Income (3)

An actually useful and coherent definition

Now we’ve seen what’s meant by reproductive and unproductive consumption, we’re ready for a definition of income which works for all situations. Armed with that, we can go back to the questions in the first article of this series on income, and see what answers it gives us.

The definition I’ve been led to is probably a bit different from what you’ve seen before, but I’m convinced it’s the only truly useful and coherent definition. It’s also pretty simple. Here it is:

Someone’s (raw) income is the change in their raw net worth1 resulting from any action apart from unproductive consumption.

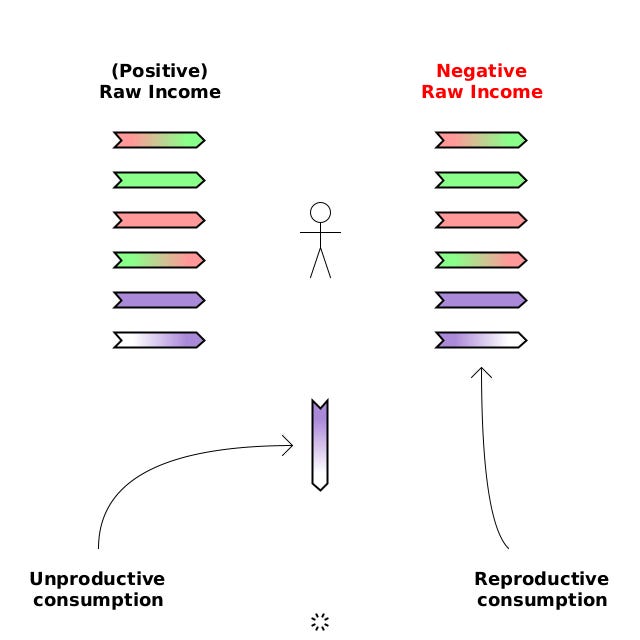

That’s it! Here’s an illustration of it:

To summarise the diagram:

All actions pointing towards someone, including production, are (positive) raw income.

All actions pointing away from someone, except for unproductive consumption, are negative raw income.

Unproductive consumption isn’t part of raw income.

Answering the earlier questions

So let’s take a look at the original questions from the first article in this series on income:

What exactly do we mean by raw income?

Raw income is the change in someone’s RNW from any action apart from unproductive consumption.

What’s the economic significance of raw income?

Someone’s raw income is what provides them with the ability to consume unproductively (i.e. for the personal benefit it gives them, rather than it being part of the process of producing something else). This ability comes from either:

Consuming a tangible asset which they now own, or

Exchanging some of their RNW for something tangible to consume (either directly or via a series of exchanges).

What units is raw income measured in?

Raw income, as a change in RNW, is measured as a sum of things with different units. For example, someone who in one week produces 100 apples, and sells 10 of them for £1 has a raw income of (90 apples + £1) for that week.

Which events or actions affect someone’s raw income?

All actions apart from unproductive consumption.

Is someone’s raw income always a result of someone else’s spending?

No. For example, when someone produces something, that is a part of their raw income, but nobody spent anything. (See diagram above where Alice’s production of 100 apples is 100 apples of raw income).

Also “spending” implies a transfer of specifically money. Raw income is a more general idea. If Alice gives Bob an apple, this is (positive) raw income for Bob (and negative raw income for Alice).

What, if anything, does raw income mean when we’re looking at Robinson (“Bob”) Crusoe on his desert island, where there’s no money?

It means exactly the same as in any other situation: the change in his RNW from actions apart from unproductive consumption. If he harvests some apples or collects firewood, that is production, and therefore raw income. It gives him the ability to consume unproductively e.g. eating the apples for nutrition, or burning the wood for warmth.

Is it only real people who have raw incomes, or do corporations (e.g. limited companies and governments) have raw incomes too?

Anyone who has a raw net worth has a raw income. This means both real people and corporations, such as limited companies, governments and trusts.

If we add up everyone’s raw income, does that tell us anything interesting?

Yes, it tells us how much was added to the stock of things which can be consumed unproductively.

What about the raw income of someone who is self-employed?

As we saw in the second article of this series, production of a product is raw income for the producer. If they then sell that product for money, receiving the money is (positive) raw income, and handing the product to the buyer is negative raw income (which exactly offsets their raw income from producing it).

If someone borrows money, that lets them buy things now which they otherwise couldn’t have, so is that part of their raw income?

No. When someone borrows, they are committing to repay, so the (positive) raw income of what they receive is offset by the negative raw income of the promise to repay. The only actual raw income from borrowing comes from the interest charged. Here’s an example:

If a bank lends £1,000 to Charlotte, and she agrees to pay it back with 5% interest (i.e. £50), that is £50 of raw income for the bank, and -£50 of raw income for Charlotte. The new “deposit” debt owed by the bank to Charlotte, and the new “loan” debt owed by Charlotte to the bank cancel each other out: one action is £1,000 of raw income and the other action is -£1,000 (i.e. negative) of raw income.

So borrowing doesn’t provide the borrower with raw income. Apart from the interest, there is no (net) raw income from lending.

If a bank simply creates money for an account holder (e.g. if it pays £2,000 wages to its employee, Dom), that is (positive) raw income for the account holder, but also negative raw income for the bank.

If Alice and Bob give each other £1,000, does this increase their raw incomes? If so, doesn’t that make raw income a meaningless value, because they could both increase their raw incomes without limit by doing this over and over again?

It would make raw income meaningless if it were true — but it isn’t. Even though Alice giving Bob £1,000 is (positive) raw income for Bob, it’s negative raw income for Alice.

So if Alice and Bob give each other £1,000, it doesn’t affect their raw incomes because for Alice, one of the two actions is £1,000 of raw income and the other action is -£1,000 of raw income. The same is true for Bob (but the other way round).

In the example in an earlier article where Alice pays Dom £1,000 to harvest wheat for her, if Dom then spends £100 on wheat from Alice, is this part of Alice’s raw income, and if so, is there some double-counting going on because the £100 was already part of Dom’s raw income?

No, there’s no double-counting, because Alice’s £100 of raw income from Dom handing her the money (in transaction 2 below) is -£100 (i.e. negative) of raw income for Dom.

Before Dom spent the £100 (immediately after transaction 1), his raw income was £1,000. After he spent the £100 on 100 bushels of wheat, his raw income for the whole scenario was (£900 + 100 bushels of wheat).

The £100 of raw income for Alice undoes some of the -£1,000 of raw income from when she paid Dom. Supposing the harvest was 2,500 bushels of wheat, her raw income just after paying Dom was (2,500 bushels of wheat - £1,000). After Dom buys some of the wheat, her raw income is (2,400 bushels of wheat - £900).

At every stage of the scenario, their combined raw income is 2,500 bushels of wheat, which (not coincidentally) was the amount produced. Transfers (and therefore exchanges) of any sort have no effect on the combined raw income of the people involved — or of anyone else for that matter.

Summary

Almost all economic actions are (positive) raw income for one person, and negative raw income for another. The only exceptions are:

Unproductive consumption, which isn’t raw income for anyone;

Reproductive consumption, which is negative raw income for one person, but nobody’s positive raw income; and

Production, which is raw income for one person, but nobody’s negative raw income.

The only source of net raw income is production!

Someone’s raw net worth (RNW) is what they own plus what they’re owed minus what they owe (i.e. their assets minus their liabilities). It is a “heterogeneous” sum/difference, which just means that things of different types are added and subtracted, not monetary “values” which have been assigned to them. If the idea is new to you, this article explains it with examples.

![[1] (P) void→Alice {apple ×100} [2] (TT) Alice→Bob {apple ×10}; (TD) Bob→Alice {£1}. Alice's Raw Income = apple ×90 + £1 Bob's Raw Income = apple ×10 - £1 [1] (P) void→Alice {apple ×100} [2] (TT) Alice→Bob {apple ×10}; (TD) Bob→Alice {£1}. Alice's Raw Income = apple ×90 + £1 Bob's Raw Income = apple ×10 - £1](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ylHL!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F71852957-1312-44b0-a3d4-e8365ea08a8c_640x300.png)

![[1] (S) Dom→Alice {harvesting}; (TD) Alice→Dom {£1,000}. [2] (TD) Dom→Alice {£100}; (TT) Alice→Dom {wheat ×100}. [1] (S) Dom→Alice {harvesting}; (TD) Alice→Dom {£1,000}. [2] (TD) Dom→Alice {£100}; (TT) Alice→Dom {wheat ×100}.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!1k0u!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F61b7f5dd-ca9c-470e-8970-e13a0a095375_420x300.png)