Understanding Tariffs

A topical post

With tariffs in the news, now seems like a good time to see what the One Lesson1 tells us about them.

A tariff is a tax which a government imposes on imports from certain other countries. If a product arrives from one of those countries, the government charges the importer a percentage of the price of the product. Let’s compare importing a car before and after the government imposes a tariff.

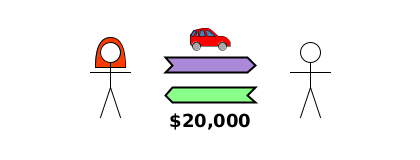

Without the tariff, if Bob is in the USA, and pays Alice’s firm in China $20,000 for a car, Bob would pay the firm $20,000, and Alice’s firm would put the car on a ship and send it across the Pacific to be delivered to Bob. Simple.

Now suppose the USA imposes a 104% tariff on imports from China. With the tariff, the government charges the importer of the car 104% of what they paid for it. In this case, it charges Bob $20,800. So if Bob still wants to buy the exact same car, he would have to spend $40,800: $20,000 goes to Alice’s firm and $20,800 goes to the US federal government.

(The diagram shows Bob owing a new debt of $20,800 to the government. That can be settled with a payment later. I’m honestly not sure whether the payment has to be made before Bob can receive the car — if you do, please let me know. But what’s most important is that $20,800 of Bob’s RNW is transferred to the government).

Obviously, the tariff gives Bob a disincentive to buy a car from China. But exactly what happens next isn’t something I can tell you, and I suspect that most people who claim they know are really just speculating. I’m no expert, but here are a few obvious possibilities:

People in the USA continue to import from China, paying far more for the same goods. (The tariff is a transfer of raw net worth from US consumers to the federal government, not to someone in another country, so the USA as a whole doesn’t lose from this).

US importers and/or Chinese exporters accept a much lower price for themselves, so that the consumer ends up paying the same as before.

People in the USA buy goods from existing firms in the USA which, even though they were more expensive than the Chinese sellers before the tariffs, are now significantly cheaper. These US firms could increase their production, perhaps with some increase in employment.

Entrepreneurs decide to use the opportunity to set up firms in the USA which can sell goods without tariffs. They are protected against competition from Chinese firms which were selling goods at a price lower than a US firm could afford. There could be significant increases in employment.

Consumers simply buy less.

A global trade war ensues, with governments protecting their own countries’ firms from competition by imposing tariffs on imports. Every country tries to produce for its own needs, and perhaps economies of scale are lost. For a time, countries without the capacity to produce what they used to import could end up with either not being able to have certain specialised goods, having inferior quality goods, or having to continue to import. (You can imagine certain well-connected importers getting subsidies from the government to offset the tariffs, while other importers still have to pay the full amount).

I recently saw Jim Rickards, a prominent economic commentator, saying that tariffs won’t affect US consumers, and that number 2 from the list above would be the result. His reason was that consumers can’t afford higher prices, since if they could, shops would have already increased prices before new tariffs were imposed. I don’t find this argument convincing. It seems to ignore possibility number 5 from the list — that consumers simply buy less. After all, there’s no particular reason to assume that the producers and importers can afford to accept a much lower price for their goods.

Do you have any thoughts on which of these is most likely? Let me know in the comments!

The One Lesson of this blog is this:

To understand economics, look at how each decision or action affects each person’s Raw Net Worth (RNW).

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe (i.e. their assets minus their liabilities). It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them. If the idea is new to you, this article explains it with examples.

Wouldn't mind seeing the ledger on an import tariff prior to all this as I'm curious who pays when and what to expect now.

And knowing car dealers buy vehicles prior to selling them, seems like the business fronts up the cash first. And mostly done on credit btw...

Though we are starting to have the manufacturer be the primary seller as here in Australia, is this the same in America? So a external entity would have to pay the tariff, would this come from Eurodollar accounts?

Also, what happens to the tariff paid? Is it like taxes and are deleted or do they go to consolidated revenue?

Jim Rickards has a point that there will be pressure on importers and exporters to take a hit to their margins, and not pass on the full tariff to the consumer. There will also be pressure on producers to build factories in the U.S. to avoid tariffs altogether. And to the extent that prices rise, there will be pressure on consumers to buy less. The outcome of all these various forces is, as you observe, indeterminate.

Empirically, tariffs during Tump 1 did not cause prices to rise & inflation stayed at 1.9%. A recent MIT study estimates that a 20% tariff on China will lead to a price increase in the U.S. of just 0.7%. So, the panic over tariffs causing a recession is probably overdone. Global liquidity is the bigger factor (and it's looking positive for the rest of the year) and if Trump announces a deal with China (which both sides need) then the markets are back off to the races.

Where I think Trump's team may come undone is automation - sure, factories will be built in the U.S. but they will employ robots rather than people.