The UK Exchequer (8)

Illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson study — Government Spending (4)

This is the eighth in a series of articles illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson (BTW) study “An Accounting Model of the UK Exchequer”. In the last article, we saw a government department actually paying a member of the public using a BACS transfer, and how this was essentially the same process as a payment by bank transfer in the private sector; the Government Banking Service (GBS) plays the part of a bank for government departments. We also saw that, when we consider just the changes to raw net worth1, the payment is essentially nothing more than an indirect transfer of RNW from the Consolidated Fund (CF) to the recipient.

In this article, we’ll see the same payment, but using a faster CHAPS transfer, which works in a slightly different way. But, as we’ll see, the outcome is the same.

As always, I’ll be cross-referencing the BTW study by putting section numbers in square brackets.

If you don’t have time to read the whole thing, I recommend just looking at the arrow diagrams, and especially noting whose RNW changes at each stage2.

Basics of Exchequer Spending (ctd) [5]

Payments of out the Exchequer (ctd) [5.3]

CHAPS Payments [5.3.2]

The BTW study tells us that CHAPS payments can’t be settled directly from the Exchequer. Instead, they are settled from the reserve account of the bank which provides the banking services to the GBS (NatWest at the time of the study), which receives a transfer from the GBS’s Paymaster General (PMG) Drawing account to compensate it.

In essence, the difference between this and a BACS payment (as we saw in the last article) is that the transfers from the PMG Drawing account to the recipient’s bank’s reserve account are indirect (via NatWest), rather than direct.

Let’s take a look at the detail from the journals.

This scenario starts in the same place as the BACS scenario from section [5.3.1], where the following has already happened:

The CF has provided GBS with £20 of supply funding3 ,

GBS has given the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) a £20 deposit, and

For now, DWP has promised to pay the £20 back to the CF if it doesn’t end up spending it for the authorised purpose. (The CF gradually writes off this last IOU as the department makes the authorised payments).

And, like the BACS scenario, the aim is for DWP to pay £5 to Alice, who banks with HSBC.

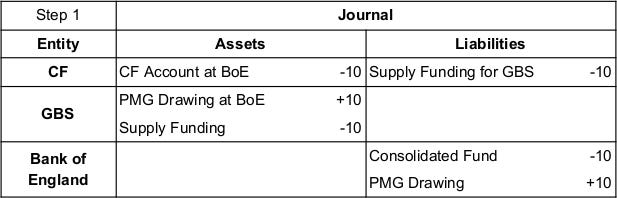

Step 1 — cash allocation

This is the same as step 2 of the BACS payment, so what follows is almost a repeat of that.

GBS will need something in the PMG Drawing account to transfer to HSBC to actually settle the payment. In step 1, as we saw in step 2 of section [5.1], the CF transfers some of the balance in its account at the BoE (borrowing it from the BoE if it doesn’t have enough).

Once again, there’s an inconsistency in the BTW study at this point. The balance sheets in steps 0 and 4 imply that the CF has essentially used an overdraft facility at the BoE i.e. its liabilities increase, while the journal below shows the CF’s assets decrease, as though it started with a positive balance (perhaps from tax receipts). But the effect is essentially the same: the CF’s RNW↓ and the BoE’s RNW↑. The arrow diagram below follows what the journal shows.

There are 3 economic actions. Two for the transfer of £10 from the CF to GBS’s PMG Drawing account (via the BoE), and one for GBS writing off £10 of the CF’s “supply funding” debt, since the CF has now kept its promise.

You can think of this as the CF settling £10 of the £20 “supply funding” debt — the promise it made to the GBS earlier.

Notice that, as with all settlement, nobody’s RNW has a net change: each party’s RNW both decreases and increases by £10. So this is not economically significant.

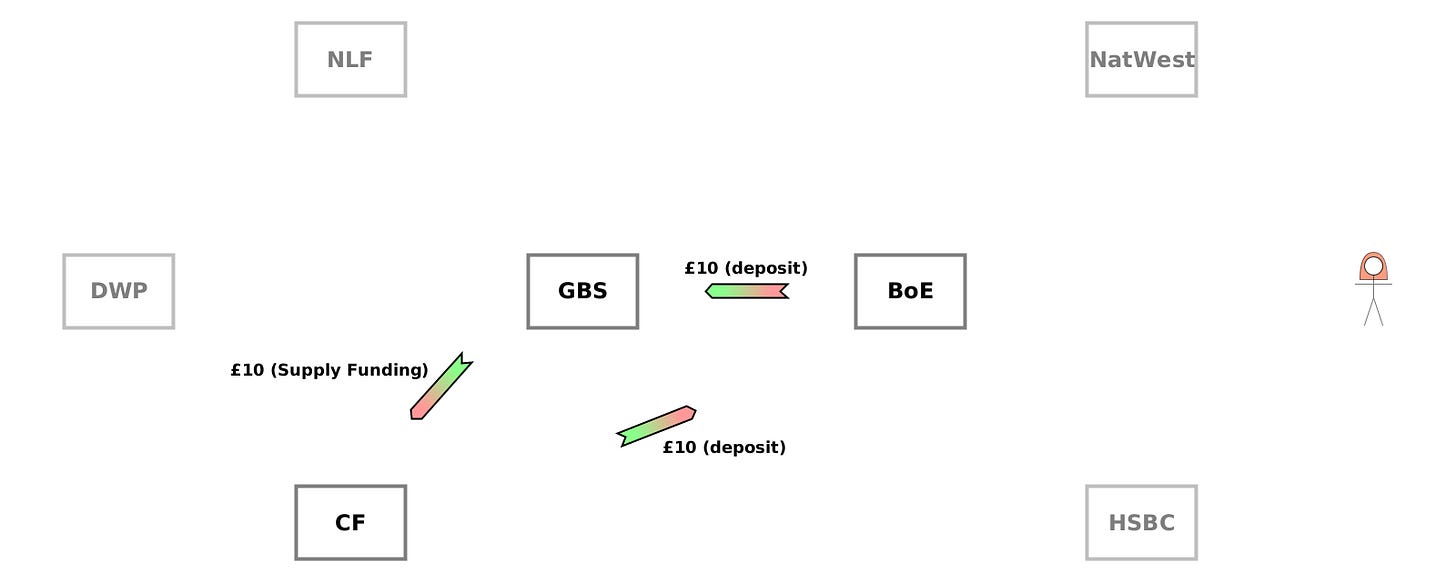

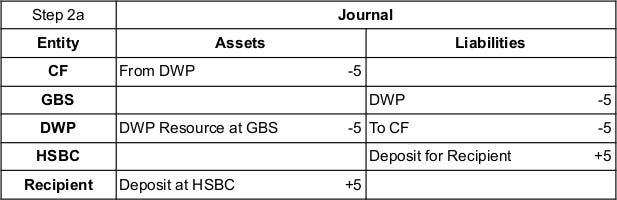

Step 2 — payment to Alice

Step 2 is split into two parts in the BTW study, but I’m combining them here, since it should be a familiar pattern of actions by now:

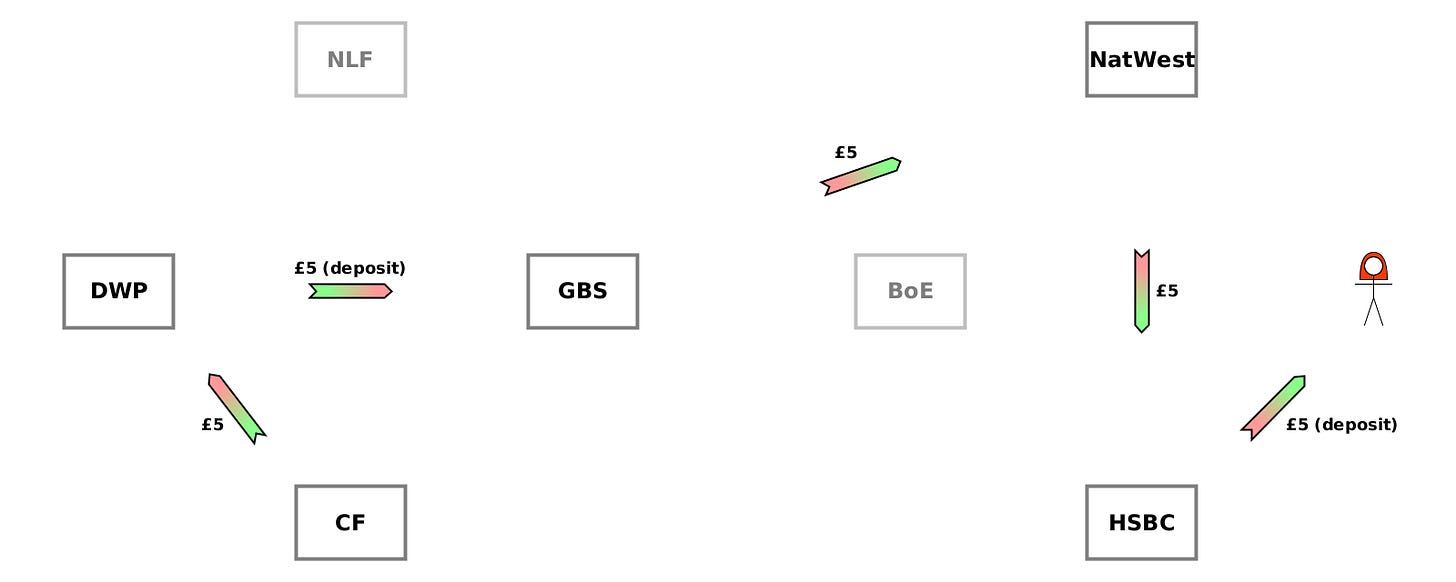

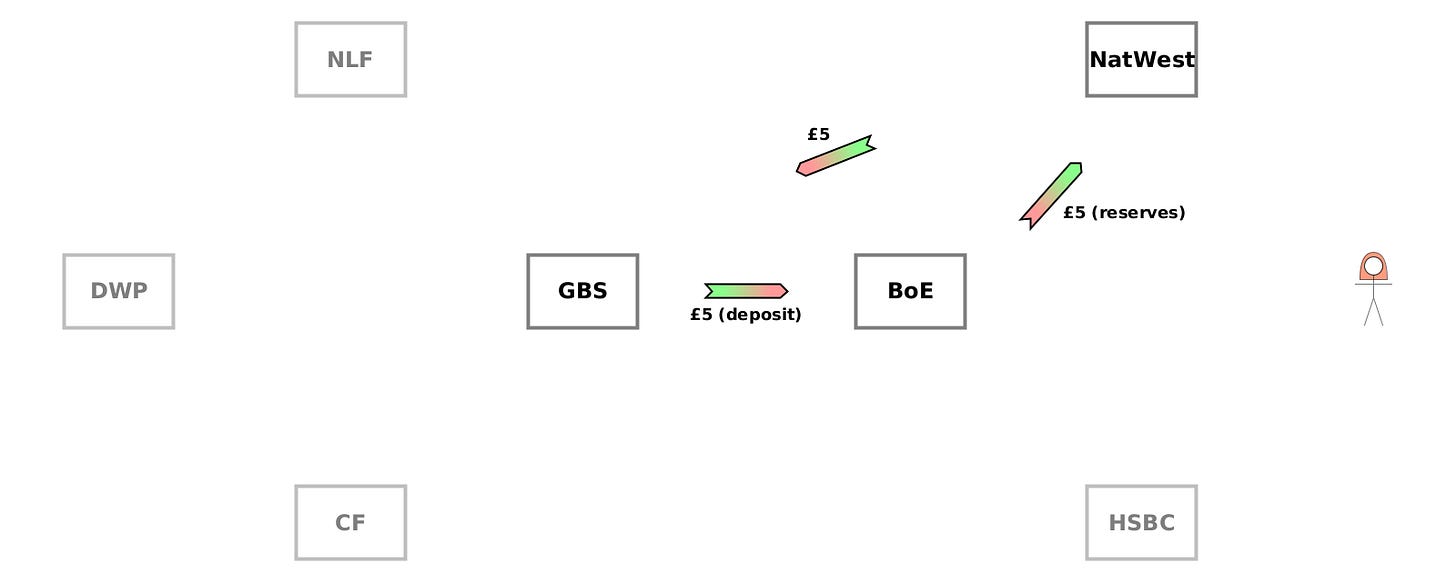

DWP transfers £5 to Alice (indirectly, via GBS, NatWest and HSBC).

CF writes off £5 of the debt owed to it by DWP4.

There are 5 actions which form a chain of transfers: CF → DWP → GBS → NatWest → HSBC → Alice.

The difference compared to a BACS payment is just that GBS promises to pay NatWest, and NatWest promises to pay HSBC, rather than GBS promising to pay HSBC directly.

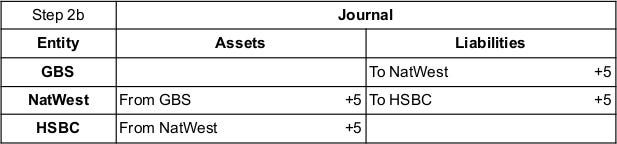

Step 3 — settlement

The final part of the scenario is settlement of the two inter-bank debts. Step 3a shows the settlement of the debt from NatWest to HSBC, and step 3b shows the settlement of the debt from GBS to NatWest. This should be very familiar by now.

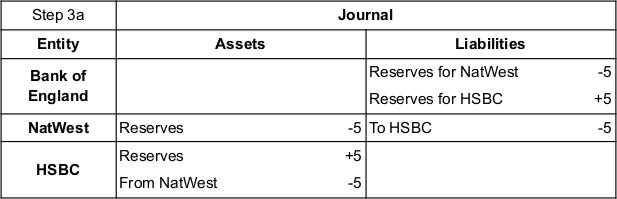

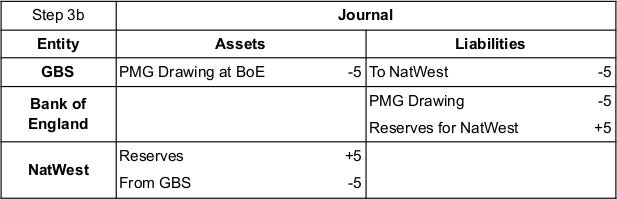

First step 3a:

This is the usual 3 actions for bank settlement. NatWest transfers reserves to HSBC (via the BoE). And in exchange HSBC agrees that NatWest no longer owes the debt.

As always, when settlement involves paying what was owed, there’s no net change to anyone’s RNW. Each party’s RNW both increases by £5 and decreases by £5.

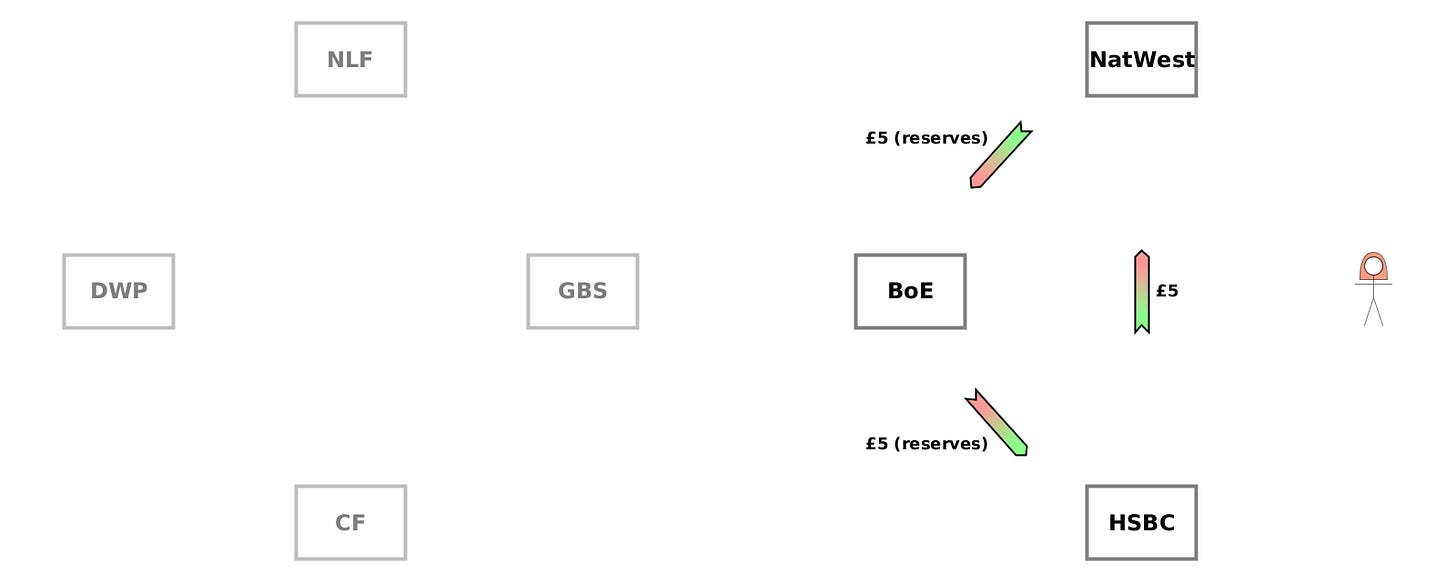

Now step 3b:

This is the same 3-action structure as step 3a. The payment is made from GBS to NatWest indirectly via the BoE, and NatWest agrees that GBS no longer owes the debt.

The only difference is that the arrow from GBS to BoE is labelled “deposit”, because government balances at the BoE are known as “public deposits” rather than “reserves”. I’m not aware of any practical difference between public deposits and reserves — I believe they’re just categorised differently.

Again, being settlement, RNW is just transferred around a loop, so there’s no net change to anyone’s RNW.

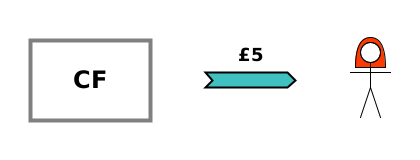

Steps 1-4

Unsurprisingly, given the similarity to the BACS payment from the previous article, all of this activity amounts to the same thing. In almost every case, there’s no net change to any party’s RNW in the transactions. The only exceptions are CF and Alice in step 2, where CF’s RNW↓ £5 and Alice’s RNW↑ £5. In other words, the whole scenario simplifies to a transfer of £5 of the CF’s RNW to Alice:

Summary

The only significant difference between a BACS payment and a CHAPS payment is that the transfer from the Government Banking Service (GBS) to the recipient has an extra link in the chain: the provider of the GBS services (NatWest at the time of the BTW study) receives payment from GBS, and makes a payment to the recipient’s bank, instead of GBS paying the recipient’s bank directly.

When we look at just the changes to everyone’s Raw Net Worth (RNW), we see that government spending for a CHAPS payment is as simple as for a BACS payment: the Consolidated Fund (CF) transfers £5 to the recipient.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe (i.e. their assets minus their liabilities). In general it is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them. (But in the BTW study, it’s typically just monetary units being added and subtracted). If the idea is new to you, this article explains it with examples.

Arrows pointing towards a person/entity show their RNW↑, and arrows pointing away from them show their RNW↓. It’s extremely common for these to net to zero in the scenarios we’re examining. Pay particular attention to anywhere they don’t.

The CF’s promise to transfer money to GBS’s PMG Drawing account shortly before the department is due to spend it.

DWP no longer owes the money back to the CF, because it spent it in the way it was supposed to.