Can You Spend Your Income?

Stocks v Flows

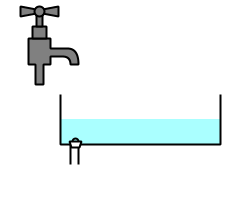

Imagine you have a half-full bath — with the plug in.

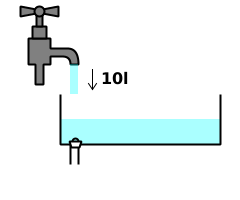

Then you turn on the tap long enough to put in another 10 litres of water.

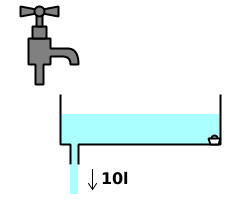

Can you drain out the same 10 litres of water which you just put in?

You can certainly drain out 10 litres of water. But is it the same 10 litres? And does it actually matter?

How banks pay employees

The reason I’m bringing this up is that I’ve been trying to understand how people I’ve been debating against think. A question which has come up a few times is whether banks create money when they pay an employee’s wages.

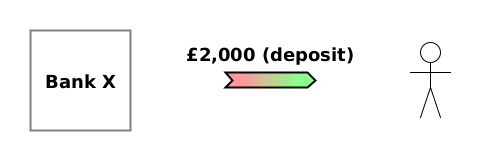

I’d say the answer’s clear. Yes, a bank (usually) pays an employee simply by increasing the balance in the employee’s bank account. The bank is creating a new debt (which it calls a “deposit”), owed to the employee:

As we can see from the arrow, the bank’s Raw Net Worth1 (RNW) ↓ (it owes more) and the recipient’s RNW ↑ (they’re owed more).

I don’t know why anyone would find this controversial. Everyone surely must agree that a bank could pay an employee by handing over some of its cash, and that the employee could then deposit that cash back at the same bank, like this:

There are 3 actions:

(Transaction 1) The bank transfers £2,000 cash to the employee (“transfer debt asset” action).

(Transaction 2, action 1) The employee transfers £2,000 cash to the bank (“transfer debt asset” action).

(Transaction 2, action 2) The bank creates a £2,000 deposit for the employee (“create debt” action).

So cash is transferred from the bank to the employee and back again, and the bank creates a “deposit” for the employee. If the bank and the employee are happy to skip the there-and-back-again cash transfer (actions 1 and 2), why not have the bank simply create the deposit? The result is exactly the same.

But many economists believe that banks only create money when they lend, and most seem to be extremely resistant to having this idea challenged by examples like this. I don’t know why. (If anyone has any suggestions for possible reasons, please leave them in the comments).

One idea which I’ve heard several times is that a bank doesn’t pay employees by creating new money, but by spending some of its earlier revenue. (“Revenue” is often used interchangeably with “income”). Do you see where I’m going with this article?

Flow → flow? Or flow → stock → flow?

Economist Michael Kalecki apparently quipped that “economics is the science of confusing stocks with flows”.

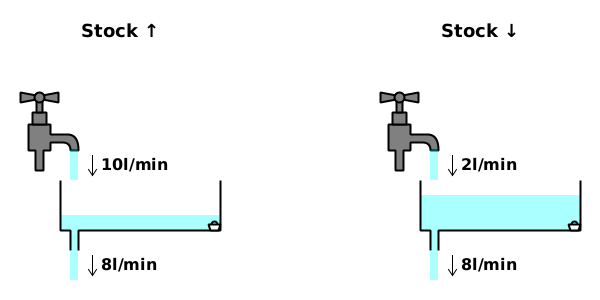

A stock is a value which exists at a point in time e.g. the amount of water in a bath.

A flow is a change in a stock over a period of time. An increase in a stock is an inflow e.g. water running into a bath. A decrease in a stock is an outflow e.g. water draining from a bath.

RNW is a stock. Revenue is an inflow of RNW. Expenses, like wage payments, are an outflow of RNW.

To say that wages are paid from revenues is like saying that the water going down the drain comes from the tap, as though the outflow is directly connected to the inflow. This isn’t too bad a simplification if the total outflows are always exactly equal to the total inflows, but that’s assuming a very unrealistic equilibrium. In reality, outflows are rarely equal to inflows, and the difference between them causes the amount of water in the bath (or the bank’s RNW2) to increase or decrease.

Thinking of the bank as being like the bath, we can say that revenue adds to its stock of RNW. (This often involves destroying existing deposits). And its expenses, like wages, decrease its stock of RNW. (This generally creates new deposits). This seems to me to directly represent what actually happens3. Different sources of revenue (as well as injections of capital) flow into the bank, where they are pooled. And different expenditures flow out of this pool. All of this activity is happening at different times, meaning that the bank’s RNW is constantly increasing or decreasing.

In conclusion, I think it’s most accurate to say that a bank pays an employee simply by creating money: the bank creates a new “deposit” debt (by increasing the balance in the employee’s account), which transfers some of its stock of RNW to the employee. The source (or rather the many and varied sources) of its RNW (and what effect that had on the stock of money) really doesn’t matter when we’re just thinking about what happens when the employee is paid.

It’s not really about the money anyway

Sometimes this sort of argument seems a little futile, because the One Lesson argues that the quantity of money is actually far less important than most people think. It’s RNW which really matters. Creating more money is easy, as we’ve seen many times: a bank can just swap new debts with a borrower. What’s difficult to increase is RNW — to do that, someone has to produce more than they consume in the process.

But I think the discussion needs to be had because so many economists believe that money represents purchasing power. By encouraging economists to understand exactly when money is created, and when it’s destroyed — and importantly, that these are just transfers of RNW — I hope they’ll eventually recognise that RNW is purchasing power, and therefore that Jean-Baptiste Say was right. I’m firmly convinced that a stable and prosperous civilisation depends on this.

Summary

Many economists seem to think of economic activity only in terms of flows. But it’s much clearer to understand exactly what’s happening when you also consider stocks: inflows tend to increase a stock, and outflows tend to run it down. The net effect depends on whether the inflow or outflow is greater (which may be constantly changing over time).

In the One Lesson, the main flows are the economic actions, and the main stocks are each person’s Raw Net Worth (composed of their assets and liabilities).

It’s fine to say informally that someone is spending their income. But it’s clearer to recognise that their RNW sits between their income and their spending, like a bath sits between the inflow from the tap and the outflow from the drain.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe (i.e. their assets minus their liabilities). In general it is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them. If the idea is new to you, this article explains it with examples.

Technically, its equity is increasing or decreasing, rather than its RNW. See the article about equity vs net worth.

The bank probably has a temporary accounting entry for wages owed to employees which haven’t been paid yet. When the deposit is created on payday, the temporary debt would be written off, leaving just the creation of the deposit as the only economic action.

![[1] (TD) Bank X→Bob {£2,000 (cash)} [2] (TD) Bob→Bank X {£2,000 (cash)} [2] (CD) Bank X→Bob {£2,000 (deposit)} [1] (TD) Bank X→Bob {£2,000 (cash)} [2] (TD) Bob→Bank X {£2,000 (cash)} [2] (CD) Bank X→Bob {£2,000 (deposit)}](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6Zkl!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9846759d-16d8-4468-b372-499ab72360ea_480x240.png)

Does not Ravel handle this correctly. According to

https://www.patreon.com/file?h=107942051&m=328188559

The sum of equity flows must be zero - a conservation law. However I dont believe that they are implying that the sum of equity stocks is zero.