Government Finance (2)

Is "fiat" currency a free lunch?

Last time I wrote about Professor Steve Keen’s analysis of where money comes from — both private bank money (“deposits”) and central bank money (cash or “reserves”). The argument he’s making in the process is that excessive private sector debt is a problem, but government debt isn’t:

This attitude towards government debt and deficits—that government debt should be minimised, that deficits are undesirable, that interest payments on government debt are a punitive impost on future generations, and that high debt and high interest payments can even lead to a government going bankrupt—are key facets of contemporary politics.

And they are all completely wrong, as is easily shown by looking at the accounting of the mixed credit-fiat monetary system in which we live.

— Steve Keen

He goes on to show exactly how both private bank and central bank money creation work, as well as the issuing of government bonds. And I agree with his analysis of how the assets and liabilities of the different entities change. I particularly like that he separates out the central bank from the government, which is a clearer and more intuitive than the approach of MMT, which treats the central bank as a part of the government.

But where I disagree in the real-world interpretation of whether excessive government debt is a problem: it seems clear to me that it’s just as much a problem as excessive private sector debt. This is my first attempt to put this reasoning into a single place, so I’d appreciate any feedback on the arguments I use. I’m sure they can be refined.

Something for nothing?

Keen, like the MMT community, says that a government debt is the savings of the private sector.

since a Deficit adds to the Assets of the Non-bank Private Sector, without creating an offsetting Liability, as is the case with a bank loan, a Deficit increases the net worth—the Equity—of the Non-Bank Private Sector. Far from borrowing money from the private sector, as Neoclassical economists claim, the Deficit creates both money and net financial worth for the private sector.

— Steve Keen

The whole impression is that government creates something of value for the private sector by fiat1, and that the outcome is completely positive.

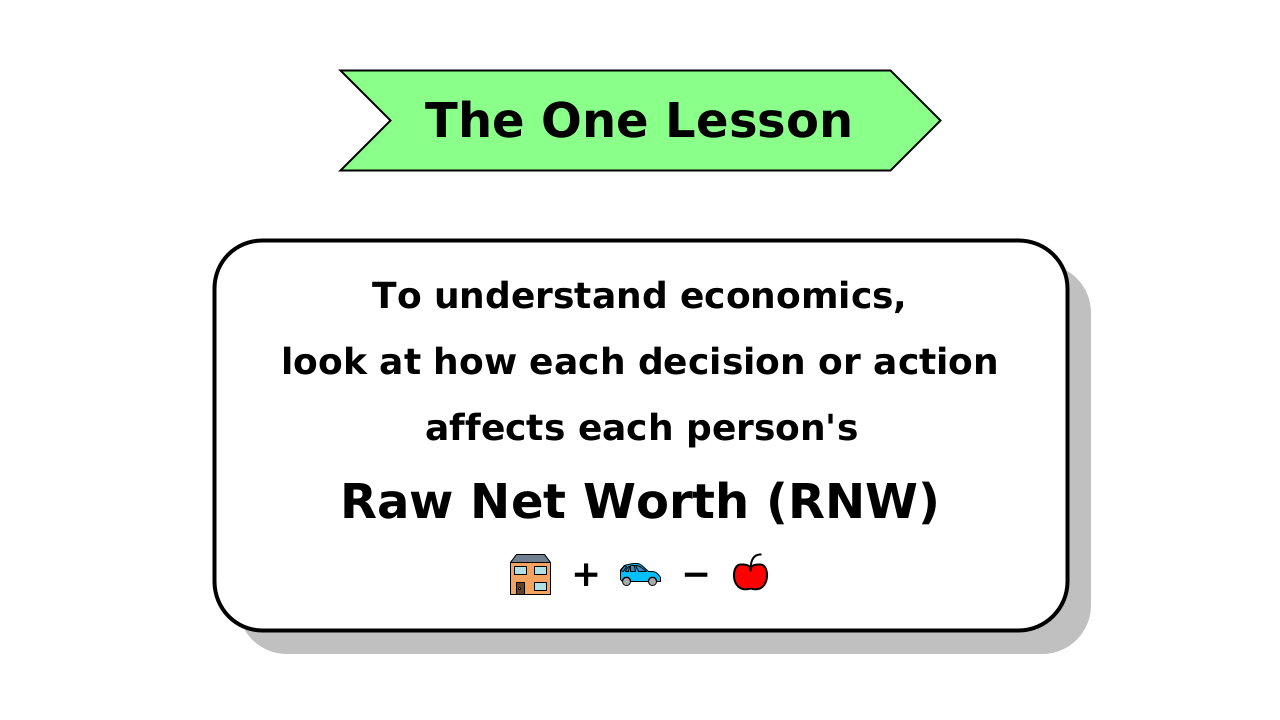

But if you’ve been following this blog for a while, you’ll probably be aware that, apart from production and consumption, economic activity is a zero-sum game: every arrow which points to someone (increasing their raw net worth2) also points away from someone else (decreasing their RNW by exactly the same amount). Only production can increase someone’s RNW without decreasing someone else’s.

Since government spending isn’t producing or consuming anything, the One Lesson (see below) tells us that there’s no free lunch here. Government spending is at best a transfer of RNW, not the creation of wealth.

Keen and the MMT community agree that the government is accumulating liabilities, but effectively (or even explicitly) argue that this isn’t really negative in the way that the assets accumulated by the private sector are positive. Between them, the main arguments they use are3:

A government has lots of valuable assets (land, buildings, warships, etc.), so there’s never any danger of its liabilities getting high enough to make it insolvent.

A government which owns a central bank can never run out of money, so it can always pay its debts.

A government has military force which backs its currency.

Let’s look at each in turn.

Government has lots of assets

What backs the government […] is what you’re talking about here: non-financial assets. And you don’t need to sell them — they just have to exist.

— Steve Keen

A government certainly has a lot of assets under its control: land, buildings, infrastructure (e.g. roads), government-run businesses, warships, etc. Does that mean there’s no downside to the government accumulating liabilities?

The One Lesson approach tells us there is a clear downside: its RNW decreases. Remember from the macroeconomics series that the economy is all about the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services: the real economy. Debts are extremely important, but their effect is only to make the real economy work more efficiently, allowing trades to take place which otherwise couldn’t.

So the important question to ask is whether the private sector is getting any benefit in the real economy from being owed debts by the government. And there’s only one way this could happen: the government does sell some of its assets. This is what privatisation is. In the 1980s, the UK government sold lots of government-owned infrastructure firms (gas, electricity, telecoms) to people in the private sector, in exchange for them writing off some of the national debt. It doesn’t matter to what extent you agree with the policy of privatisation: what can be said for certain is that the accumulated liabilities of the government led to the government transferring control of a number of assets to the private sector.

Even if the government starts with a huge number of assets, accumulating more liabilities with the intention of settling them will eventually deplete the assets. You can compare it to filling a bath tub with water from a reservoir: someone gets to have a bath, which makes an obvious impact on them without any obvious impact on the level of water in the reservoir. But there’s no doubt that the amount of water in the reservoir is reduced by as much as is taken. You’re just gradually depleting a huge accumulated resource.

The only alternatives to privatisation are:

Cancel the debt

Take something from someone else (or even from the creditor), and use that to settle the debt to the creditor, or

Leave the debt outstanding forever.

Options 1 and 2 are both forms of taxation: transferring wealth from the private sector to the government. Option 3 is indistinguishable in practice from cancelling the debt.

In summary, it doesn’t matter how many resources the government starts with. Any time it accumulates a liability, it either depletes its RNW by that amount, it simply takes from someone in the private sector in order to pay the debt, or it just treats the debt as though it doesn’t exist.

Government owns the central bank

Many MMTers argue that, because the government can order the central bank to create limitless money for it to spend one way or another, it can never be insolvent. This, they argue, means that it can make as many promises as it likes, and it can always keep them.

What does the One Lesson tell us?

When a government orders the central bank to create some money for it, it swaps IOUs with the central bank (either immediately, or via an indirect route). If it then spends some of this money to pay its existing debts, it’s not reducing its total debt at all. It’s just replacing one debt with another.

The ability to pay debts whenever it wants by writing new IOUs doesn’t prevent it from being insolvent. It prevents it from being illiquid. That is, it can always pay its debts which are due now, but unless it gets some sort of income (generally from taxation) it is only replacing one debt with another, which doesn’t solve its debt problem at all.

Government owns the military

Some people say that a currency is backed by the military forces of whichever authority issues the currency.

So if you’ve got a non-financial asset called the United States Navy and Air Force and Army, I think that might validate the American dollar within its own territory, and unfortunately a large part outside as well.

— Steve Keen

But what does this really mean economically? It surely doesn’t mean that creditors of the government can obtain guns and bullets, or tanks and warships as settlement of the debts owed to them.

The only relevance I can see to this argument is that a debtor’s control of military force makes it hard for creditors to demand payment, allowing the debtor to defer payment of its debts forever, which is indistinguishable from cancelling them.

Summary

When a government becomes indebted to the private sector, its RNW decreases and the private sector’s RNW increases. But RNW reflects what people will end up with if all debts are paid, which involves either privatising assets under its control or imposing a tax on the private sector to pay for it. If it has no intention of ever paying its debts, and the creditors have no way to force the government to pay, you can say that the government doesn’t have a debt problem, but equally you have to recognise that the private sector has a “some of our assets are in the form of debts owed to us by someone who’s never going to pay” problem. The creditors are effectively paying tax equal to the amount owed to them.

There really is no free lunch. That’s not at all to say that the government shouldn’t ever get into debt, or shouldn’t issue a national currency. We can discuss the pros and cons of these ideas. But the idea that government deficit spending creates wealth for the private sector, rather than simply transferring it from somewhere, is simply wrong. Production is the only way to increase one person’s wealth without decreasing someone else’s by the same amount.

“By fiat” means that it happens simply by someone speaking.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe. It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them.

This is my recollection of the main arguments I’ve seen. Please let me know in the comments if you find other arguments they make which I haven’t addressed.

"Since government spending isn’t producing or consuming anything, the One Lesson (see below) tells us that there’s no free lunch here."

I hope you are not saying governments don't produce anything. When the government spends, it may not make apples appear by magic, but it does produce MONEY. It also causes a whole chain of real production to take place. As the currency sovereign, the government's financial net worth is effectively infinity - so infinity minus something equals infinity. However the economy it owns and manages does have a limited productive capacity to make apples appear.

If apples can appear from nowhere and we call that "production" then it is even easier for something notional, such as money, to pop into existence.

You do not mention how money gets a value. It is in demand to pay taxes. Taxation makes fiat money valuable.

On judgement day, when nobody needs any money to make an economy work, the government can tax all its money back and pay out all its liabilities. What's the problem?

On a second reading, I now think we do have some things in common. I do not like the government paying interest on reserves or on bonds. This is because it is a subsidy for the wealthy. The problem discussed above is less concerned about the monetary sovereign's ability to create money and has much more to do with the issuing of debt - converting reserves into bonds - accepting liability for private sector savings - and worse, paying the private sector interest on the money which the government created.

Issuing bonds is something which governments do "voluntarily", by which I mean I am not at all convinced that "issuing government debt" or "accepting deposits", is a necessary function of a monetary sovereign unless the banking system is entirely public. A continuously accumulating liability that enriches the private sector according to how much money the have already, means that taxation has to be higher in order to control inflation.

In favour of issuing bonds:-

providing the safest investment vehicle for savings has a stabilising effect on the financial sector. Not only does it provide control of interest rates, but it also reduces the amount of savings that would otherwise be forced into asset bubble speculation. By encouraging long term savings, cash is temporarily removed from circulation, so part of today's inflation problems can be shifted to the future. I am sure there are more effective ways to adjust the money supply, but they tend not to make people feel good about voluntarily limiting their consumption spending. I am not so confident about the benefits of time shifting spending because it is possible that bonds are readily convertible into cash at any time. I'm no expert here.