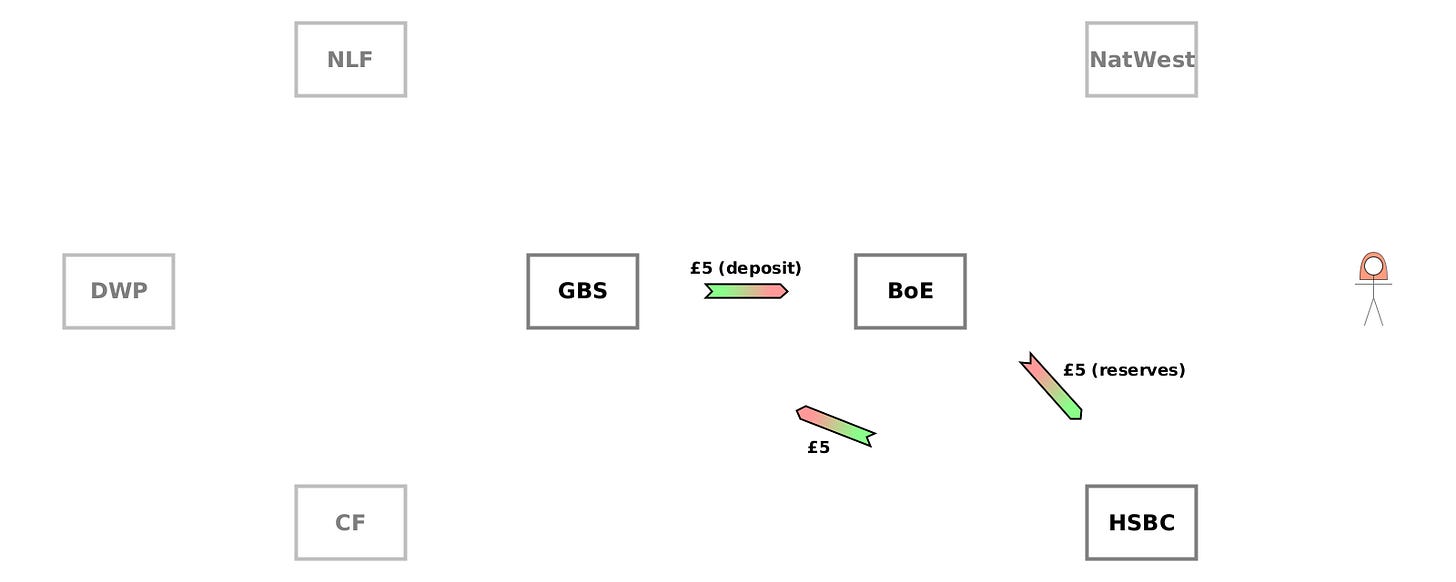

Step 3 — GBS settles debt to HSBC

So far, the GBS has only promised to pay £5 to HSBC later. At a point later in the day, GBS actually settles its debt by making a transfer between their accounts at the BoE. In exchange, HSBC agrees that GBS no longer owes the debt.

Note that the step 3 journal in the BTW study shows Alice gaining a deposit at HSBC, but in this article that’s been moved to step 1a above, to be with the other entry for the same economic action.

This is another settlement with 3 economic actions. Two for the transfer of £5 from the GBS PMG Drawing account to HSBC (via the BoE), and one for HSBC writing off GBS’s promise to settle the debt resulting from DWP’s earlier £5 payment to Alice.

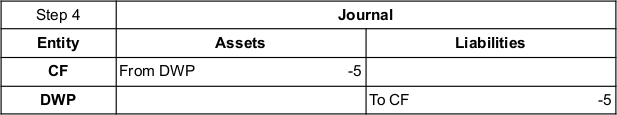

Step 4 — CF writes off £5 of DWP debt

As mentioned above, before the start of this scenario, DWP had promised to pay its allocated £20 back to the CF if it didn’t end up spending it for the authorised purpose. But now that the DWP has spent £5 of it, the CF writes off £5 of that debt owed to it by the DWP.

This is just a single economic action:

Again, this isn’t RNW being transferred around a circle, so you could say it’s economically significant. But with it being a transfer within government, it’s much less significant than step 1, which was a transfer of RNW from the government (specifically the DWP) to Alice.

Steps 1-4

If we combine all the steps, two actions cancel each other out: GBS promising to pay HSBC £5 (in step 1) and HSBC writing off that debt when it has been settled (in step 3). Also, the transfer of £10 from BoE to GBS (in step 2) is partially offset by a transfer of £5 from GBS to BoE (in step 3). This leaves the following diagram, which might seem complicated at first:

But even though the exact assets and liabilities have changed for each party, if you look at only the total change to their RNW, you’ll see that almost all are unchanged6:

DWP: + £5 - £5 = 0

GBS: + £5 + £5 - £10 = 0

BoE: + £10 - £5 - £5 = 0

HSBC: + £5 - £5 = 0

Only CF’s and Alice’s RNWs have changed:

CF: + £10 - £5 - £10 = - £5

Alice: + £5

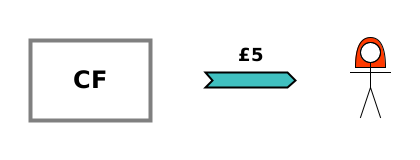

In other words, when we’re only looking at changes to RNW, without considering the specific assets and liabilities which make it up, government spending simplifies to this:

The blue arrow represents a transfer of RNW without being specific about how that transfer takes place. From the point of view of RNW, government spending is nothing more complicated than a transfer of RNW from the CF to the recipient.

Summary

In previous articles, we’ve seen the preparation work done to enable a government department to spend. Here, we’ve seen that the spending is just like a bank transfer within the private sector. The Government Banking Service (GBS) acts like a bank for the government department, and its Paymaster General (PMG) Drawing account is equivalent to a bank’s reserve account at the Bank of England (BoE).

When a government department makes an authorised payment, that reduces the amount which it owes back to the Consolidated Fund (CF) for any authorised spending which hasn’t taken place.

While the combination of preparation work and payment may seem complicated when we look at all of the changes to each party’s assets and liabilities, it’s just made up of smaller steps which make sense in their own right. And additionally, if we simply look at the changes to everyone’s raw net worth (RNW), most of the changes cancel each other out, and government spending is simply a transfer of RNW from the CF to the recipient. It couldn’t be simpler.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe (i.e. their assets minus their liabilities). In general it is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them. (But in the BTW study, it’s typically just monetary units being added and subtracted). If the idea is new to you, this article explains it with examples.

From my personal experience, when we were buying a house, we had to pay the seller by CHAPS. The seller presumably didn’t want to hand over the house keys and not find out until days later whether they’d actually been paid.

The CF’s promise to transfer money to the PMG Drawing account shortly before the department is due to spend it.

Presumably, GBS expects another £5 payment to be made soon, but that isn’t part of this scenario.

DWP no longer owes the money back to the CF, because it spent it in the way it was supposed to.

Arrows pointing to each party show the increases to their RNW, and arrows pointing away from them show the decreases to their RNW. The total change is the difference between the two.