The UK Exchequer (9)

Illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson study — Government Spending (5)

This is the ninth in a series of articles illustrating the Berkeley, Tye and Wilson (BTW) study “An Accounting Model of the UK Exchequer”.

This article illustrates section [5.4], which combines everything we’ve seen so far on government spending:

Supply funding

Cash allocation

Spending

End-of-day sweep1

We’ve been through all these steps in earlier articles, so I won’t labour the details. Instead, I’d like you to focus on two things:

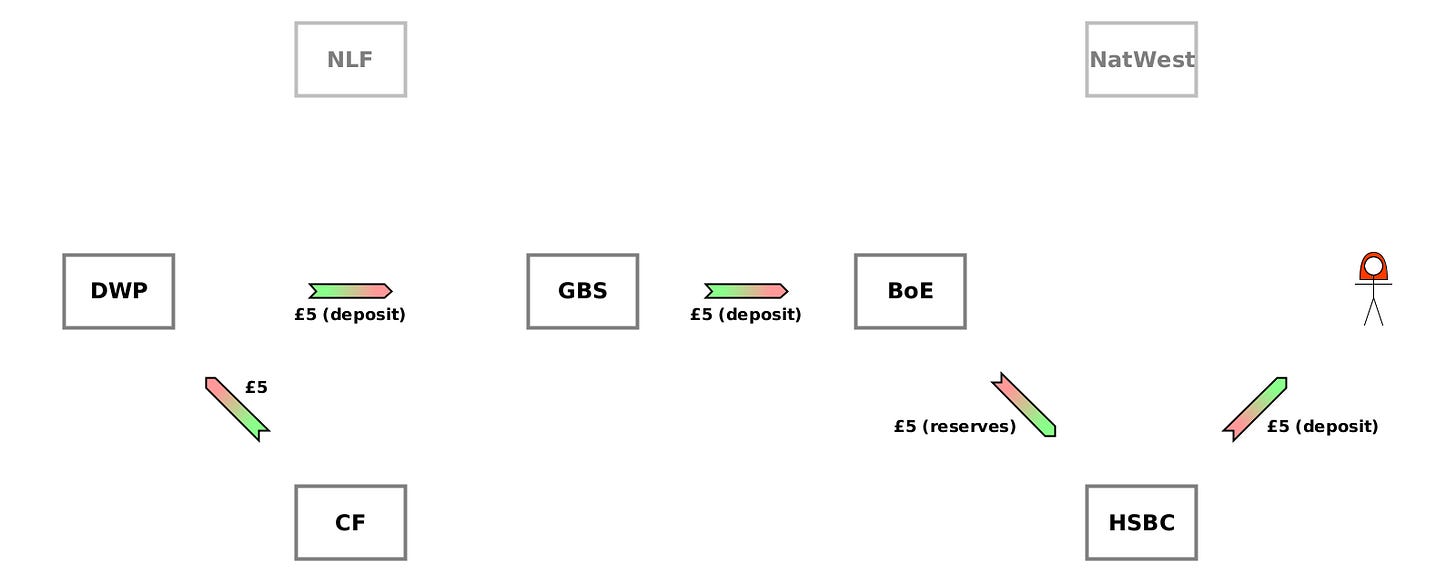

How much everyone’s raw net worth2 changes in each step, and in the scenario as a whole. (Arrows pointing towards someone show their RNW↑ and arrows pointing away from them show their RNW↓). Notice how few of the steps involve anyone’s RNW changing.

How government spending means that the National Loans Fund (NLF) is left with a negative balance at the Bank of England (BoE) after the end-of-day sweep3, but the Consolidated Fund (CF) writes it an IOU to compensate, so it’s actually the CF whose RNW↓ over the whole scenario.

As always, I’ll be cross-referencing the BTW study by putting section numbers in square brackets.

Unfortunately this article’s too long to fit in an email, so please follow the link (click on the article title) to see the whole article.

As we’ve seen before, there are several inconsistencies in the BTW study between the balance sheets and the journals. The journals assume there is always money in the CF’s account at the BoE, but the balance sheets start with an empty account. In this article, I’ll be following what the balance sheets say, because we’re thinking about how the government could spend even without receiving taxes or issuing bonds.

Basics of Exchequer Spending (ctd) [5]

The simplest model of Exchequer spending [5.4]

Step 1 — supply funding, cash issuance

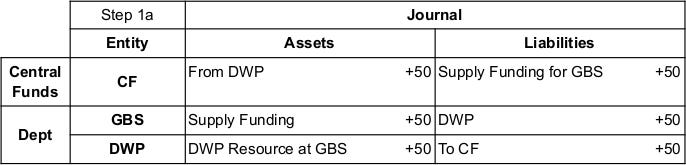

In step 1a,

CF promises to make £50 available to the Government Banking Service (GBS) for settling payments.

GBS creates a £50 deposit for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).

DWP promises to pay the £50 to CF if for some reason it doesn’t end up spending it for the approved purpose.

This is the usual transfer of RNW around a loop: CF→GBS→DWP→CF.

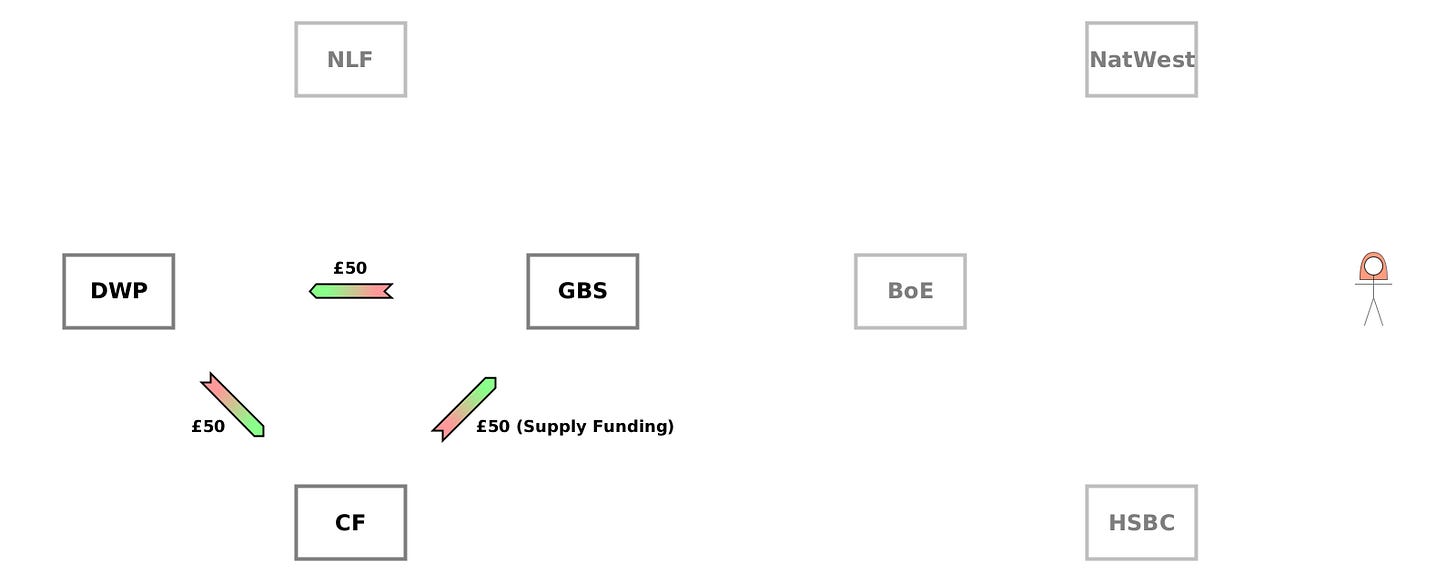

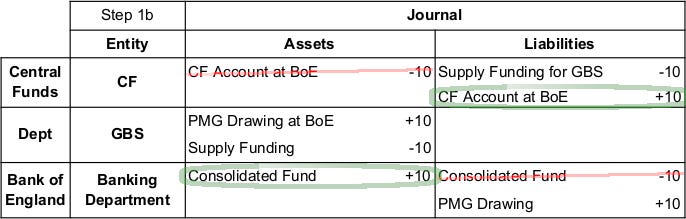

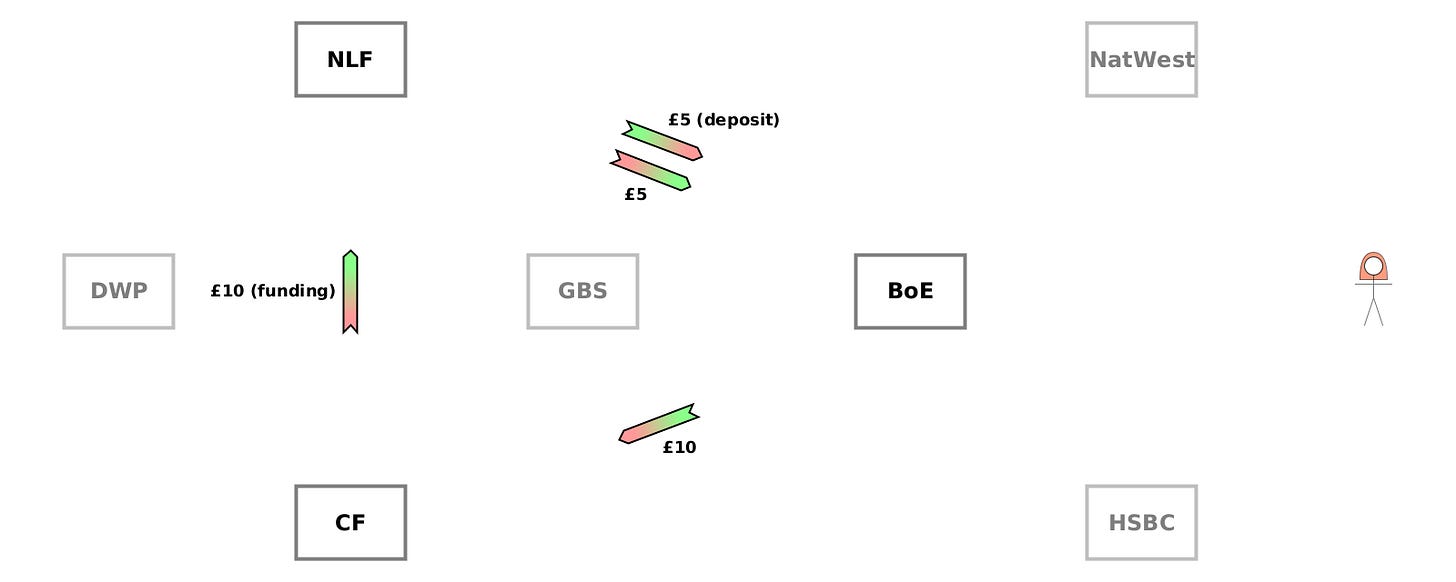

In step 1b, “cash issuance”:

GBS draws down £10 of the £50 of supply funding from CF, in the expectation of DWP spending it in the near future.

CF obtains this £10 by borrowing it from the BoE because it didn’t have any to start with.

I’ve modified the journal for step 1b below to match the balance sheets. Instead of CF writing off £10 already in its account at the BoE (CF A↓, BoE L↓), it instead promises to pay the BoE £10 later (CF L↑, BoE A↑).

This is another transfer of RNW around a loop: CF→BoE→GBS→CF.

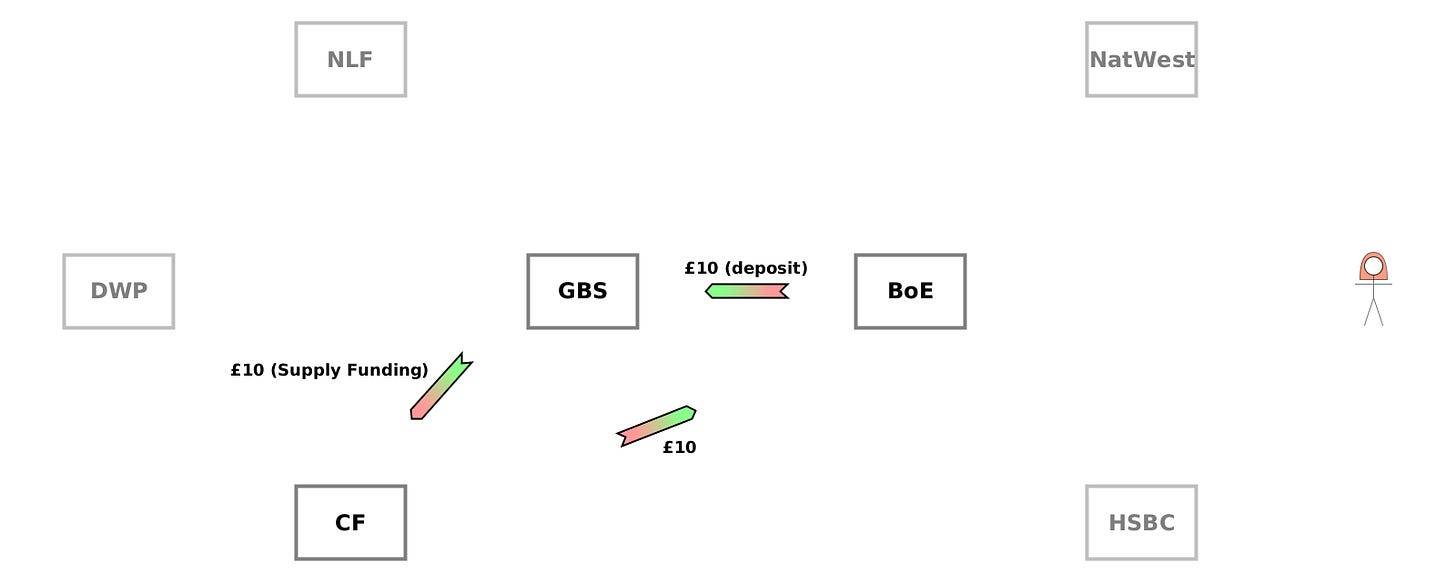

Step 2 — DWP spending

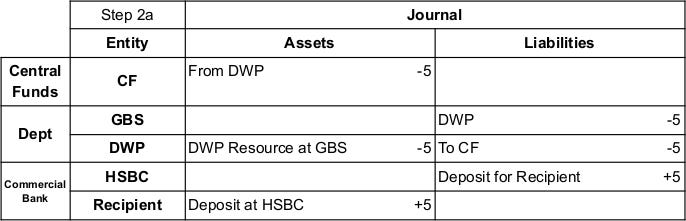

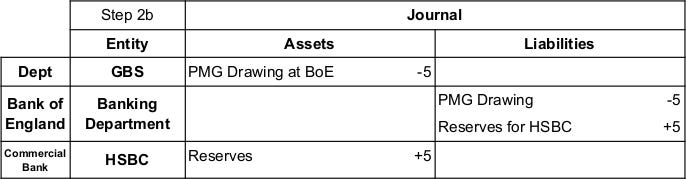

The BTW study slightly simplifies how it shows the DWP’s payment to Alice at this point, by missing out the temporary step of GBS first promising to pay HSBC (Alice’s bank), and settling it later. Step 2 shows the transfer between accounts at the BoE as happening immediately.

Steps 2a and 2b are combined below, since they’re logically a single transaction.

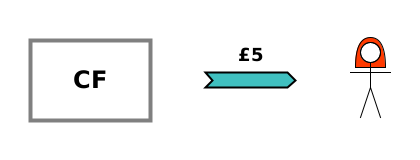

This is a chain of transfers of RNW: CF→DWP→GBS→BoE→HSBC→Alice. CF’s RNW↓ by £5, while Alice’s RNW↑ by £5.

Step 3 — balance sheets

Step 3 of the BTW study just shows everyone’s balance sheet at this intermediate stage.

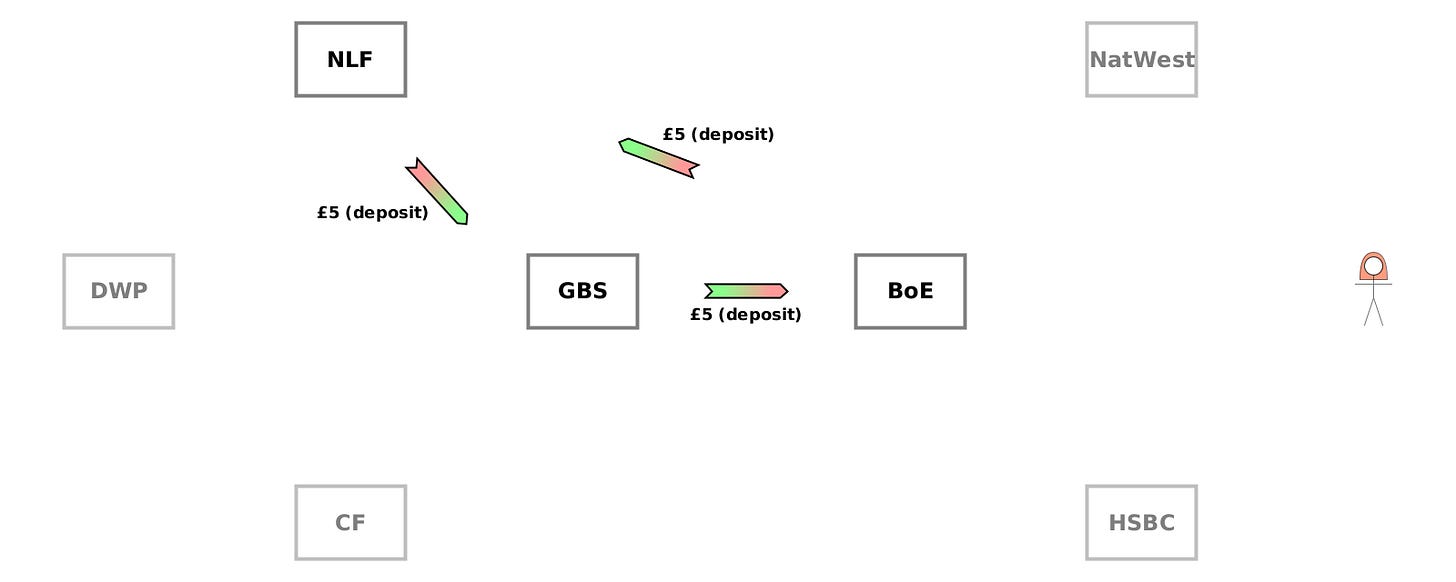

Step 4 — end of day sweep

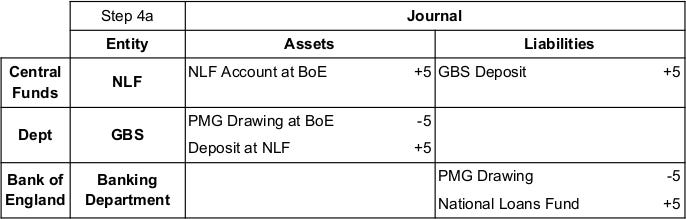

In step 4a, GBS lends its remaining £5 to the NLF overnight.

This is another transfer of RNW around a loop: GBS→BoE→NLF→GBS.

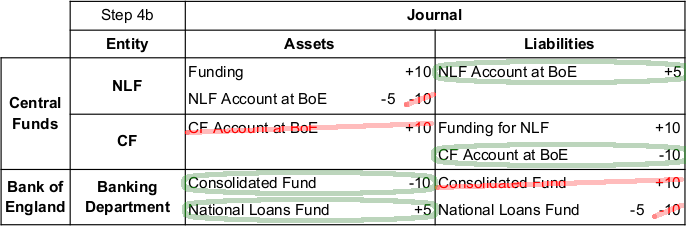

In step 4b, the CF’s debt to the BoE is transferred to the NLF. But the BTW study explains that the CF has to compensate the NLF by writing it an IOU (“Funding”) directly.4

I’ve modified the journal for step 4b below to match the balance sheets. Instead of CF gaining £10 of assets in its account at the BoE (CF A↑, BoE L↑), here the BoE agrees that CF no longer owes the £10 debt from earlier (CF L↓, BoE A↓). Also, since the NLF only has £5 in its account (transferred from GBS), it can’t lose £10 of assets from this account. Instead, it loses the £5 asset and also gains a new £5 liability.

Despite the transfer of £10 from NLF to BoE being split into two different actions, this is still just another transfer of RNW around a loop: NLF→BoE→CF→NLF.

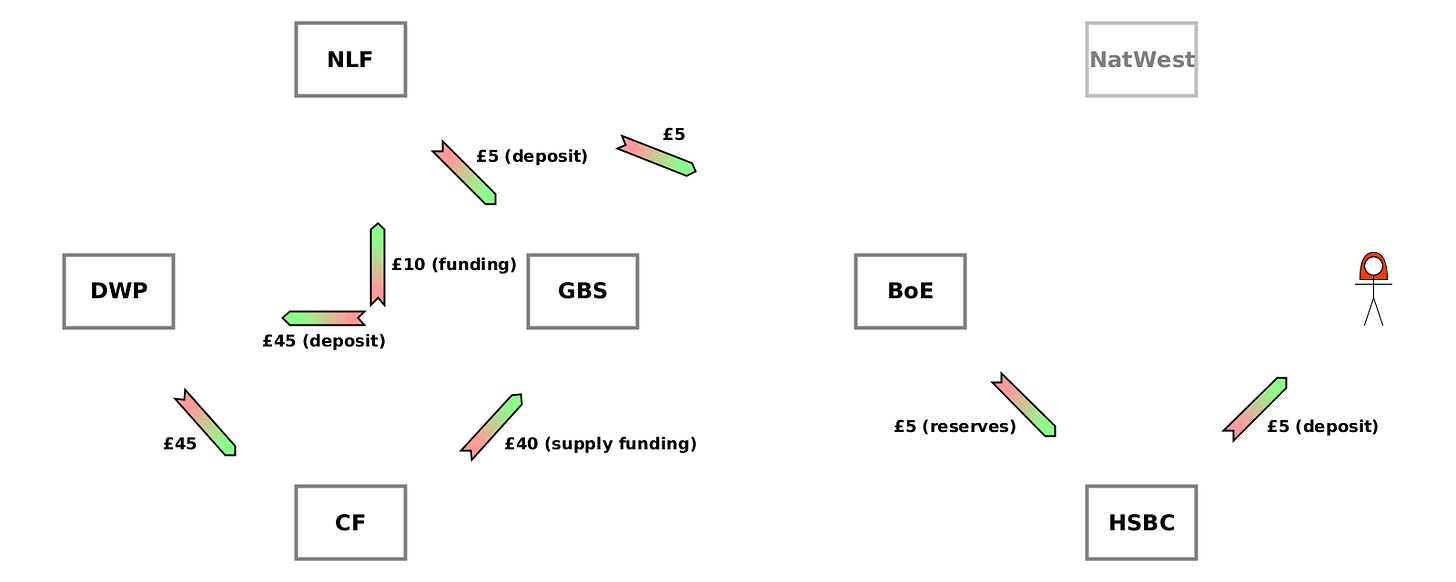

Steps 1-4

As with other scenarios, several of the actions undo all or part of previous actions. Here’s what’s left over when we look at the scenario as a whole:

If you’re wondering what’s happening in the middle of the group of boxes on the left (NLF, DWP, GBS and CF), there’s a £10 transfer from CF to NLF (“funding”), and a £45 transfer from GBS to DWP (“deposit”). I’ve just separated the arrows to stop them overlapping each other.

Go through the boxes, one at a time, and check the total of the arrows pointing towards them and the total of the arrows pointing away from them. For example, there is one arrow pointing towards NLF (£10 from CF), and two arrows pointing away from it (£5 to GBS and £5 to BoE, so the total is also £10). See which boxes have different totals for the arrows pointing towards and away from them.

You should find that the only ones whose RNW changes are CF (↓£5) and Alice (↑£5). In other words, from the perspective of RNW, all that’s happened is that CF has transferred £5 of its RNW to Alice.

Summary

If the government doesn’t have money in its account, the Consolidated Fund (CF) can simply borrow from the Bank of England (BoE) and the government can spend that. At the end of the day, CF’s liability to the BoE is transferred to the National Loans Fund (NLF), but CF is ultimately responsible for it: it writes a corresponding IOU to the NLF.

Government spending involves a lot of accounting activity. There are good reasons for this, notably so that it can keep track of how much spending has been approved by Parliament, and how much of that still hasn’t been spent. But when we look just at how everyone’s RNW changes, almost all of this activity doesn’t have any effect, and the spending itself is simply a transfer of some of the CF’s RNW to the recipient, just like we’d expect from our intuition.

This is where the balances in all of the government’s accounts at the Bank of England are transferred to the National Loans Fund’s account at the end of the day, and typically restored the following morning.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe (i.e. their assets minus their liabilities). In general it is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them. (But in the BTW study, it’s typically just monetary units being added and subtracted). If the idea is new to you, this article explains it with examples.

When there’s no tax income or government borrowing.

A good way to think of this is that there’s an equity relationship between the NLF and the CF. It’s a bit like the CF being the sole shareholder of the NLF, except that the NLF can have negative equity, in which case the CF’s RNW↓.