Income (4)

Services and income

This week we’ll look at how services affect people’s incomes. If we remember that services are the simultaneous production, transfer and consumption of an immaterial product, we’ll see that it’s really no different from goods.

Nearly 2 years ago (!) I wrote an article on services, where I showed that Jean-Baptiste Say explained services as the simultaneous production, transfer and consumption of an immaterial product (e.g. medical advice or a musical performance).

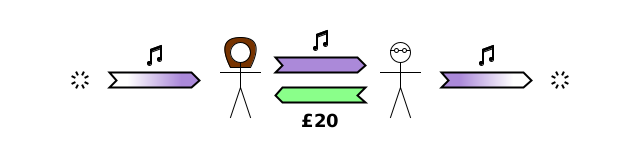

Charlotte’s putting in the effort to produce the music (by singing), and Dom is receiving the benefit of consuming it (by listening to it). What does this do to each person’s raw income?

Raw income from a service

In the last article on income, I wrote that the only coherent definition of income which I could find was:

Someone’s (raw) income is the change in their raw net worth1 resulting from any action apart from unproductive consumption.

So we work out someone’s raw income by adding the arrows pointing to them, and subtracting the arrows pointing away from them except for unproductive consumption. Dom’s just listening for enjoyment, not as part of the process of producing something, so the arrow pointing away from him is unproductive consumption. Check the arrows in the diagram above, and see if you agree with this:

Charlotte produced a service, but gave it away for free, so she has no income from it. Dom received the service, so the performance was income for him, even though he consumed it immediately.

Let’s see how this changes if Dom pays Charlotte £20 to hear her performance:

The only difference is that the £20 payment is negative raw income for Dom, and (positive) raw income for Charlotte. So in total, each person’s raw income is:

Notice that the total raw income is still the same. Charlotte earned £20 of income for her performance, and Dom gave up £20 of income to obtain the performance as income.

Raw income from reproductive consumption of a service

Some services are consumed as part of producing another product. One example might be a taxi driver getting their car windows washed so they can continue to provide a taxi service. (It’s hard to do that if the driver can’t see out!)

Here, Frank is a taxi driver, and Bob is charging him £10 to wash his car windows.

Unlike Dom listening to music, Frank’s consumption of the service is reproductive, so it counts towards income. Here’s each person’s raw income:

Bob’s received an income of £10 for his work, and Frank has a negative income of £10, but it’s a necessary part of providing the taxi service from which he earns his income. You can think of washing the taxi’s windows as part of the supply chain for the taxi service. It’s ultimately paid for by the users of the taxi service.

Summary

Jean-Baptiste Say’s explanation that services are the simultaneous production, transfer and consumption of an immaterial product makes it easy to understand their role in the economy. Income for services works in exactly the same way as income for goods:

Producing a service is income for the provider, but if the service is provided for someone else, the negative income from transferring the service cancels it out, leaving no net income.

Receiving a service is income for the recipient. If it’s consumed reproductively, the consumption is negative income, which cancels out the income, leaving the recipient with no net income. But if it’s consumed unproductively, the consumption has no effect on the recipient’s income, so overall the service was income for them.

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe (i.e. their assets minus their liabilities). It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them. If the idea is new to you, this article explains it with examples.